There’s the classic old joke about the European dream being a place where the police are English, the chefs are Italian, the car mechanics are German, the lovers are French and the bankers are all Swiss. The nightmare is that it is a place where the police are German, the chefs are English, the car mechanics are French, the lovers are Swiss and the bankers are Italians.

It seems that the nightmare is coming true, although the basket case is Greece and the bankers are German.

Last week’s surprising comments from German Chancellor Angela Merkel that “the euro is in danger” and “if the euro fails, Europe fails” sent shudders across the world’s markets, and probably made Brussels shake with rage.

But the Germans are shaking with rage. After Nicolas Sarkozy was rumoured to threaten Merkel with France’s withdrawal from the euro if she didn’t step up to the plate and support a Greek bailout, Germany’s citizens have been demonstrating their rage by printing deutsche marks whilst the national newspaper, Bild, is stirring anger towards the EU and the Greeks in particular with headlines such as:

- "How much more do we have to pump into this country?" April 26th

- "Why are we paying the luxury pensions of the Greeks?" April 27th

- "Greeks ready to cut back? They would rather strike!" April 28th

As I talk to German colleagues, they refer to Greece as the Golden Fleece and that they aren’t paying bills in Greek restaurants because they’ve prepaid to 2020.

All of this puts a huge strain on the European Union, in its fragile 53rd year of unity, particularly as Spain, Italy and Portugal are considered to be on a par with Greece by many, forming a Southern European Union called the PIGS [Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain].

It raises a key question in my mind, and I’m sure all of the bankers I deal with: if the euro fails, what happens to the monetary union of banks, the Financial Services Action Plan and all those bank and insurance directives like Solvency II, MiFID and the PSD?

What happens to Chi-X, SEPA, the EBA and the rest?

In order to answer this question, you have to look at two key areas. First, is the economic and monetary union (EMU) broken? Second, if it is, do we throw away the eighteen years of change introduced by the agreement to launch the euro when the Maastricht Treaty was signed in February 1992?

Let’s take the first question: is the EMU broken?

We asked this question in 2005, when the French and Dutch threw out the EU Treaty. Answer: it is political union that they were rejecting, not economic union. Note: even with their rejection, and the Irish no vote, the Treaty became the Lisbon Treaty in 2010 regardless of such resistance. In other words, in the interests of the long-term vision of Europe, Europe wins.

Equally, America has taken years to gain its United status, starting with a nation of disparate states that had far less history than those of Europe. Their Union was easier in comparison, and that still took years, so Europe’s union will take time and will face many more tests.

But this is the greatest test so far.

The size of this test should not be underestimated as it is the first time that we are seeing an economic union, resulting in a cascading effect upon money and politics. Historically, the tests for Europe have been mainly about how much power is ceded to Brussels. This test is showing the inter-relationship between economies and Germany’s anguish is that if they are to keep the vision of Europe in harmony, then they have to pay for it.

Therefore, returning to the rejection of the European constitution, that was a political rejection and when a country has an economic crisis, the monetary union means that other nations pay and, as a result, that political will is tested when one nation's tax dollars are taken to pay for another nation's debts.

That is why this challenge is so much greater than any before, because it is testing the political will of citizens, not just their ability to trade and compete.

The core issue though, is that it is not just the Greek economy and Greece that would leave the Union if they were allowed to fail. It is the Union.

Should the Greek economy fail to honour their government bonds due to being economically bankrupt, the ratings agencies and banks would downgrade Spain, Portugal and Italy, and there would be a spiral effect. This means the European Union breaks apart.

That is why the Greek failure option is unpalatable ... but is the alternative palatable?

Why do we need a European Union?

Answer: Europe needs to be a Union to maintain its drive to be a regional superpower, and competitive commercially and economically with China and America. There’s the rub. If Europe fails, then the UK, Germany and France fail, as parity to compete internationally and intraregion becomes far more difficult.

This is why Greece needs the bailout and why Germans are paying.

It does not help Angela Merkel maintain her status or power hold in Germany – her popularity is sinking faster than the Titanic – but if Greece fails, it is felt that Europe may fail too. And that is not an option seen to be agreeable today.

Also, nations have been bailed out already.

Two years ago, Spanish banks received over €50 billion worth of ‘aid’, in the form of mortgage-backed securities with the European Central Bank (ECB), when they faced a property meltdown.

