By the late 1800s, London had become the financial centre of the world thanks to the expansionist colonisation of the 1700s and industrialist consolidation of the Victorians.

The City of London now had strong links to rapidly expanding bank markets around the world, particularly in the USA where the Industrial Revolution fuelled corporate financing needs.

International banking for corporate clients was dominated by family run merchant banks, who traded on their history and name, such as Rothchilds, Warburgs, Schroders, Kuhn, Loeb, J.P. Morgan, Goldman and Sachs. It is worth noting for example, that there was no obligation for banks to disclose their capital reserves at the time, which is another reason why reputation and name were so important.

Due to the capital requirements of expanding international businesses, it was also the case that no single bank could fund the entire needs of their corporate clients, and so the corporate bond market along with Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) became a critical factor in a bank’s portfolio.

An IPO was difficult for example, as many investors had no idea if the company was worthy of investment. Hence, a successful offering created more trust in a bank’s name, with the bank often demanding positions on the boards of the companies they were working with to raise capital to ensure good governance.

Then war began and the banks roles changed dramatically.

From financing international expansion of businesses, the London banks were now focused upon financing governments and securing assets.

Gold reserves were moved out of the warzone, with much placed in the newly formed New York Federal Reserve.

The New York Fed opened for business on November 16, 1914 and, on its first day of operation, the Bank took in $100 million from 211 banks around the world, many from London. The Bank's vaults, located 86 feet below street level, were built on Manhattan's bedrock and, by 1927, the vault contained 10% of the world's entire store of monetary gold (the Fed’s vault today contains about 22% of the world’s official monetary gold reserves).

Meanwhile, banking was focusing upon supporting the war efforts, as illustrated by the Tank Bank.

The Tank Bank was created by the National War Savings Committee in 1917 to fund more investment in tanks after the Battle of the Somme.

A year later, in November 1917, the Tank Corps won the Battle of Cambrai and a battered tank named ‘Egbert’ was recovered from the battlefield, shipped to London and installed in Trafalgar Square. People were then invited to buy war bonds and certificates, and to queue up outside this unlikely ‘new god’ so that their bonds could be specially stamped by young women seated inside the tank.

Miss Marie Lohr buying a war bond at the tank bank in Trafalgar Square March 1918

After the Great War, prosperity boomed due to easy access to credit.

Of course, a great boom leads naturally to a great crash, and the Great Depression was caused by the policies created just after the Great War.

In particular, one of the main causes for the Great Depression was the political and policy battles between the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve of the United States.

Like the Bank of England until it was nationalised after the Second World War, the Federal Reserve had been, and still is, a privately owned and privately managed institution.

It was created in December, 1913 to avoid further financial busts, like those of 1837, 1873 and 1893.

What it led to was an economic battle with Britain, and its Central Bank Governor Montagu Norman, over gold.

Sir Montagu Norman, the Governor of the Bank of England from 1920-1944, came from a long line of bankers. His grandfather was Sir Mark Wilks Collet, who had himself been Governor of the Bank of England during the 1880s.

During World War I, all the industrialized nations of the world had left the Gold Standard except the United States, which is why the Federal Reserve had attracted so much gold, and Montagu Norman was determined that Britain should return to the Gold Standard.

The challenge he faced was that, by the mid-1920s, two thirds of the world's supply of monetary gold was concentrated in the United States and France. Britain had little gold, a weak economy and a lot of debt from the War.

Montagu Norman knew that a return to the pre-1914 pound rate was much too high for the war-torn British economy to support, as it would make imports cheap but exports impossible, but wanted this level of exchange in order to boost the economy long-term.

He convinced Winston Churchill, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, that it would be good for Britain to return to the gold standard at pre-War rates and, in April 1925, Churchill tied us back to the dollar at this high level of exchange ($4.86 to the £1).

Exactly as predicted, the British economy took a turn for the worse, with industrial exports priced out of the world market and unemployment rising to 1.2 million people, the highest since Britain had become an industrial country and leading to the General Strike of 1926.

