By the 1970s, the City had re-established its position of prominence thanks to trading in Eurocurrency and the increasing volume of trading in securities, but it lagged behind the rest of the world, particularly New York, due to its very traditional way of operating.

The markets were based upon a structure that was 150 years old, where gentlemen stockbrokers dealt with client needs and gave orders to jobbers who would make the trades.

The system started when many members of the Stock Exchange began to specialise in one of the leading types of securities during the nineteenth century.

These players were defined as ‘market-makers’ or jobbers, and the brokers who dealt with them on behalf of the public had a clear-cut separation.

This separation was made a formal one, when it was embodied in the Stock Exchange rules in 1909. The rules had been created to ensure that those taking orders were not creating dishonest trades, by inflating prices or concentrating investments through conflicting market making interests.

By 1914 there were over 600 jobbing firms as well as many one-man jobbing operations.

These numbers then steadily declined as the institutional investor supplanted the private one, which meant that the scale of capital required to be a jobber – as you had to cover your trading positions with collateral – increased dramatically.

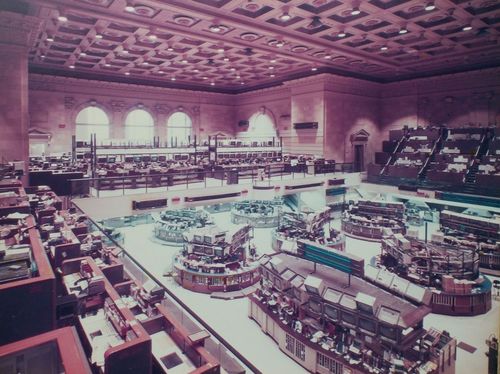

Picture of the Stock Exchange Trading Floor, 1968, from the Museum of London

On the eve of 'Big Bang' there were five major jobbing firms on the floor of the Stock Exchange: Akroyd & Smithers, Wedd Durlacher, Pinchin Denny, Smith Brothers, Bisgood Bishop and Charles Pulley.

Meanwhile, the large stockbroking firms were Seligman Harris, Phillips & Drew, Capel Cure Myers and Quilter & Co. Their business was based upon schmoozing clients over long lunches, and the City was renowned for imbibing, massive entertainment bills and general high life activities.

Philip Augar tells the story well in his book The Death of Gentlemanly Capitalism, where a broker hears that his secretary lives on an estate in Romford, and replies: “How splendid. Do you keep horses there?”

No wonder the gentleman brokers were stereotyped as public school educated oafs from Harrow or Eton, whilst the jobbers were viewed as all being cheeky cockney boys who were loud and brash.

A very old world [to see the world of the old stock exchange, click here which links to a 47 minute BBC documentary from 1964 on the Stockbroker’s World].

Both the jobber and broker made money.

The jobbers made money by making markets, as every stock transaction had to be recorded in their books; the brokers made money through commissions from their clients, which were fixed; and both functions were firmly separated.

The real focus of the separation was made with the best of intentions: to avoid conflicts of interest, where a broker might falsely make trades in stocks where they had an interest themselves. This is important as some feel that today's issues are caused by the fact that such separation was removed

This is similar to the view that the repeal of Glass-Steagall by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 in the USA, which removed the separation of investment banking from retail banking, was a mistake.

The separation of market maker and stockbroker caused issues for the City of London’s competitiveness, particularly by the 1980s when the volume of trading through London’s markets was just 1/13th of that being traded in Wall Street.

This was down to the innovations coming from across the Atlantic.

The New York Stock Exchange in the 1980s, courtesy of Flikr

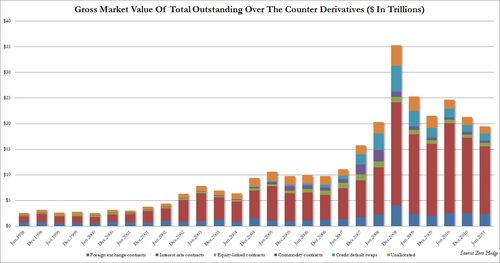

In particular, the rise of technology had given way to new ideas about finance, and derivatives began to emerge as a way of creating futures markets.