Did the Germans wail out about that bail out?

No.

Why?

Because it wasn’t on the front page of the Bild.

That bail out was smaller and less obvious, so no-one really noticed.

The Greek bailout is a bit bigger – €110 billion – admittedly, but it is supported by the IMF and is necessary for Europe’s future. ‘nuff said, although if you want to know more, Robert J Samuelson in the Washington Post provides a particularly good overview of why Europe needs to support Greece.

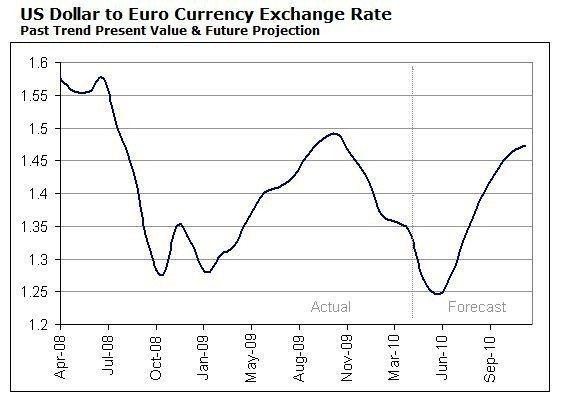

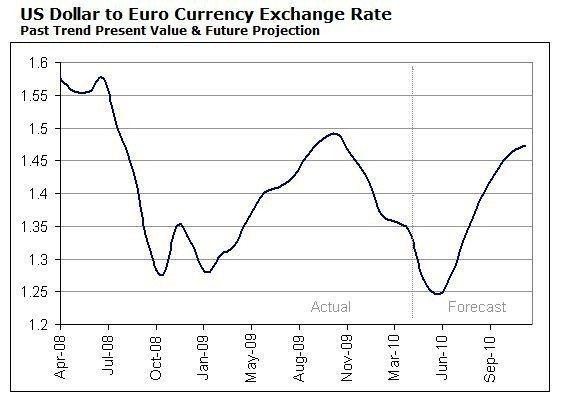

My summation is that Europe will survive this crisis, the euro will stay and the currently ridiculous pricing of US$1.24 to the euro will reverse within the next month or so, as forecasted by most economists.

But let’s look at the worst case scenario: what do we do if the euro does fail? Does it mean we unravel all we’ve done to date?

This is the second and, in some ways, more important question: is there a backup plan?

OK, if the Eurozone breaks apart, then it matters ... but it will not throw away all that has been built to date.

The banks will still want to use cross-border instruments that work. They will just bring back a margin to represent those cross-border movements whilst maintaining the efficiency of the infrastructure that has been built.

As Werner Steinmuller, Head of Global Transaction Services of Deutsche Bank, stated when we researched the Payment Services Directive (PSD) and the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) last year:

Deutsche Bank is in a comfortable situation. We spent quite a sizable amount on SEPA infrastructure and have a brand new system that is extremely capable of doing this that is also highly scalable. Others have not made this investment so this gives us a price advantage. We have built some conversion solutions for handling old volumes and now can run both old instruments and the new SEPA instruments so, if SEPA is coming, we are extremely well positioned. If SEPA fails, I can write off the investments and still win.

In other words, the SEPA process has forced the banks to build new infrastructure, new systems and new efficiencies in transaction processing. That will stay. It does not go away if the euro goes away, as the new infrastructure is designed to handle efficient transactions, not euro payments.

So if we look at SEPA Credit Transfers and Direct Debits, the Euro Banking Association (EBA) and STEP2 ... it will all stay. The EBA will be a private consortium to operate efficient systems, rather than a government initiative to create efficiency, and it will stay. There will be a charge for this, and a charge that could provide a substantial return to the banks that created this infrastructure, but it will not go away.

The same will be true for Chi-X, and the capabilities electronic trading platforms have introduced into the European equities markets. Sure, some countries may want to block and reverse policies in these areas – Spain? – but the process of regional investing is unstoppable now. Goldmans, Merrill, BarCap and co, won’t want to see this go away, so it will remain.

Bottom-line: the efficiency of European payments and investing is in the interest of banks, corporates and institutions today, not just governments and policymakers.

So, if the euro fails, my answer is that the all the investment made by the financial markets in efficient systems will stay.

It will just be at a profit rather than a regulation.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...