Britain came out of the Second World War a weaker nation. The economy was in ruins, as was much of Europe’s economies, and it owed $3.5 billion to the USA as a result of a loan in 1946 which was only repaid in 2006, sixty years later.

The declaration of independence of India in 1947 began the true decline of the Empire, and the nation moved from being a dominant force to being second tier behind the newly empowered North Americas.

Britain’s financial system and influence was also in tatters, as a result of the wars.

First, the City had undergone a major crisis of confidence when the pound sterling was suspended from the Gold Standard in 1931 due to its over-valuation (as mentioned yesterday).

Then it defaulted on loans when, in 1934, Britain owed America £866 million (about £40 billion today), whilst other nations owed Britain £2.3 billion back then (about £104 billion today).

These loans were never repaid and country imbalances caused major issues before the Second World War.

In order to avoid such issues happening again, a meeting was called for all of the Allied nations to create a new system, with rules and procedures for managing the commercial and financial relations between nations.

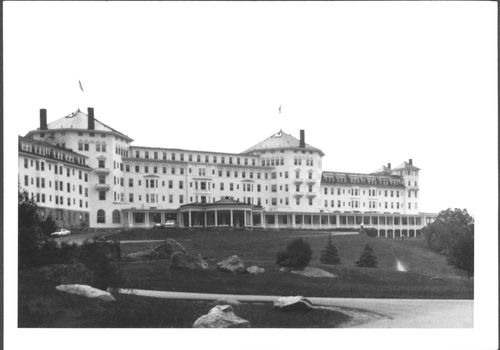

The meeting was held at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States, in July 1944 and resulted in the Bretton Woods Agreement.

Picture from the IMF Archives

The Bretton Woods Agreement established the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), today part of the World Bank, both of which became operational in 1945.

It was a historic agreement as, for the first time in history, the World had a monetary policy. Fortunately for all, it created the IMF and foundations of the World Bank; unfortunately, it also had a major flaw: the Gold Standard.

Bretton Woods based all of its underlying assumptions upon nations working with a global gold standard. Each country signing the agreement promised to maintain its currency at values within a narrow margin to the value of gold, with the IMF established to facilitate payment imbalances on a temporary basis.

This system worked for 25 years, during which time America became the dominant financial superpower, superseding the City in importance.

America generated half of the world’s industrial output, had huge gold reserves – America had a gold stock that amounted to $20 billion, roughly 60% of the total official gold reserves of the world – and a buoyant and stable environment for growth.

With such an invigorated country, the dollar became king and new industrial monsters rose from the ashes of the War, and were all American in flavour – IBM, General Electric, Standard Oil and more.

These were all based in the USA and gave rise to powerful American commercial banks. For example, in 1954, the New York based commercial banks held $35.4 billion in assets, compared to $19.4 billion in London.

New York also beat the City in terms of loan issuance, brokering $4.17 billion in foreign loans between 1955 and 1960, compared to $1.06 billion in London.

Although the dollar was king, it was also pegged to the Gold Standard under Bretton Woods, and this was a fatal flaw in the agreement.

As mentioned, America had a gold stock that amounted to 60% of the world’s total gold reserves. In 1957, the United States gold reserves exceeded the total dollar reserves of all the foreign central banks by a ratio of three to one.

However, by pegging international currency to gold, it failed to take into effect the change in gold's value and set the amount at $35 an ounce. This was the value of gold in 1934, when the gold standard levels had been set.

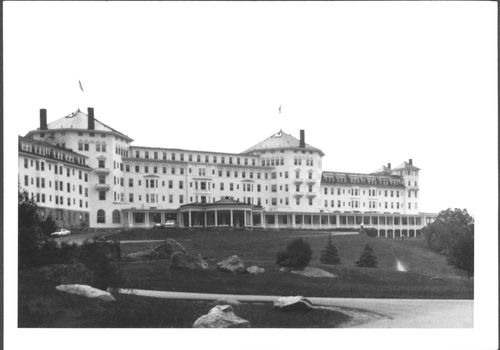

During and after World War II, the dollar lost substantial purchasing power and, as European economies built back up, the ever-growing drain on US gold reserves saw the Bretton Woods Agreement fail as a permanent, working system when America left the Gold Standard in 1971.

Picture from Gloves Off

The departure of the dollar from the Gold Standard still left the dollar as the reserve currency of the world, but increased trading in an already buoyant Eurodollar market, where London was the major financial centre for such dealings.

Eurodollars are bank deposits made in US dollars at banks outside the United States, and therefore not under the jurisdiction of the Federal Reserve.

