We're about to take an Easter holiday and so I thought I would leave you with food for thought until Tuesday.

There are some fascinating ideas floating around about this crisis over the last six months: from nationalise all banks to hang all bankers; from the collapse of capitalism to the collapse of the world; from the end of America and the rise of China to the end of China and the rebirth of America …

You name it and you can find an answer to suit your question.

Will banks ever be trusted again?

Will the world allow leverage to be used in the future?

Should we close down or just regulate OTC derivatives?

Will clearing and settlement be the answer?

Should we create a new global supervisory body?

Can banks pay multimillion bonuses and be called sane?

And so the debate rages on … and on … and on.

I sometimes engage with this debate but - as I’m not an economist, politician, accountant or regulator - it is more with a sense of observation than engagement.

And there are two articles that were interesting to observe this week which really caught my eye.

The first is in the launch edition of Wired Magazine for the UK.

Wired has been a great magazine and future technology bible for Americans since its launch back in 1993 … amazing that it took over a decade and half to make it over here, but then Conde Nast has taken over so that’s maybe why.

The first UK issue has some specific UK content, such as an in-depth report on the BBC’s iPlayer’s success thanks to ex-Kazaa innovator Anthony Rose’s arrival in September 2007.

If you weren’t aware how successful the iPlayer has been, Version 1.0 was launched in December 2007 and by August 2008 it soaked up 20% of the UK’s total available bandwidth.

By its first anniversary, 41 million requests to view programmes are coming in every month making it the third most popular website in the UK, behind Google and Microsoft, with 19 million regular visitors compared to 3.5 million for the BBC website back in 2000.

It's already on Version 2.0 and Version 3.0 is soon to launch.

Anyways, buy the magazine if you want to read that stuff.

What jumped out for me is a repurposed article from the US Wired Magazine that I’d missed …

Strange that isn’t it?

It begs the question: 'is paper better than electronic for reading?' which is another story as the Boston Globe and Chicago Sun Times die their death …

Sorry, I diverse.

