This is the final part of a series about how the City of London developed its financial prowess and system. Previous entries include:

- Part One: The Romans

- Part Two: The Vikings

- Part Three: Medieval Times

- Part Four: The Tudors

- Part Five: The Stuarts

- Part Six: The Bank of England

- Part Seven: Lloyd's of London

- Part Eight: The London Stock Exchange

- Part Nine: The 1700s

- Part Ten: The Victorians

- Part Eleven: World Wars

- Part Twelve: After World War II

- Part Thirteen: The Big Bang

- Part Fourteen: Crisis

Once the City had been deregulated in 1986, things really started to move.

Trading became more focused, frenetic and competitive, and markets moved millions and then trillions in minutes, instead of the old ways which were days or months.

London was now rocking, with many overseas banks basing themselves here, the Eurocurrency markets thriving and electronic trading growing fast into program trading, algorithmic trading and now high frequency trading.

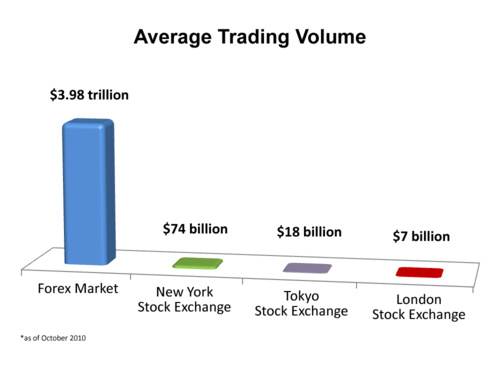

FX trading globally grew from half a trillion dollars a day to five trillion a day over the 1988-2011 period …

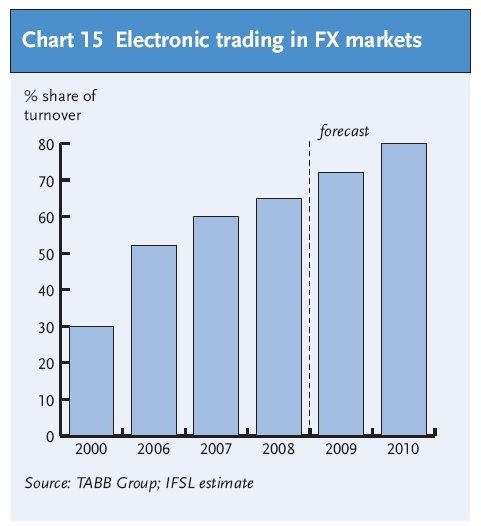

Most of such trading is electronic:

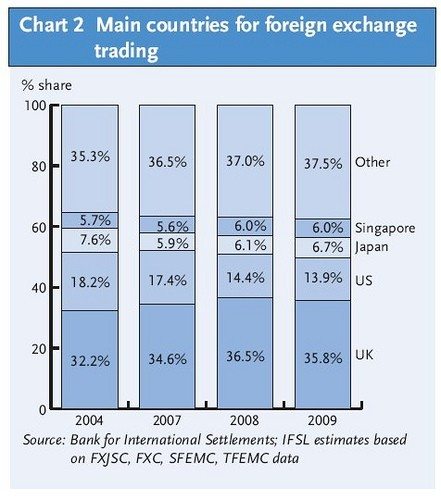

With London dealing with a third of such trading.

The London Stock Exchange is now processing over €100 billion of trades a month (around €5 billion a day), although that still leaves the markets dwarfed by Tokyo and New York:

During this time, the London markets had become attractive to overseas firms due to the open access to skills and capabilities that, by comparison to anywhere else in Europe, is second to none.

This is illustrated by London’s importance as a European financial centre, with the UK managing 36% of the EU's wholesale finance industry and a 61% share of the EU's net exports of international transactions in financial services (from the December report of Open Forum Europe).

But none of this would have happened if the deregulation of the markets that took place in 1986 hadn’t internationalised the London markets, and made them more open to overseas entry and automation.

This was based upon an easy way of doing business using principles-based light-touch regulation.

The phrase principles-based light-touch regulation is one ew use regularly now.

Under Thatcherism it was actually a move towards self regulation, with each industry segment - insurance, retail banking, investment banking, building societies and more - having their own industry body to manage their activities.

It created a free and open industry, attractive to all for its ease of doing business, and regulated by industry elected officials.