Montagu Norman achieved his boost for the economy long-term however, by using this high pound exchange rate for a land grab for Britain.

Britain’s industrial leaders and their financiers set out on a whirlwind expedition of procurements, buying up US and European real estate, banks and firms.

Montagu Norman’s real goal had therefore been to create British financial supremacy: “restoring the City to its coveted place at the heart of the financial and banking universe”. [Andrew Boyle]

A second piece in Montagu Norman's tactics was to encourage Benjamin Strong of the New York Federal Reserve Bank to follow a policy of easy money, low interest rates, reflation, and a weak dollar.

Strong was easily influenced in monetary policy by the reputation of the Bank, and Montagu Norman in particular, and worked closely with him and his European counterparts in trying to encourage post-war support of the European economy.

This led to much of the new credit the Federal Reserve had created flowing into loans to individuals to buy cars - the automobile was the ultimate status symbol of the Roaring Twenties in the USA - whilst the rest went into loans for the margin buying of stocks.

Ultimately, it led to America ending the 1920s in a bubble economy, where easy money was being used by all and the Great Depression bust was still to follow.

However, the bust was triggered by a third and final piece of political jostling between London and New York over interest rates.

Between July 1928 and February 1929, the New York Fed lending rate was 5%, half a point higher than the 4.5% that was the going rate at the Bank of England.

This meant that gold moved to the USA to earn higher interest.

All through the autumn of 1928, the Bank of England haemorrhaged gold to the USA. In order to slow the movement, the Bank raised the London bank rate to 5.5% during the first week of February 1929 but, by late April, the pound began to weaken again.

Things rumbled on in this way until late in 1929 when a bank collapsed: the Clarence Hatry group, worth about £24 million (£400 million today).

Montagu Norman seized this opportunity to restore confidence by raising the Bank of England discount rate one percent to 6.5%, and to try to move investment from America back to Britain.

6.5% was a very high discount rate – it had not been so high since 1921 – and a full point had been a big jump.

Added to the steps already taken by the Bank of England, these actions generated a giant sucking sound as money was pulled out of New York and across the Atlantic.

The impact was massive, particularly as the Fed had encourage a credit bubble with, as mentioned, much of this easy money being used as margin for buying stocks.

On October 29th 1929, known as Black Tuesday, the US stock markets crashed, leading to a complete loss of confidence in the banking system.

The Depression kicked off full force from 1931 onwards, when banks called in the loans they had been giving away, only to find they could not be paid back.

Over 9,000 banks failed during the 1930s and, by April 1933, around $7 billion in deposits had been frozen in failed banks.

However, London largely escaped the ravages of the Great Depression, as the City was being rebuilt thanks to the buying spree given the Pound's high valuation against gold and the reparations of Germany, a nation being punished for its war efforts to the tune of $32 billion – near $500 billion in today’s money.

This punishment also led to the seeds of the Second World War as Hitler’s support emerged in the early 1930s from the depression in Germany and the fall of the Weimar Republic.

In terms of reparations, Lord Keynes compared it to the imposition of slavery on Germany and her defeated allies in his “Economic Consequences of the Peace”. Not surprising as Germany also had a weak economy, but now owed $32 billion backed by gold, and to be repaid over 62 years at an interest rate of 5%.

The reparations issue was complicated further by the inter-allied war debts, with France and Britain now debtors to the United States. For a time a system emerged in which Wall Street made loans to Germany, so that Germany could pay reparations to France, which could then pay war debts to Britain and the USA.

It was a merry-go-round of money, but one based upon interest on loans rather than production, and was therefore doomed.

Interestingly, Montagu Norman was a key financial supporter of Adolf Hitler, during his rise to power in the 1930s.

For example, Montagu worked closely in dealing with the Great War loans with Hjalmar Schacht, Governor of the German Reichsbank and later Finance Minister in governments in which Adolf Hitler was chancellor.

He even put his own reputation on the line in September 1933, to ensure that the Hitler regime was successful in its first attempt to float a loan in London. The Bank of England's consent was at that time indispensable for floating a foreign bond issue, and Norman made sure that the “Hitler bonds” were warmly recommended in the City.