The theories were based upon two professors, Fischer Black and Myron Scholes, who modelled risk equations and, in 1973, publish a paper: “The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities”, which articulated a theory that any asset could be perfectly offset in risk terms by another investment.

A hedge, so to speak.

The markets embraced the concept immediately and this became known as the Black–Scholes equation, the mathematical theory that governs the price of an option over time.

The way the theory works it that you can create a derivation of an asset, and perfectly hedge the risks of that asset in a way that will “eliminate risk".

So I can take part of an investment in the stocks of General Electric, and hedge this with an option in oil commodities for example, in the belief that GE stock price will fall when oil prices rise and vice versa; or I can take an FX trade in Dollars and hedge this with an option in Yen for the same reason.

The pairing of risks on the basis of options for the future, using the Black-Scholes formula, combined with trading in parts of related assets and instruments - derivations - forms the basis for much of all market trading today.

It led to the rise of derivatives and OTC derivatives; the creation of new exchanges like the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange (LIFFE) and Eurex; and is a huge part of the volume of trading that goes through today’s high frequency trading automated systems.

The Rise of OTC Derivatives Contracts, from Zero Hedge

Wall Street adopted the derivatives markets rapidly, and also introduced automation for programming trades to allow more complicated mathematical models to operate as part of this new, more complex world.

These developments pushed London into a backwater.

It used to be “absolute hell with a wooden floor. You’d come back to the office at 3pm and blow your nose, and clumps of brown wood dust would come out.” Fred Carr, Partner at Capel-Cure Myers in the 1980s

By 1986, London trading volumes were a thirteenth of New York’s and a fifth of the size of Tokyo; Frankfurt and Paris were rising as serous European alternatives; and London appeared fusty and old.

It was time for change.

Margaret Thatcher’s Government and her Minister for Trade and Industry, Cecil Parkinson (a former guest speaker at the Financial Services Club) introduced the Financial Services Act of 1986.

This had a dramatic and profound effect upon City life.

The aim of the Act had many implications but, for the City, it was driven by four key principles:

- Internationalisation, allowing overseas firms to compete in the London markets;

- Deregulation of the fixed commission rule, so that stockbrokers had to become far more competitive;

- Proprietary transactions allowed, eradicating the separation of the broker and market maker and encouraging trading off your own book of business; and

- The opening of ownership of Stock Exchange members to outsiders, encouraging a wave of acquisitions and mergers.

In particular, the Act created competition between brokers - before Big Bang, commissions were fixed and so brokers did not compete on commission rates - and not only allowed brokers and jobbers to merge, but also abolished any oversight of the law courts on derivative contracts that might be considered speculative or contrary to the Gaming Act of 1845, e.g. ‘betting’.

A flurry of mergers and acquisitions followed, with the best deals going to those who jumped first.

For example, Security Pacific bought 30% of Hoare Govett, the top equity broker, in September 1983 at an implied value of £27 million. When they purchased a further 60% ten months later, the firm was worth £80 million.

By 1986, strategies had been chosen and implemented. Stockbrokers left their old premises, typically six-storey 1960s monstrosities, and moved into glass skyscrapers.

The actual day of change was 27th October 1986.

It was called the Big Bang because so much changes had to be implemented on one day: the elimination of fixed commissions; a marked increase in the number of market participants; a change in the structure and ownership of trading firms; and perhaps most importantly rapid movement of stock trading off the floor of the Exchange.

This remains the most rapid and complete regulatory reform of any market, and the most striking example to date of a regulatory event engineered to benefit the local financial industry.

A key impact was the introduction of a wave of new technologies.

The London Stock Exchange rapidly moved from open outcry – where the jobbers would shout “buy, buy, buy” and “sell, sell, sell” across the trading room – to a completely automated system, with program trading.

This led to algorithmic trading and now high frequency trading.

Today's "trading floor", from FinTechIsrael

The end of open outcry meant that trade times shortened from ten minutes to ten seconds back in 1986 (today, it’s nanoseconds).

Combined with the market opening two and half hours earlier and closing two hours later, this meant that trading volumes rocketed up 72% in 1986 and 56% in 1987.

London was rocking.

The Big Bang allowed London to follow Wall Street into automated trading of more and more complex instruments – the exotics as many derivatives products are termed – and, since the early 2000s, the City has been back on top of the Global Financial Centres Indices.