This light touch regulatory environment was reinforced by New Labour, who succeeded Thatcher’s Tories in the mid-1990s.

The new government rapidly introduced change, the most major of which was to take monetary policy from the Treasury and give these powers to the Bank of England.

This was followed by the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, to improve regulations after the collapse of Barings Bank and Equitable Life, where the light-touch self-regulatory approach was seen to fail.

The new Act therefore moved all financial markets regulation into one body: the Financial Services Authority (FSA) in 2000.

This all powerful body had been created as a principles-based light-touch regulator, in keeping with the self-regulatory approach under the previous system, but with more powers to enforce the rules.

The markets were now faced with a co-ordinated agency with two key roles: to create effective regulation and to police and ensure that firm’s comply with the regulations through their general conduct of business.

It was a move that was applauded by many, and emulated by many, and further enhanced the City’s reputation as an open platform for finance, where it was easy to do business with effective governance.

However, it also created a tense relationship between the FSA, the Bank and the Treasury, as none of them had the complete ownership of their turf.

The FSA regulated the firms; the Bank looked after monetary policy; and the Treasury managed fiscal policy.

The division often overlapped and therefore created friction, as demonstrated by activities in 2002 when the Treasury Select Committee accused the FSA of being ‘asleep on the job’ over the split-capital debacle. The same committee accused the Bank of England of being ‘asleep on the job’ over Northern Rock five years later.

Neither were asleep on the job if we’re truthful. The truth is that they are just understaffed, underfunded and under capable.

The markets move faster than regulators, and the real challenge is to come up with regulatory structures that are effective enough.

The FSA was not far away from that, but it cracked under the pressure of two forces – lack of competent people; and a global financial crisis that no country anticipated.

In the first instance, the FSA lacked truly competent people to manage City firms. In fact, they lacked competent people all around.

The FSA admit, for example, that they did not manage Northern Rock well.

Why?

Because Northern Rock was over 200 miles north of London and so the bank would receive no visits for months or, sometimes, years. There was one period where Northern Rock had no visit from the FSA for over 18 months.

From the FSA’s review:

“The Internal Audit review identifies the following four key failings specifically in the case of Northern Rock:

- A lack of sufficient supervisory engagement with the firm, in particular the failure of the supervisory team to follow up rigorously with the management of the firm on the business model vulnerability arising from changing market conditions.

- A lack of adequate oversight and review by FSA line management of the quality, intensity and rigour of the firm's supervision.

- Inadequate specific resource directly supervising the firm.

- A lack of intensity by the FSA in ensuring that all available risk information was properly utilised to inform its supervisory actions.”

But it goes deeper than this, in that most banks try to find gaps in regulations to make money.

It’s called regulatory arbitrage, and banks are very good at this.

As Michael Lewis quotes Salomon Smith Barney’s General Counsel in Liar’s Poker: “my role is to find the chinks in the regulator’s armour”.

So regulators can only keep up if they have the best people but, in the case of investment markets, the best people cost too much.

With a high cost for a decent investment banker, hiring a lot of them to be auditors, regulators and police is just too tough.

This was illustrated well by the second challenge: the Global Financial Crisis.

The crisis has been covered well over the last few years – if you’re keen to know more then you should buy my book about it (recently reprinted and updated) – and the core of the coverage says that regulators, governments, bankers and all messed up.

This is discussed in depth in a recent interview with the current Chair of the FSA, Adair Turner:

The FSA made mistakes “but you do have to place them within that wider context—the whole system… was deeply, deeply wrong … the global regulatory system in total failed.”

The framework for setting capital levels, designed by committees of senior bankers across the world, “was an enormous amount of intellectual effort over ten years which completely failed to address the fundamental issues …

“We constructed an economic theory that this was all fine because financial markets had got so much more sophisticated—that liquidity problems wouldn’t emerge because markets across the world had become more liquid and sophisticated, [that] the banks could run with lower capital because the techniques of risk management had become more sophisticated. And all this was just hugely wrong …

“There was a belief that light-touch regulation, or limited-touch, would make the City bigger, and that the City was a source of employment and tax revenue. And therefore there was clear pressure on the FSA at times to say, ‘Go easy on the City.’ The FSA never used the phrase ‘light-touch,’ but politicians did, and they did it in speeches which were directed at the FSA.”

Which politicians?

“Oh—ministers right at the top. Prime ministers. Chancellors of the exchequer, made speeches of that sort, in the last government.”