In other words, London was instrumental between the Wars in creative ways to regain market supremacy from economic manipulation against the USA using interest and exchange rates, whilst being part of a European conclave that first ruined Germany and then invested in its rebuilding by supporting the political party that ultimately rallied Germany to war again to overcome such ruin.

In hindsight, you could say that Montagu Norman and the City had a lot ot answer for from back in the day.

But then the post Second World War world saw the City gain even greater prominence and focus, thanks to Bretton Woods, the Big Bang and more.

Meanwhile, for those seriously interested in the role of Montagu Norman and the City in the Great Depression years, this 60-page thesis makes it quite clear how important a role these policies played during the 1920s and beyond.

Much of this entry has been taken directly from this thesis, and it is worth exploring further for those intrigued by financial histories.

This is the eleventh in a series about how the City of London developed its financial prowess and system.

Previous entries include:

- Part One: The Romans

- Part Two: The Vikings

- Part Three: Medieval Times

- Part Four: The Tudors

- Part Five: The Stuarts

- Part Six: The Bank of England

- Part Seven: Lloyd's of London

- Part Eight: The London Stock Exchange

- Part Nine: The 1700s

- Part Ten: The Victorians

- Part Eleven: World Wars

- Part Twelve: After World War II

- Part Thirteen: The Big Bang

- Part Fourteen: Crisis

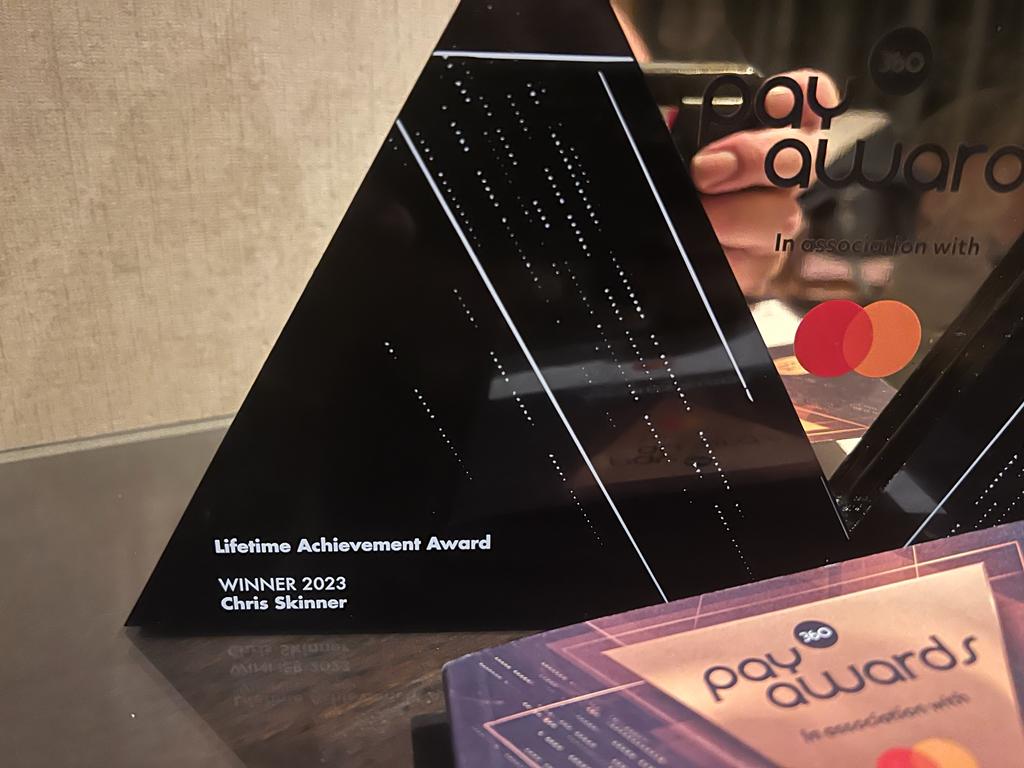

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...