I’ve tracked Wirecard for some years, as they were the bank partner that allowed Ollie Purdue to drop out of university at 21 years old to launch a bank called Loot. Wirecard basically offer the platform of many other firms to offer full banking services across Europe. Based in Germany, their clients include many FinTech names of note including Revolut, Curve, Funding Circle and Pockit.

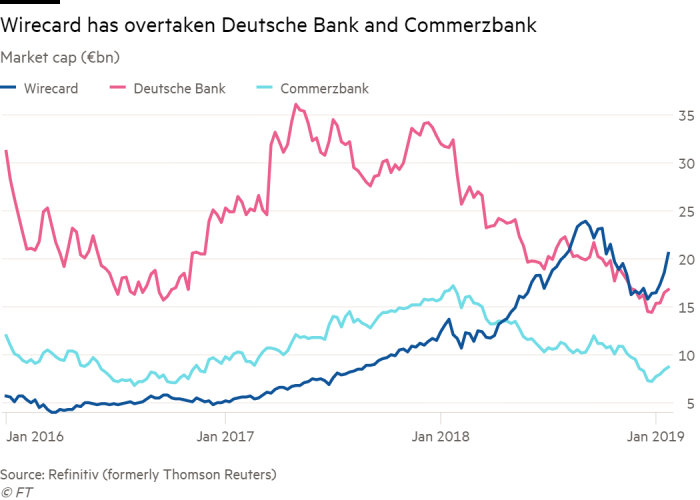

A great company to be around and one of the highest valued financial firms in Europe and Germany.

So, I was disappointed to see the investigations by The Financial Times into their accounting practices. In fact, The Financial Times determined to focus upon investigative journalism around the company because, having found issues, they aren’t letting them go.

The first reports of an accounting scandal at the firm rose a year ago, when a whistleblower briefed The Financial Times on what was happening:

The whistleblower who briefed The Financial Times on the document was motivated to do so, the person said, out of a concern that no action appeared to have been taken over potentially criminal acts inside a company presenting itself as a blue-chip financial institution.

What were they doing?

A practice known as “round tripping”: a lump of money would leave the bank Wirecard owns in Germany, show its face on the balance sheet of a dormant subsidiary in Hong Kong, depart to sit momentarily in the books of an external “customer”, then travel back to Wirecard in India, where it would look to local auditors like legitimate business revenue. In isolation, Mr Kurniawan’s scheme might have appeared to be the act of a rogue employee in the provincial outpost of a little known financial group. But the account of what happened, in a preliminary report on the investigation by one of Asia’s most eminent legal firms, indicated it was part of a pattern of book-padding across Wirecard’s Asian operations over several years.

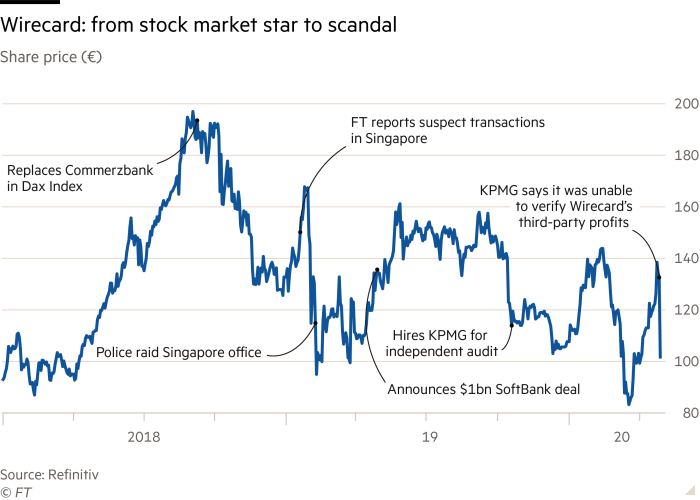

These reports led to an investigation into Wirecard’s business practices by BaFin the German regulator, and a raid on Wirecard’s offices by Singapore police.

Wirecard hired law firm Rajah & Tann to investigate what was going on and their report in March 2019 acknowledged accounting oversights and potential criminal liability among some Singapore staff, but didn't find evidence of criminal activity linked to Wirecard's German headquarters.

That didn’t satisfy The Financial Times who continued their investigations and reported, in October 2019:

A focal point of The Financial Times inquiries into Wirecard is one of these partner companies, a Dubai-based intermediary called Al Alam Solutions, which documents indicate contributed half of the German company’s worldwide profits in 2016.

Wirecard staff have described Al Alam as a “third-party acquirer”, payments jargon for a business licensed by the big payment networks, such as Visa and Mastercard, to help retailers accept credit card transactions. Al Alam was purportedly the spider at the heart of an international web, processing vast sums for 34 of Wirecard’s most important and lucrative clients in the US, Europe, Middle East, Russia and Japan.

Yet when The Financial Times visited Al Alam’s Dubai office this year it became clear this was a threadbare operation. A former employee told The Financial Times it had just six or seven staff.

Neither Visa nor Mastercard have any record of a relationship with Al Alam, deepening the mystery of why Wirecard would refer business to the partner company, given the German fintech group already has Wirecard Processing, its own payment processing subsidiary employing scores of staff, nearby in Dubai.

Internal financial reports from 2016 and 2017, shared between members of Wirecard’s finance team and obtained by The Financial Times, detail the business which has supposedly flowed through Al Alam. The documents record about €350m of payments from 34 key clients as passing through Al Alam, on behalf of Wirecard, each month during the period.

Yet there are strong indications — likely to attract attention from auditors and regulators — that much of the payment processing attributed to these 34 clients could not have taken place.

That does sound dodgy. Combine that with the accounting issues in Asia, and no wonder The Financial Times investigated and sought facts.