There was also pressure for the regulator to be an advocate for the City, he said. Regulators “mustn’t do crazy things that will necessarily harm [the sector]. But the moment you introduce an idea that they are part regulator and part, as it were, sponsor, spokesman, for an industry, that’s dangerous, that’s confusing.”

The result was that London became a centre for some of the most damaging financial activity. One example was AIG Financial Products, which specialised in issuing credit default swaps (CDS), a form of insurance against borrowers failing to meet their debts. In the run-up to the crash, the Mayfair-based AIG FP issued over $2 trillion worth of derivatives, activity that enhanced the spread of the global crisis.

“Well, AIG Financial Products in Curzon Street was actually regulated by the French,” said Turner. “It was the French regulator. There is a major issue here about clarity of who is responsible. If you set up in London, as a branch of a European legal entity, then the single market rules are very clear that the local regulator has only limited control over what you do …

“One sometimes feels that this financial system is like some incredibly complicated waterbed, where you try and deal with something here and then something happens at the other end. We’re just not clever enough to see it.”

In hindsight, it’s easy to beat up on all the things that went wrong – governance, government, regulator, shareholder, markets, the world – but the bottom-line is that the credit crisis has seriously damaged London’s reputation for getting things right when, in retrospect, it got things so wrong (more in the FSA’s more recent moratorium into the collapse of the Royal Bank of Scotland).

Going forward, the answer is not necessarily the action being taken by the UK and European governments today however.

On the one hand, you have a transaction tax that Europe wants to impose, which is sound in principle but not in practice.

Sweden has already shown that such taxes don’t work, and the only place that will be seriously hit by such a tax is London – remember that 61% of all international financial transactions in Europe take place in London today – which is why David Cameron exercised his veto on the European treaty at the end of 2011.

Then you have the UK’s plans to separate commercial and investment banks. It’s like a Glass-Steagall, but allows the UK to have ring-fences rather than complete separation.

Again, everyone is split on this recommendation with Paul Volcker, the former head of the Federal Reserve and the man charged with reform of the US investment markets through ‘the Volcker Rule’, saying that he doesn’t “believe in a firewall or Chinese wall, as you need a very high ring fence to stop the deer jumping over.”

True.

Regardless, the Vickers recommendations to ring fence banks are estimated to cost UK banks at least £10 billion a year in lost revenue, so that’s not good for London either.

Finally, you have the one thing that may be appropriate: the end of the FSA.

In June 2010, the UK government announced the end of the FSA. This will repeal the changes introduced by Tony Blair’s government, where the financial markets were run by a triumvirate of the FSA, the Bank of England and the Treasury.

The aim is to place more power into the hands of the Bank of England, with the regulatory part of the FSA becoming part of their operations.

From 2013, the FSA will therefore be split into two new regulatory bodies:

- The Prudential Regulation Authority (the PRA), which will be a subsidiary of the Bank of England, will be responsible for promoting the stable and prudent operation of the financial system through regulation of all deposit-taking institutions, insurers and investment banks.

- The Financial Conduct Authority (the FCA) will be responsible for regulation of conduct in retail, as well as wholesale, financial markets and the infrastructure that supports those markets. The FCA will also have responsibility for the prudential regulation of firms that do not fall under the PRA’s scope.

Will these changes succeed?

Will the City still be as strong as ever?

Will it maintain its #1 position as the financial hub of Europe and the World?

Who knows.

All we can say is that London has always been at the heart of the world’s trading activities from Roman and Viking times to the present day.

Through Empire and Industry, London has cemented its position as the leading centre for finance.

And by political and economic manoeuvring, has maintained that position throughout the last century, as the Empire disappeared and open borders created free trade.

It will be interesting to see where London’s position move over the next decade as reforms kick in to restructure London, to make it a safer place to trade once more.

This is the final part of a series about how the City of London developed its financial prowess and system. Previous entries include:

- Part One: The Romans

- Part Two: The Vikings

- Part Three: Medieval Times

- Part Four: The Tudors

- Part Five: The Stuarts

- Part Six: The Bank of England

- Part Seven: Lloyd's of London

- Part Eight: The London Stock Exchange

- Part Nine: The 1700s

- Part Ten: The Victorians

- Part Eleven: World Wars

- Part Twelve: After World War II

- Part Thirteen: The Big Bang

- Part Fourteen: Crisis

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...