It’s over five years since the Global Financial Crisis (GFI) began, and the regulators woke up to the fact that a small number of banks had become Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFIs).

Ever since, the powers that be have been working to prune, reshape and restore confidence in the system and yet, as the years go by, maybe the system is sorting itself out naturally.

You only have to look at the SIFIs to see how they are reshaping themselves.

Bank of America has sold off many of its assets, particularly the cards business they acquired from MBNA; JPMorgan suffered a whale of a time in London and is rethinking its global operations; HSBC has pulled significantly out of key markets, specifically the USA; RBS has sold nearly all of its crown jewels to recapitalise, with Citizens Bank on the agenda later this year; Barclays has retrenched and has tried to get rid of the Bob Diamond culture of greed that tarnished Barclays Capital; and so on.

Most bank CEOs have changed, along with most of the leadership team that goes with such change, and there is an attempt to reshape the cultural mind-set of banking to being one that is more honest, more ethical and more risk averse.

The only exception to this change appears to be Goldman Sachs.

Why?

Because Goldman Sachs is still running in overdrive, hasn’t changed CEO and is as aggressive in seeking alpha as they have ever been.

In fact, Goldman Sachs is actually the most interesting bank in terms of aggressive competitiveness.

Founded in 1869, the banks foundations were in the alternative finance markets. In the 1950s, the bank was a key player in founding the municipal bond markets and, in the 1970s, Goldmans then co-head John Whitehead, wrote the ten key principles to guide the banks staff in the future.

These ten principles were:

- Don’t waste time going after business you don’t really want.

- The boss decides, not the assistant treasures. Do you know the boss?

- It is just as easy to get a first-rate piece of business as a second-rate one.

- You never learn anything when you’re talking.

- The client’s objective is more important than yours.

- The respect of one person is worth more than an acquaintance with 100 people.

- When there’s business to be found, go out and get it.

- Important people like to deal with other important people. Are you one?

- There’s nothing worse than an unhappy client.

- If you get the business, it’s up to you to see that it’s well handled.

These guiding principles seem very different to the firm that Greg Smith resigned from in 2012, publishing his resignation letter in the New York Times.

A key part of that letter describes the culture today.

What are three quick ways to become a leader?

- Execute on the firm’s ‘axes’, which is Goldman-speak for persuading your clients to invest in the stocks or other products that we are trying to get rid of because they are not seen as having a lot of potential profit.

- ‘Hunt Elephants.’ In English: get your clients – some of whom are sophisticated, and some of whom aren’t – to trade whatever will bring the biggest profit to Goldman.

- Find yourself sitting in a seat where your job is to trade any illiquid, opaque product with a three-letter acronym.

How did the guiding principles of the 1970s become translated into this stich up the client attitude of the 2000s, nad did the ethical partnership of the 1970s really become the Vampire Squid of the 2000s?

Some say that the fault lies with the conversion of Wall Street partnerships to proprietary firms in the late 1990s, just as Glass-Steagall fell apart and Gramm-Leach Bliley came into force.

The decision to reverse the separation of investment and commercial banking that these acts enabled, under duress from the then most forceful bank leader in America (Sandy Weill, CEO of Citigroup) was a key part of this change, as was the move from the trade in real stocks and shares to futures, derviatives and exotic instruments.

During the 1980s, just as we saw with Gordon Gekko in Wall Street, Michael Milken the junk bond king and his firm KKR became Barbarians at the Gate and infectious greed, as Alan Greenspan referred to the phenomena, became the mantra of the Wall Street firms.

The Wolf of Wall Street with his focus upon selling penny stocks, along with American Psycho, Liars Poker and more, sum up the change in culture in the investment bank world, and the previously gentlemanly era of trading moved into a raucous and now automated world of beat the rest at whatever cost.

Dog eat dog and win at all costs became the focal culture for the masters of the universe, and Goldman Sachs was no exception. After all, this greed was infectious.

It was well illustrated by people such as Frank Quattrone at Credit Suisse who, along with many others, started to blur the line between honest and ethical and questionable and legal.

A little like Chris Moyles and Jimmy Carr avoiding tax at any cost, bankers became animals that wanted to make money at any cost.

Lines were blurred between client advisory research and selling junk stocks, and everyone basked in the glory of the riches that could be made, regardless of the cost.

I always quote a line from Liars Poker during this era, where Salomon Smith Barney’s General Counsel states that his “role is to find the chink in the regulator’s armour”.

Creating risk creates rewards creates profits creates bonuses.

John Whitehead’s principles combined with infectious greed guided Goldman Sachs to become the most important market making firm by the 1990s and, as Wall Street partnerships saw megabucks through conversion into publicly listed entities, so too did Goldman Sachs.

