After the bank reporting season in the UK last week, the most notable row that has emerged – alongside bonuses and a lack of lending – is the lack of taxes banks pay.

Banks are remarkably adept at being tax efficient – or should we say, tax avoiders – and this has been known for years. It is tolerated by governments as the taxes they avoid are all legitimate accounting techniques to minimise corporation tax whilst, on the other hand, they are big payers of national insurance contributions, pay-as-you-earn and other employee earnings-related taxes.

This conundrum puts governments in a bind: if they clamp down too hard on their banks, then they lose a possibly major chunk of tax revenues. However, by not clamping down on the banks, they lose a major chunk of tax revenues anyway.

This dilemma is the one facing the UK government in particular, as they see a dysfunctional banking system that they want to tax heavily but they know that, if they do, the banks will leave.

This was clearly demonstrated by the often mooted rumour about HSBC relocating to Hong Kong – that’s been around since Michael Geoghegan’s office moved there two years ago, although it’s interesting that new CEO Stuart Gulliver has clearly said the office should be in London – and Barclays to New York.

Such sabre-rattling frightens the likes of George Osborne and Vince Cable, but does it frighten the likes of Mervyn King and Sir John Vickers?

Probably not, as Mervyn King has been quite outspoken over the weekend about bankers bonuses and poor treatment of customers whilst promoting the idea that banks should be split between boring banking – retail and commercial – and casino banking – investments. A view that appears to be increasingly endorsed by Sir John Vickers, who will provide the regulatory framework for long-term bank reform later this year.

If it does go this way – higher taxes on bonuses and salaries, the forced split of proprietary trading (the casino bit of investment banking) and general restructuring, then be assured that it will mean the banks will relocate.

Not Lloyds and RBS – the government owned banks – but the big two of the big four: HSBC and Barclays.

Now, is this a big loss?

Yes and no.

It comes back to the taxation piece.

According to a report by Pricewaterhouse Coopers, banks more than pay their way in the UK economy.

The industry contributed an estimated £53.4 billion to UK government taxes in the 2009/10 financial year, accounting for 11.2% of the total UK tax take.

The figure, which excludes the 50% top rate of tax and the Bank Payroll Tax, is down by £8 billion from the previous fiscal year but the sector has overtaken North Sea oil and gas to become once again the largest payer of corporation tax in 2010.

The sector employs over one million workers which helped to generate £24.5 billion in employment taxes.

Wonderful.

That’s slightly less than the amount stated by the banks in Project Merlin’s documentation (HM Treasury published summary, pdf document), where the banks say they will “contribute a cumulative £8 billion of total tax take (covering direct and indirect sources, including the Bank Levy and VAT) in 2010 and, on the same basis, £10 billion in 2011.”

But what’s £45 billion here or there?

The real issue is that the banks can easily offset tax liabilities based upon clever accounting.

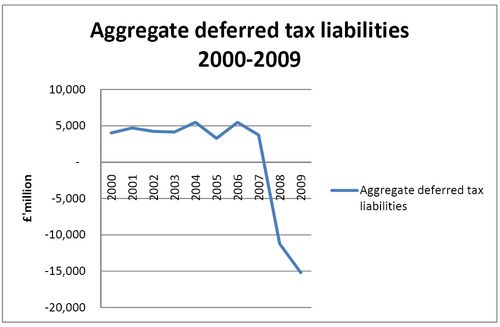

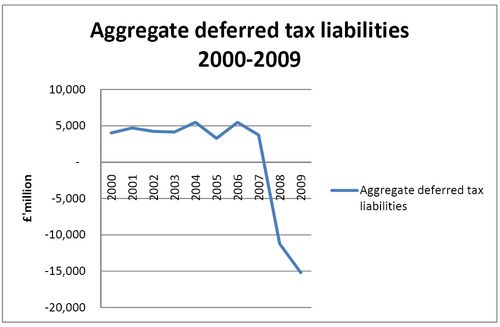

For example, leading accountant Richard Murphy writes that the UK banks received an effective subsidy of £19 billion, by writing down this amount as deferred tax liabilities due to expected losses in 2008:

“If some £19 billion in tax might not be paid as a result at some time in the future, there is an extraordinary double subsidy going on for these banks. Not only were their losses underwritten by the state in 2008 (and in most cases they still are receiving some form of state support, if only by way of asset guarantees), but they will now receive a second round of subsidy when over years to come they will offset those state subsidised losses against the profits they might now make only because they have been saved for the benefit of their shareholders by the UK government.”

So there is some issue here about tax isn’t there?

It’s one raised often by the Treasury Select Committee and, in particular, by campaigner MP Chuka Umunna who asked Bob Diamond in the last meeting how many offshore companies the bank had in global tax havens.

About 300, Bob Diamond answered.

No wonder they only managed to pay £113 million in Corporation Tax last year. That was on the back of pre-tax profits in of £11.6 billion.

Similar questions are being raised by analysts about Lloyds and HSBC.