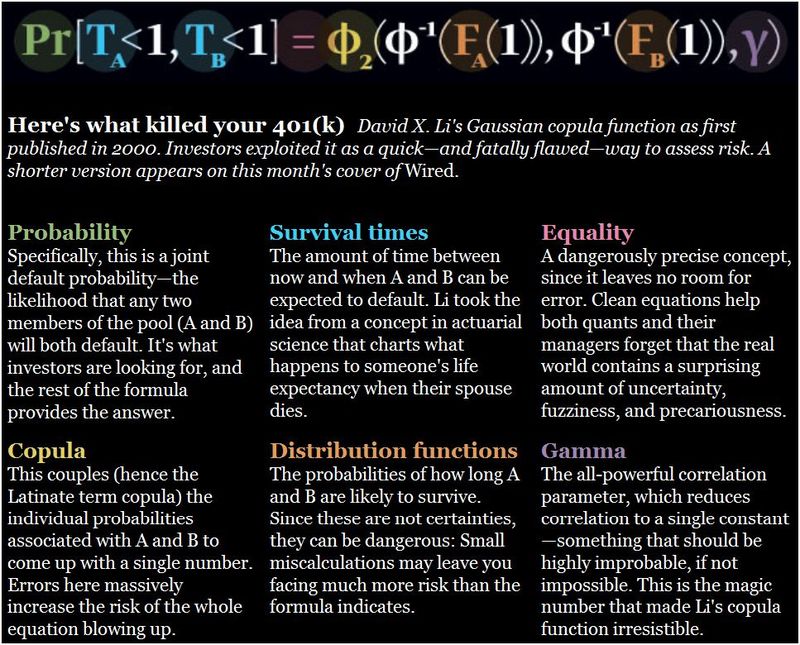

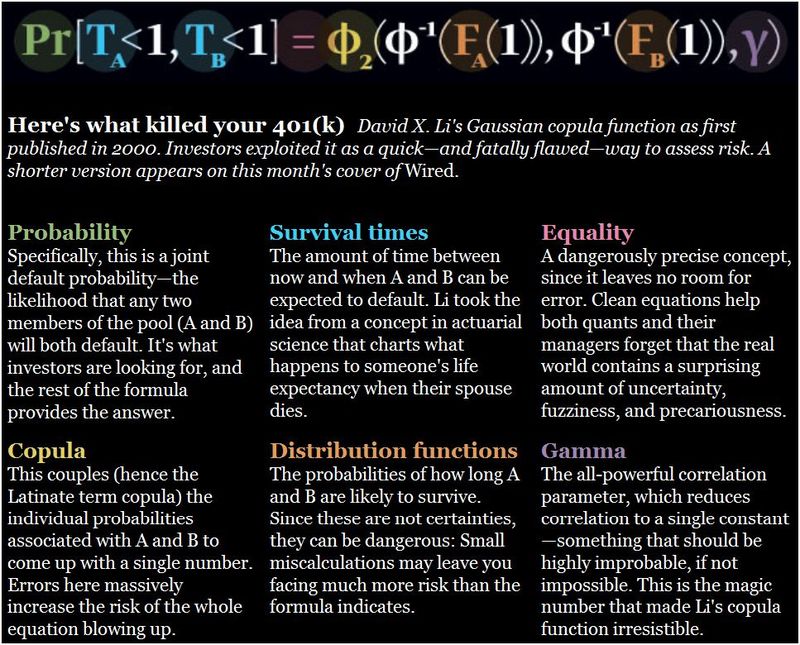

The Wired article is entitled: "Recipe for Disaster: The Formula That Killed Wall Street", and talks about how a young quant analyst at JP Morgan, David X. Li, came up with the formula for de-risking mortgage derivatives in the credit default swaps (CDS) markets and is now the man to blame for this crisis.

Now there have been many names proposed as the instigators of the credit crisis from Alan Greenspan to David Bowie, but David X. Li?

The opening paragraph of the Wired article puts this in context:

“A year ago, it was hardly unthinkable that a math wizard like David X. Li might someday earn a Nobel Prize.

“After all, financial economists—even Wall Street quants—have received the Nobel in economics before, and Li's work on measuring risk has had more impact, more quickly, than previous Nobel Prize-winning contributions to the field.

“Today, though, as dazed bankers, politicians, regulators, and investors survey the wreckage of the biggest financial meltdown since the Great Depression, Li is probably thankful he still has a job in finance at all.

“Not that his achievement should be dismissed.

“He took a notoriously tough nut—determining correlation, or how seemingly disparate events are related—and cracked it wide open with a simple and elegant mathematical formula, one that would become ubiquitous in finance worldwide.”

So what went wrong?

Well, here’s the formula (double-click to see a big version):

This formula, which is known as a “Gaussian copula function”, was published in The Journal of Fixed Income in 2000 in an article entitled: "On Default Correlation: A Copula Function Approach" (you can download it here).

The formula modelled risk of credit defaults in a way that did not rely on historical data, and became the standard formula for calculating risks in the CDS markets.

The problem with it, as it turned out, is that it was fatally flawed exactly because it did not use real-world data. It had no correlation with the underlying assets, mortgages, and therefore did not work.

However, regulators, ratings agencies, the bond markets and all the trading rooms of the world missed this key feature because it looked so perfect, and used Li’s formula to blow up the CDS market from a mere $920 billion in 2001 to a $62 trillion market by the end of 2007.

And that blow up did just that … blew up.

So now everyone blames poor Mr. Li for this crisis.

Not so, but Mr. Li’s formula certainly is to blame.

So, there we go. End of story.

Or is it?

The fact is that the explosion has meant a complete degeneration of trust in the financial system and markets as governments haemorrhage budgets to try to fix the issues and consumers wonder how much their houses aren’t worth.

So that led me to another magazine, Prospect, which this month headlines with an article entitled: “After Capitalism” by Geoff Mulgan, a Director of the Young Foundation.

The sub-heading states: “The era of transition that we are entering will be disruptive—but it may bring a world where markets are servants, not masters”, and Mr. Mulgan talks about a wide range of issues and areas behind this crisis and its outcome.

