By the early 1700s, London had established the basic mechanisms of modern finance – a central bank with the ability to stabilise monetary policy; a stock exchange to enable financing of industry and commerce; and an insurance marketplace to cover risks in business.

These capabilities were not unique however. As motioned, Antwerp had a thriving Exchange dating back to the 16th century; Hamburg, Sweden and the Netherlands all had solid central banks; and insurance had been practiced actively in all ports across Europe.

Equally, London’s financial markets had been preceded by other successes, such as the Medicis, bankers to the Borgia’s in Italy in the 15th century.

So what made London’s financial centre become so powerful?

Victory at war.

Now, if you can't be bothered reading what's below, then here's a brief five minute version of what happened from the BBC series Horrible Histories:

Meanwhile, for those who like a good read and one that's more relevant to the financial markets, read on.

Britain was a war-mongering, empire building, colonising nation and thanks to its ability to win wars over the French, Spanish and Dutch, its financial industry’s reach covered the globe from the colonised America’s in the first wave of Empire building to the Far East, Asia and India in the second wave.

From the Glorious Revolution in 1688, that saw the switch from the Stuart King Charles II to the Hanover King William III until the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, saw Britain’s rise to a dominate among European trading empires, and became the first western nation to industrialise.

The extent of economic change between 1688 and 1815 can be seen by looking at how conditions changed at home and abroad for the nation.

In 1688 England and Wales had a population of 4.9 million, and most people were engaged in agricultural work and production.

During the 18th century, Britain’s population began to trade and move abroad, with merchants sending out ships to trade with North America and the West Indies, where England had established a network of colonies.

In 1686 alone these colonies shipped goods worth over £1 million (£1 billion today) to London, including sugar, tobacco and other tropical groceries for which there was a growing consumer demand; whilst exports to the colonies consisted mainly of woollen textiles.

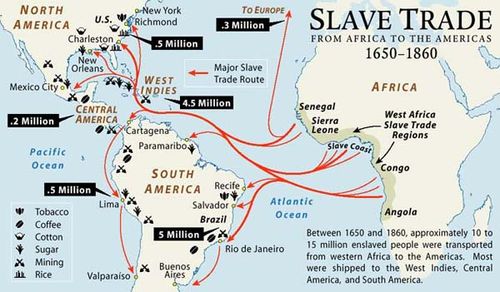

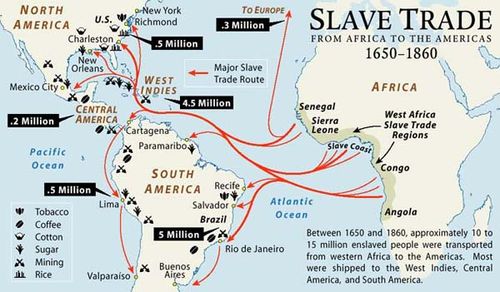

The slave trade was also flourishing, taking African labourers for work on tobacco, rice and sugar plantations in America and the West Indies, based around the activities of the Royal African Company which had its headquarters in London.

From Slaverysite.com

The Royal African Company had a monopoly on slaves until 1698 but, when this monopoly was rescinded, the British became the largest and most efficient carriers of slaves to the New World. Private merchant houses provided the capital for this business activity and Jamaica, the largest British slave colony, was also the wealthiest colony in the British Empire.

Trade and settlement also occurred in Asian waters. This was mainly based around the activities of the East India Company, a large joint-stock company based in London. The ships of the East India Company fleet traded mainly in bullion, textiles and tea with Bengal.

All of this commerce was dictated by law, the Navigation Acts, such that merchants could only trade commodities on British ships, manned by British seamen, trading between British ports and those within the empire.

Despite these developments, in 1688 Britain was still competing with the other trading empires of France, the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal for supremacy of the seas, so none of this was a done deal.

That changed with the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815, with the key victories of Trafalgar in 1805 and Waterloo in 1815.

Hence, the significance of the Nelson collection at Lloyd’s of London, for recognition of Britain’s gains at sea and the success of its marine insurance policies and structures to allow such a war to be won.

By 1815, under the growing movement of citizens from agriculture to cities to seas, the British population had increased from under 5 million in 1688 to 12 million.

During this period, many people were engaged in new work that was regular rather than seasonal, thanks to industrialisation, the growth of manufacturing and new mineral technologies, along with the arrival of factories.

Trade and colonisation had also moved forward rapidly, as evidenced by trading partnerships moving from European nations in 1700 to North America and the West Indies receiving 57% of British exports and supplying 32% of imports just 100 years later.

By 1775 Britain possessed far more land and people in the Americas than either the Dutch or the French. The East India Company's trade also flourished at this time, with greater settlement by the British in Bengal from 1765 onwards.

The loss of the thirteen mainland American colonies in the War of Independence was a major blow to British imperial strength, but Britain recovered swiftly from this disaster by acquiring additional territories from France during the war that lasted from 1793 to 1815. The new colonies included Trinidad, Tobago, St Lucia, Guyana, the Cape Colony, Mauritius, Ceylon and a number of other Indian states.

By 1815, Britain possessed a global empire that was hugely impressive in scale, and stronger in both the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, and around their shores, than that of any other European state.

All of this had occurred within basically the same protectionist trade network as in 1688, where all trade had to be made with British ships and seamen across the Empire.

Free trade, which was being much discussed by Adam Smith and Josiah Tucker, had failed to make any inroads into these economic policies.

Finally, in 1815, the defeat of Napoleon ended this stage of prolonged global conflict – war had been a notable feature of life since the 1740s, and even in 1815 there remained fears that war would break out afresh.

Throughout the struggles European rivalries and worldwide imperial competition had been inseparably connected. Dominant at last among Europe's Great Powers, Britain was firmly established by 1815 with France, Russia, Ottoman Turkey and China as one of the world's great imperial powers.

This laid the foundations for an even greater Empire under Queen Victoria, where the practices of the Bank, Exchange and insurance marketplace could stamp their authority over global financial practices.

Much of the above has been liberally reinterpreted from the BBC's History pages. Well worth reading if you have the chance and want to know more.

This is the ninth in a series about how the City of London developed its financial prowess and system.

Previous entries include:

- Part One: The Romans

- Part Two: The Vikings

- Part Three: Medieval Times

- Part Four: The Tudors

- Part Five: The Stuarts

- Part Six: The Bank of England

- Part Seven: Lloyd's of London

- Part Eight: The London Stock Exchange

- Part Nine: The 1700s

- Part Ten: The Victorians

- Part Eleven: World Wars

- Part Twelve: After World War II

- Part Thirteen: The Big Bang

- Part Fourteen: Crisis

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...