For example, Lloyds Banking Group won’t pay any corporation tax until 2015 or after, even though it made over £2 billion in pre-tax profits.

Ian Fraser writes a good summary of the analysis of Lloyds results over on Naked Capitalism, and the point made is that creative accounting can make any bank look good.

Lloyds were buoyant about rebounding from more than £6 billion in losses in 2009 to a £2.2 billion profit in 2010 … except that the statutory profit was a loss of £320 million.

There are many definitions of profit.

Charges of £1.65 billion as the cost of integrating HBOS with Lloyds, a £500 million purse to reimburse mortgage customers for over-charging and a £365m loss on the sale of two oil-rig subsidiaries had been stripped out of the ‘profit’ figures.

There are many definitions of profit.

There is also a thing called “fair value unwind”.

In Lloyds accounts, they have a specific area relating to the HBOS acquisition representing fair value, and the “fair value unwind represents the impact on the consolidated and divisional income statements of the acquisition related balance sheet adjustments. These adjustments principally reflect the application of market based credit spreads to HBOS's lending portfolios and own debt.”

In other words, it is the write down of what was over-valued in the HBOS takeover and, as a result, higher valuations on HBOS assets and business lines since the deal was done had added £3.12 billion to Lloyds’ headline pre-tax figure.

There are many definitions of profit.

There was a further £7.9 billion of largely unidentified ‘available for sale’ assets also moved into a newly-created accounting basket of ‘held to maturity’ assets as part of the “fair value unwind”. This is a good move as such assets don’t need to be marked to market, which can also improve the accounting view.

There are many definitions of profit.

HSBC has faced similar questions about taxes from US authorities and UK activist groups, whilst Royal Bank of Scotland doesn’t have to worry about profits right now – they made a £1.1 billion loss – but they don’t have to worry about taxes either: “RBS finance director Bruce van Saun also admitted today the bank would pay no corporation tax again in 2011 as it has deferred tax assets of £6.3bn it can use up from previous losses before paying any tax.”

All in all, this new dialogue is quite concerning as transparency in bank accounting is hard – there are differences between USA and International Accounting rules for example, between GAAP and IFRS, and then there are all these complexities layered on top between mark-to-market, fair value, liabilities and impairments, on balance sheet and off balance sheet, and so on and so froth.

Which finally brings me to Basel III.

Basel III is a subject I generally try to avoid, but it has raised its ugly head this week with a report from the Matrix Group, published online by David McKibbin.

Why does this report worry me?

Checkout the management summary:

“We believe that changes in regulations for bank capital are a ‘game changer’ for the sector.

“The proposals from the Basel Committee published in December 2009 will increase the quantum of capital in the system, improve its quality, force out complexity from balance sheets and ultimately drive down ROE.

“We undertake a thorough analysis of what happens to the banks’ capital in an attempt to replicate as closely as possible the anticipated findings of the Basel Committee’s own impact study, due H2 2010.

“The results are very interesting.

“The UK banks Lloyds and HSBC are significantly impacted by the proposals.

“We see Lloyds, in particular, having a new Core Tier ratio of only 4.4% by the end of 2012.

“The fall is mainly due to the full deduction from common equity of investments in other financial institutions of £10bn (mainly insurance), which under the present FSA transition rules, is only deducted at the total capital level (not 50:50 from Tier 1and Tier 2 capital as for most other banks).

“Basel III is essentially crystallising the problem that Lloyds has been able to get away with for years of double counting the capital in other financial entities on the group balance sheet.

“We also see HSBC’s Core Tier 1 ratio falling to 6.0%, significantly below peers and in line with what we would deem to be an appropriate regulatory minimum.

“The reasons for the substantial fall in the Core Tier 1 ratio are more varied than for Lloyds and arise mainly from the deduction of negative AFS reserves, the deduction of minorities, the increase in market risk weights and the deduction of investments in other financial entities.

“For the last point, HSBC has, like Lloyds, taken advantage of the FSA transition rules currently in force and opted to deduct investments in financial entities at the total capital level rather than 50:50 from Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital.

“We believe that management may ultimately desire to raise more common equity to obtain a capital buffer and regain parity with peers.”

Be assured that bank accounting rules are under intense scrutiny, and will be more so in the future.

But no bank is going to appreciate Basel III adding layers of excess capital requirements to their already over-burdened balance sheets.

For example, take note of this quote from Karen Fawcett, Senior Managing Director and Group Head of Transaction Banking with Standard Chartered Bank (pdf of SIBOS Issues, October 2010): “If the regulations are implemented as they are currently written, we could be seeing a 2% fall in global trade and a 0.5% fall in global GDP.”

What the banks are really saying is that if Basel III is implemented as it is currently written, and if banks ever move to accounting practices where apples can be compared with apples, then global trade will decrease because the lubricants of trade – leverage and risk – will be curtailed.

Is that such a bad thing?

Blog inspired by Ian Fraser’s tweets

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...