One part really intrigued me:

“To find insights into how the current crisis might connect to these longer-term trends we need to look not to Marx, Keynes or Hayek but to the work of Carlota Perez, a Venezuelan economist whose writings are attracting growing attention.

“Perez is a scholar of the long-term patterns of technological change.

“In Perez’s account economic cycles begin with the emergence of new technologies and infrastructures that promise great wealth; these then fuel frenzies of speculative investment, with dramatic rises in stock and other prices.

“During these phases finance is in the ascendant and laissez faire policies become the norm.

“The booms are then followed by dramatic crashes, whether in 1797, 1847, 1893, 1929 or 2008.

“After these crashes, and periods of turmoil, the potential of the new technologies and infrastructures is eventually realised, but only once new institutions come into being which are better aligned with the characteristics of the new economy.

“Once that has happened, economies then go through surges of growth as well as social progress, like the belle époque or the post-war miracle.”

So I started reading Perez’s work and find myself drawn into this discussion because it gets interesting.

The thesis is one that structures are destroyed by technology and then re-energised into new forms.

In an interview with Strategy and Business, Perez explains the basics:

Strategy & Business: “Tell us more about these previous technological revolutions.”

Perez: “There have been five since the late 18th century. Each lasted 45 to 60 years. They each produced a great surge of development: growth, employment, new products, new industries, and — most important of all — new infrastructures for carrying goods, energy, people, and information farther, faster, and more cheaply. And while they were extremely different technologically, each revolution followed a similar pattern of phases and changing business climates.”

Strategy & Business: “And they were…?”

Perez: “The first surge was the classic Industrial Revolution that started in 1771. It brought mechanization, factories, and canals. The second, centred in Victorian England, began around 1829: the age of steam engines, coal, and iron railways. The third was the age of steel and heavy engineering. Civil, electrical, chemical, and naval engineering developed impetuously then.”

Strategy & Business: “When did that surge start?”

Perez: “Around the mid-1870s.

“That was when cheap Bessemer steel made possible transcontinental railways, major tunnels and bridges, and rapid steamship lines. Those, along with telegraphy, led to the first great globalization — which, by the way, was coordinated by the British Central Bank and the City of London.

“With those technologies, Argentina, Australia, and others in the Southern Hemisphere could send grain and meat in refrigerated ships to the northern winter markets.

“In the fourth surge, which started with Henry Ford’s Model T in 1908, the centre of gravity shifted to America. This was the age of oil, mass production, and the automobile.

“Our present, fifth, surge, the age of information technology and telecommunications, began in 1971 with Intel’s microprocessor.

“If the historical pattern holds, this surge still has 20 to 30 years left to realize its potential.

“I could guess that the next wave will involve biotechnology, bioelectronics, nanotechnology, and new materials. But those are still in gestation, just like the transistor of the 1950s represented the microprocessor in gestation.”

The Economist sums up Perez's approach in financial innovations:

“Carlota Perez, a Venezuelan economist, thinks that each new industrial

technology favours its own sort of financing. Local banks grew up to

raise capital for the small companies created in Britain’s industrial

revolution; joint-stock companies thrived when businessmen needed to

finance the railways in the 19th century; industrial banks backed new

continental European industries; consumer finance helped Americans buy

cars and fridges in the early 20th century. Ms Perez links each

financial innovation to its own booms and busts.”

I totally buy into the idea that technological revolutions create commercial revolutions create financial revolutions create societal revolutions create political revolutions.

Without even knowing of Perez's work, I picked up on this when publishing a paper three years ago on how commercial revolutions create payments revolutions.

That is exactly what we are seeing on the back of the networked world.

In fact, although Perez picks up on biotech and life sciences, which will be a revolution, the ramifactions of the Wintel, Google, Facebook and related net-based issues have yet to be identified and no-one knows the outcome yet.

But the discussions I'm writing around the future of banking start to point the way to a vision.

Are we there yet?

No.

And no-one has yet outlined an economic, societal or political vision or an outcome.

My own take would be one based upon community collaboration through citizens’ worldwide providing knowledge, skills and expertise through a globally connected pool of talent.

What would that be?

Collaborism?

More soon …

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...