After the Second World War, the quantity of US dollars outside America had increased enormously, especially as the dollar was the dominating currency.

The dollars increase in importance was due to several reasons but particularly due to Bretton Woods and the Marshall Plan – the US loans to Europe to speed European recovery – along with massive imports into the US, which had become the largest consumer market due to the dollar’s buying power.

These developments meant that enormous sums of US dollars were in the custody of foreign banks outside the United States.

London became the focal point for trading in these dollars, with the Eurodollar developing as a result of concerns about bank holdings being seized by the Federal Reserve if they were kept in America.

This is why the Eurodollar first appeared in 1956.

At the time, the Cold War was raging between the Russia and America, and the Soviet Union feared that its deposits in North American banks would be frozen.

Picture from Designer Daily

They therefore moved their holdings to the Moscow Narodny Bank, a Soviet-owned bank with a British charter. The British bank then deposited the money in the US banks in the certainty that there would be no chance of confiscation as the money belonged to a British bank.

The City of London banks built their stature into a major Eurocurrency – any bank deposits of a currency outside the country that issued the currency – centre. According to the Bank of International Settlements, the Eurocurrency markets grew from $9 billion in 1964 to $57 billion by 1970, and then to $661 billion in 1981.

How London became so pivotal during this period is partly down to the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement, but also due to the oil-price shocks of the 1970s, both of which fuelled trading in the Eurocurrency markets.

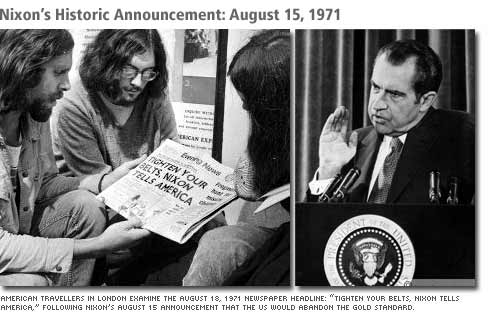

During the 1960s, oil production in the USA peaked and the Middle East nations became integral to oil supply. These nations were not necessarily predisposed to American and European markets – as can be seen today with the conflicts across the region – and hence there were escalating crises in supply, with the worst occurring in 1973 and 1979.

The 1973 crisis occurred when the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) i proclaimed an oil embargo and 1979 was caused by the Iranian Revolution.

Picture from Heating Oil

During this time of conflict – the Cold War and Energy Crisis – London was seen to be a place of political neutrality and this made it a choice for Arab countries, Russians and others to place business.

This is why London has so many overseas, international and foreign banks and securities firms operating in the City and is the foundation of today’s City of London as we know it.

However, the City was still hamstrung by issues of tradition and practice, as illustrated by the culture of the jobber and broker, or blokes and chaps.

Jobbers were runners basically, and were dodgy divers from the East End of London; brokers were gentlemen however, and were schooled through Eton and Harrow with Top Hats and tails.

The barrow boy and gentleman came together in the City’s trading rooms, where a clash of cultures pervaded.

This clash was finally put to bed in the 1980s when Margaret Thatcher’s government reformed the City through the Big Bang.

That’s tomorrow’s story.

Meanwhile, we cannot lose sight of the Bretton Woods Agreement and the Gold Standard, as it is always revived in times of economic crisis.

For example, after the Asian Crisis of 1997 , the world’s markets discussed the possibly of a Bretton Woods II and even now, we have the same discussions. From a Bank of England report published on December 12th 2011:

“The evidence is that today’s system has performed poorly against each of its three objectives, at least compared with the Bretton Woods System, with the key failure being the system’s inability to maintain financial stability and minimise the incidence of disruptive sudden changes in global capital flows.”

Large extracts of this blog entry are taken from various sources, including Wikipedia (obviously) and books such as “Readings in Urban Theory” by Susan Fainstein and Scott Campbell, and “The Evolution of Great World Cities” by Christopher Kennedy.

This is the twelfth in a series about how the City of London developed its financial prowess and system.

Previous entries include:

- Part One: The Romans

- Part Two: The Vikings

- Part Three: Medieval Times

- Part Four: The Tudors

- Part Five: The Stuarts

- Part Six: The Bank of England

- Part Seven: Lloyd's of London

- Part Eight: The London Stock Exchange

- Part Nine: The 1700s

- Part Ten: The Victorians

- Part Eleven: World Wars

- Part Twelve: After World War II

- Part Thirteen: The Big Bang

- Part Fourteen: Crisis

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...