This is all down to the Big Bang of 1986.

The Big Bang made London a completely free and open trading location for all, with overseas firms welcome and all of the skills required to create liquidity based here – accountants, lawyers, technologists, auditors, advisors, consultants and more.

Over a million people work in the City today, and much of the Big Bang’s changes hailed the systems and structures that operate today, including those that allowed the credit crisis to occur.

This is because many of the theories around derivatives were wrong, and have proven to be wrong again and again.

Add technologies to turbo-charge these incorrect beliefs and markets fail faster and larger than ever before.

But the markets adopted these capabilities and practices as it creates liquidity.

Liquidity creates alpha, and alpha creates profits.

As can be seen, the effects of Big Bang were dramatic with London's place as a financial capital decisively strengthened to the point where it is arguably the world's most important financial centre.

An economic boom created a new class of nouveau riche – the Yuppie (young, upwardly mobile, professional) – that has persisted since the 1990s, and the boom expanded beyond the City into new developments in East London with the rise of Canary Wharf.

More on this tomorrow, but here are a few key events and dates that led up to the crisis:

1979 Margaret Thatcher and the new Conservative Government strive towards a ‘free market’

1982 Formation of LIFFE the London derivatives market

1986 ‘Big Bang’- the deregulation of the financial industry, and the movement from the Stock Exchange floor to screen and telephone based dealing mechanisms

1980’s Boom in privatisation issues (British Telecom, British Gas, British Airways,) as the British public share in the profits of the companies / services they use

1987 Black Monday - stock markets crash, compounded by traders taking speculative positions on the weakening sterling

1995 Barings bank ‘bankrupted’ by a rogue trader

1995 London Stock Exchange opens AIM the Alternative Investment Market (targeted at smaller developing companies)

1999 Stockmarkets reach record ‘highs’ – the effect of the momentum behind the dot.com boom

2003 The bottom of the ‘trough’ following the dot com bubble bursting and a deceleration in merger and acquisition activity

2004-2007 Company profits grow, takeover and merger activity increases, sophisticated financial products and gearing magnify gains and the market peaks at 6751

2008 Market falls on the back of a Global Banking Crisis as liquidity between major Global Investment Banks dries up

2009 The FTSE 100 reaches a low of 3460

2011 A New Act: the Government recommends new laws to separate Commercial and Investment Banking as a result of the Global Banking Crisis

The City of London by the Numbers (from the FT)

1986 2005

Domestic equities annual turnover LSE (£bn) 161 2,495

Foreign equities on LSE 0 2,703

UK government securities 424 3,231

Foreign exchange daily turnover ($bn) 50 1,210

Long-term annual premiums (£bn) 21 110

London exchange derivatives contracts traded (m) 17 (1987) 999

UK banking sector assets (£bn) 762 (1985) 5,526

Number of UK private equity funds 19 54

UK private equity amount raised ($m) 360 46,170

UK private equity (as a % of Europe) 3.9% 66.7%

Asset under management (£bn) 3 (1990) 89

Number of active firms 17 66

Capital raised by vinage year (£bn) 0 29

Much of this blog entry is based upon a number of essays about the Big Bang, so here’s a little more reading if this interests you:

- London's Big Bang: a case study of information technology, competitive impact, and organizational change, by Eric K. Clemons and Bruce W. Weber

- Big Bang's 25th Anniversary and the Credit Crunch, by Spear’s

- London's Big Bang at 25, origin of today's financial universe, by Reuters

- London insiders remember Big Bang, by the BBC

- Happy Anniversary? Big Bang's 25 Silver Years, by Sky News

- The Big Bang, by the Financial Times

This is the thirteenth in a series about how the City of London developed its financial prowess and system.

Previous entries include:

- Part One: The Romans

- Part Two: The Vikings

- Part Three: Medieval Times

- Part Four: The Tudors

- Part Five: The Stuarts

- Part Six: The Bank of England

- Part Seven: Lloyd's of London

- Part Eight: The London Stock Exchange

- Part Nine: The 1700s

- Part Ten: The Victorians

- Part Eleven: World Wars

- Part Twelve: After World War II

- Part Thirteen: The Big Bang

- Part Fourteen: Crisis

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...