The real big difference after the IPO was that many of the partners and staffers became multimillionaires overnight, as the value of their stock ballooned.

For example, at IPO, Lloyd Blankfein’s 0.9% stake in the company became worth $148.5 million as did Richard Friedman’s, Robert Steel’s and many others.

The partenrs were made for life.

Equally, the other big change was that the partners were now betting other people’s money rather than their own, hence the idea of getting the rubbish off their books and onto their customers’ books became a focal point.

That’s at least a contention in former Goldman employee Steven Mandis, who produced a book about the firm in September 2013: What happened to Goldman Sachs?

But are the words of Greg Smith and Steven Mandis potentially those of weaker people who were eventually over-looked in the management hierarchy of Goldman Sachs and hence get passed over for status and rewards?

That may be a case in point, as Fortune Magazine voted Goldman Sachs the 45th best place to work in America in 2014, well ahead of other mainstream banks and financial institutions, and Goldman has earned a spot on the list every year since it started in 1998. It's one of just thirteen companies that can make that claim.

It's not just the pay that makes the employees so fond of their firm. Nor is it the swank corporate headquarters, the four-month maternity leave, or an obsessive devotion to philanthropy. Above all else, employees say, it's the opportunity to work with, and count yourself among, an ultra-elite group. Less than 3% of 97,600 applicants for analyst and associate roles won a seat at the firm last year, making it twice as hard to get into as Harvard. That, plus what employees describe as a flat, consensus-driven, collaborative culture, is what they say they like about their company.

“You don't have to be the smartest person, but it's probably the highest combination of smart and interesting and interested-in-the-world kind of people”, says Lloyd Blankfein, the 31-year veteran who became chairman and CEO in 2006.

So whatever you think about Goldman Sachs, it is one of the last banks that have survived this and many other historical crisis.

That’s down to being nimble and adaptive, strong and aggressive, and having a culture of “extreme aggression, deep paranoia, long term orientation, individual ambition and robot like teamwork”.

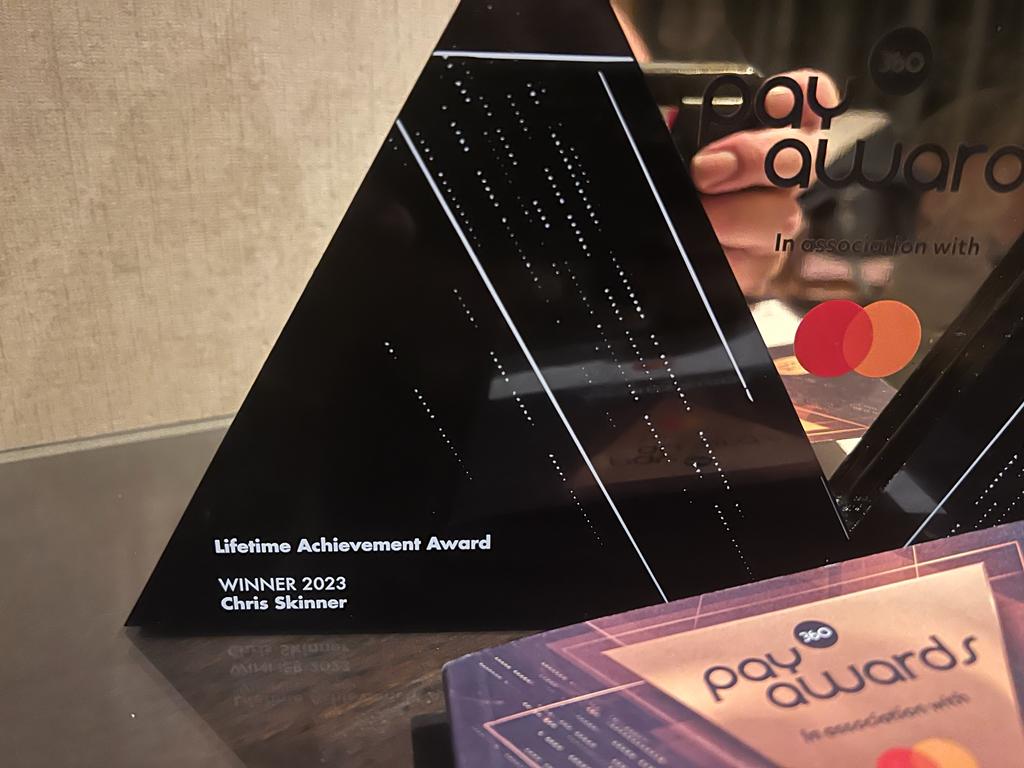

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...