It’s September 14.

It’s exactly ten years since Lehman Brothers collapsed.

It’s ten years since the touchpaper was lit that sparked the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

It’s exactly ten years since I landed in Vienna for Sibos 2008 on Sunday, September 14 2008, to find voicemail after voicemail asking for commentary about the crisis. Lloyds took over HBOS; RBS had to be taken over by the government; Washington Mutual was forced into the hands of JPMorgan Chase; Merrill Lynch disappeared into Bank of America; Commerzbank had to be given resuscitation; and so on and so forth.

The ground shifted.

Billions of dollars of central bank issued quantitative easing saved the US and UK economies, whilst the ECB didn’t do this resulting in a sovereign debt crisis just a few years later across Europe. Greece needed a bailout and Spain, Portugal, Italy and Ireland sailed close to the wind, and still do in the case of Italy.

Here's a statistical breakdown from The Week of the fallout from the crisis and its repercussions over the past ten years that shows how the crash has reshaped the UK economy.

$150 billion

The total – around £115 billion in today's money – that global banking groups have paid out in the US in fines relating to the financial crisis, according to the FT.

Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) is still awaiting news of its fine for mortgage bond mis-selling from the US Department of Justice and Barclays is challenging its own lawsuit, so that figure is only likely to rise.

The Independent says that banks globally have paid $321 billion (£262 billion) in fines since 2008 in relation not just to the financial crisis but also to past misconduct. This includes market manipulation and money laundering failings.

£137 billion

The eventual cost of bailing out the UK banking industry in 2008 and 2009, says the FT.

With RBS still mostly in government hands and worth less than half what it was back then, the UK government's forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility, reckons that total losses on that investment could reach £27 billion.

4.3%

So-called "tier 1" core capital reserves – the cash held back to shore up the balance sheet in the event of a downturn that causes loan defaults – that UK banks held on average in 2006, says What Investment.

14.8%

Tier 1 capital held across the UK banking sector now, according to Bank of England figures. The change has been driven by regulation and implies a far higher cost of capital for banks to lend.

$30 billion

The total profit – worth £23 billion – made by US banking groups in the second quarter, says Bloomberg. The figure is "just a few hundred million short of the record in the second quarter of 2007".

Inflation means that in "real" terms the profit is worth much less now. Bloomberg says that the rate of return on assets for US banks is down by 35 per cent since 2007, partly because of the higher cost of capital.

UK banks have fared less well with profits across the sector down by 65 per cent over the past decade, says the FT. RBS looks set to record a tenth consecutive year of losses.

£71.4 billion

Tax take for the UK exchequer from the financial services sector last year, says the BBC.

This shows the continuing reliance of the UK economy on its financial services sector, especially banking which accounts for £34.2 billion of the total and is one of few industries with a trade surplus.

121 months

The time elapsed – it translates to ten years and one month – since the Bank of England last raised interest rates. It was July 2007, just before the crash hit.

Some 101 months ago, the base rate hit a record low of 0.5 per cent. It remained there until last August when a new all-time low of 0.25 per cent was set as the central bank sought to counter an expected Brexit slowdown.

In the US, rates have been increased a few times since December 2015 but they remain very low by historical standards.

£200 billion

Household "unsecured" debt – borrowing that isn't secured against an asset like a car, personal loans or credit card spending – as of this June, says the Guardian.

It's the first time unsecured lending has been this high since 2007. Things are much safer than they were, not least because banks have bigger reserves, but the size of the debt means some commentators are worried about a new financial crash.

It's interesting reading many of the retrospectives about the crisis, as many ask: what has changed?

Howard Davies, the first Chairman of the Financial Services Authority and now Chairman of the Royal Bank of Scotland, notes in The Guardian that not enough has changed. Whilst banks have a tougher regulatory regime and have increased the size and quality of their capital reserves, he thinks the issue still lies with too much inconsistency between national state regulators:

A recent study by the Financial Stability Institute, established by the Bank for International Settlements and the Basel committee on banking supervision, concludes that ... of the 79 countries, 39 still operate a three-way sectoral breakdown, and 23 have integrated agencies (nine of which double up as the monetary authority). Nine others have two agencies divided along sectoral lines, and eight have chosen a so-called Twin Peaks system, with one agency handling capital-market regulation and the other overseeing business conduct.

He argues that regulatory diversity of financial markets creates weaknesses and that the Financial Stability Board should try to harmonise these regimes.

Meantime McKinsey also produced a 16-page report asking what’s changed since the crisis hit.