Meantime, it’s led to a real spat between The Financial Times and Wirecard.

Wirecard has claimed that Financial Times reporters have facilitated market manipulation in collusion with short sellers. These allegations have been widely circulated in the German media and are the subject of a legal complaint in Germany, an investigation by BaFin, the German financial regulator, and a probe by prosecutors in Munich.

Wirecard not only issued a rebuttal, but hired KPMG to prove that The Financial Times investigations were wrong.

Last week, KPMG issued their report and, oh dear, they didn’t clear Wirecard of wrong-doing. In fact, they’ve made it worse, according to The Financial Times:

KPMG’s 74-page report has highlighted weaknesses in record-keeping at a regulated financial institution and raised new issues about the group’s accounting.

For instance, KPMG’s report revealed Wirecard’s senior managers did not record minutes when holding executive board meetings, and they did not sign a so-called declaration of completeness, stating that anything relevant to KPMG’s inquiry was fully disclosed.

KPMG reported some essential documents for its review arrived at the last minute, while many never arrived. Among the desired but absent information: original bank records detailing €1bn of payments.

A trustee in charge of key bank accounts had quit shortly after the special audit was launched, the report said. The so-called escrow agent terminated the relationship in late 2019, then did not co-operate in the audit afterwards, creating an obstacle for KPMG.

In terms of the accounting, while KPMG found no evidence for manipulation, it cast doubts over several areas: how Wirecard calculated its cash reserves; how it booked the revenue generated by third-party business partners; about its know-your-customer procedures; its risk management; and about the willingness of staff to co-operate with KPMG.

‘Unable to fully comprehend’ accounting

At the heart of the report was the question of third-party business. Wirecard is licensed by the big payment networks, such as Visa and Mastercard, to help retailers accept credit card transactions. When it lacks a licence in a particular country, Wirecard uses a third-party payment processor to handle the transactions on its behalf.

Wirecard had dismissed Financial Times reports that three such partners were at times responsible for half of the group’s sales and most of its profits. KPMG said three partners had in fact “comprised the major part” of Wirecard’s operating profit between 2016 and 2018, but it was not able to offer an opinion on whether the business was genuine: verification attempts “proved to be impossible, as we were not given access to the relevant data for the investigation period”, the report said.

The report said KPMG could not confirm “that the sales revenues exist and are correct in terms of their amount, nor can it make any statement that the sales revenues do not exist and are incorrect in terms of their amount”.

The report also revealed a contradiction between the level of knowledge claimed about the underlying clients. Wirecard “would neither track nor monitor these Know-Your-Customer compliance checks carried out” by its partners, the report said, a vital requirement under rules to prevent money laundering. The relationship was arm’s length and the third parties with the data did not provide it.

Yet when it came to accounting for the activity, Wirecard treated the third parties as an extension of its own business. Their sales were counted as its sales, their costs as its costs. The validity of Wirecard’s published accounts was not within the scope of KPMG’s remit, but the report questioned the approach. “We were unable to fully comprehend Wirecard’s ‘gross accounting’ of revenue generated with [third-party acquiring partners],” wrote KPMG, pointing out that it did not receive the necessary documents to do so.

When KPMG requested minutes of quarterly meetings between the German company and its third-party business partners, Wirecard wrote that such minutes were not taken in 2016 and 2017. However, on April 23, Wirecard’s accountant EY handed over the minutes Wirecard had said did not exist.

Whose cash?

The auditors also took issue with Wirecard’s practice of counting money held in escrow accounts as cash that it can readily use — an issue The Financial Times reported about in December. “There are arguments against Wirecard’s accounting of escrow accounts as cash or cash equivalents during the investigation period of 2016 to 2018,” wrote KPMG, arguing that they might not have met key requirements of IFRS accounting standards. Wirecard, the report said, provided KPMG with an opinion from a separate advisory firm stating that the approach to cash was appropriate.

Tut-tut. Wirecard put KPMG’s report in a completely different light of course:

Wirecard AG was handed the report on the special investigation by the auditing company KPMG in the early morning of April 28, 2020. It will be published at https://www.wirecard.com/transparency as soon as possible.

No incriminating evidence was found for the publicly raised accusations of balance sheet manipulation. In all four areas of the audit - third-party partner business (TPA) and Merchant Cash Advance (MCA) / Digital Lending as well as the business activities in India and Singapore - no substantial findings were found which would have led to a need for corrections to the annual financial statements for the investigation period 2016, 2017 and 2018.

However, in their latest article, The Financial Times makes clear that Wirecard is running a network of payments processors which actually revolves around just three firms:

In November [Wirecard] told investors that it worked with around 100 acquirers in 60 countries. KPMG’s report said that just three “third-party acquiring-partners” were responsible for “the vast majority of sales revenues generated” at the three Wirecard subsidiaries. KPMG also said that, before the allocation of central costs, those three units accounted for the “lion’s share” of Wirecard’s operating profit between 2016 and 2018, which totalled €985m. In those years Wirecard reported group sales of €4.5bn generated from processing €278bn of payments, indicating that the three partners were responsible for tens of billions of euros worth of transactions.

The KPMG report does not name the partners, but past FT reporting has identified these as: Al Alam Solutions, based in a largely unmanned office suite in Dubai; PayEasy Solutions, which shares an office with a Manila tour bus company in the Philippines; and Senjo, part of a Singapore payments group. All have denied wrongdoing. KPMG expressed doubts about whether the risks associated with so much business being conducted through these partners was properly disclosed to shareholders.

All in all the result is that these activities have led to Wirecard’s Chairman stepping down at the start of 2020, and their share price halving from its peak.

I will watch this spat closely as it develops further as it is not often you have a FinTech poster child on media trial.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...