The biggest change is a move against globalisation. Before the crisis, everyone was talking globalisation. I remember the G8 Summit where one protester held up a sign saying Join The Worldwide Movement Against Globalisation. There was some irony there but certainly, globalisation has moved off the agenda in the past decade.

The big global, universal banks are now the big, global, corporate banks, and the move by the likes of Citibank, HSBC and others to have branches in every city has disappeared. Operations in every country to support corporate clients yes; retail operations in every country, no.

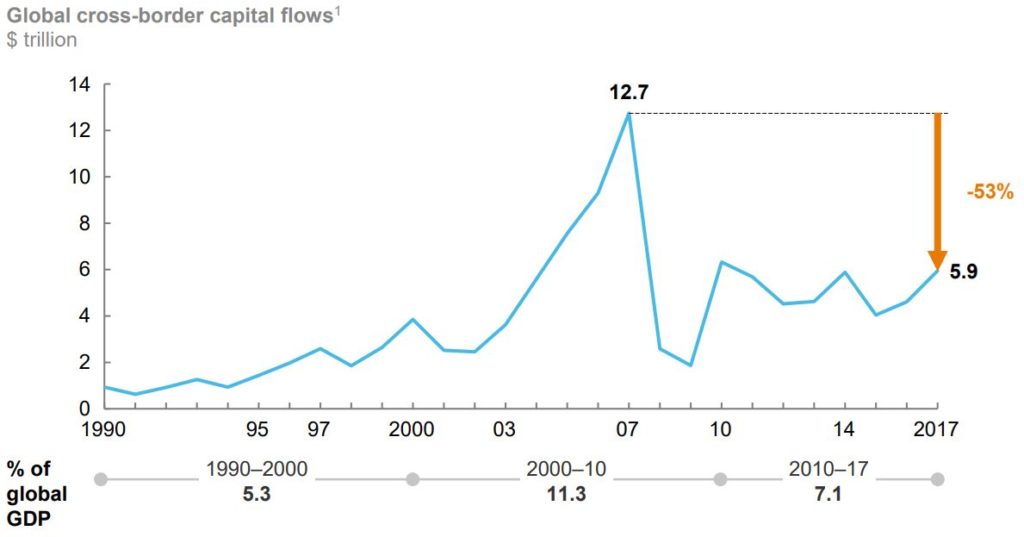

This is well illustrated by this chart from the McKinsey report that shows cross-border capital flows have dropped by half since 2008.

In other words, the interconnectivity of global markets have disconnected. That’s why Europe had such issues with sovereign debt, and why countries around the world are finding themselves more and more isolated. In fact, the biggest illustration of anti-globalisation is Donald Trump and his America First stance which, whether you like it or not, proves immensely popular with the average Main Street American.

Meantime, China with its Belt-and-Road policy is turning into the new global superpower. Therefore, it’s interesting to read the opening lines of McKinsey’s report:

Confounding expectations, the combined global debt of governments, nonfinancial corporations, and households has grown by $72 trillion since the end of 2007. The increase is smaller but still pronounced when measured relative to GDP. Underneath that headline number are important differences in who has borrowed and the sources and types of debt outstanding. Governments in advanced economies have borrowed heavily, as have nonfinancial companies around the world. China alone accounts for more than one-third of global debt growth since the crisis. Its total debt has increased by more than five times over the past decade to reach $29.6 trillion by mid-2017. Its debt has gone from 145 percent of GDP in 2007, in line with other developing countries, to 256 percent in 2017.

Debt drives growth drives risk drives losses drives austerity (UK buzzword) drives saving drives contraction drives rethink drives debt drives growth drives …

You get it, it’s a cyclical thing.

That’s why when Jamie Dimon’s daughter asked him what’s a financial crisis? he answered something that happens around every seven years.

This is why people don’t trust banks, because banks create problems in the economy and control our lives. Banks claim their unique status is that they’re trusted, but they’re not. They’re trusted as safe stores of money, due to the insurance scheme from the government that protects money in a bank account by law, but they’re not trusted as companies.

A recent YouGov poll of British consumers found that 66% of adults in Britain do not have faith in banks to work in the best interest of society, while 72% believe banks should have faced more severe penalties for their role in the 2008 crash. A further 63% think banks will create another financial crisis.

Of course, they will. It’s not a case of if but when.

Luckily most crises are small and nothing like 2008, which was a Global Financial Crisis on a par with 1929 when the Great Recession hit. When will there be another? My view six years ago was 2045 … maybe or maybe not. We shall see.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...