Alongside the founding of the Bank of England, the making of London as the City of Finance can be traced to two other key developments that occurred at the same time: the opening of an insurance centre and a stock exchange.

Coincidentally, all of these things happened around the same time: the Bank of England was given its Charter in 1694; Lloyd’s Coffee House, the origins of Lloyd’s of London, the insurance centre, opened in 1688; and the London Stock Exchange traces its origins to Jonathan’s Coffee House, which opened in 1698.

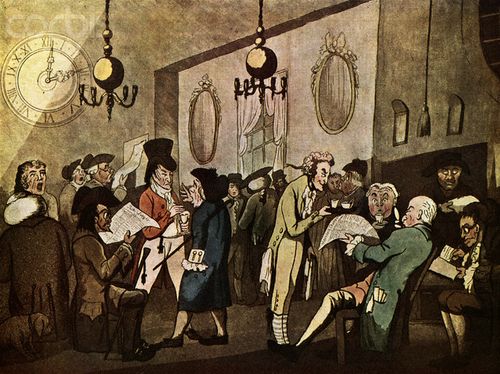

London’s coffee houses were a key source of trading and business during the post-Civil War years, and the first one was opened in 1652.

From the time of King Charles’s restoration to the throne in 1660, coffee houses proliferated until by the end of the 17th century they were numbered in hundreds.

They provided pleasant meeting places and in the City of London their popularity as places for business transactions was quickly established.

From the goldsmiths banks in the City, other trading started to take place in stocks, commodities, insurances and more, and this is how the insurance and stock exchange came about.

Lloyd’s of London

The first mention of Lloyd’s appeared in the late 1680s when an advertisement in the London Gazette offered “a reward of a guinea for information about stolen watches, claimable from Mr Edward Lloyd’s Coffee House in Tower Street”.

At this time, London’s importance as a centre of trade led to a steady increase in the demand for insurance of ships and cargoes, and Edward Lloyd’s Coffee House became the focus for marine insurance thanks to its close proximity to the docks.

Business in those days was conducted very informally. A merchant with a ship to insure would request a ‘broker’ to take the policy from one wealthy merchant to another until the risk was fully covered.

The broker’s skill lay chiefly in ensuring that policies were underwritten only by people of sufficient financial integrity who could meet their share of a claim, if need be, to the full extent of their personal fortunes.

This was a core principle of the Lloyd’s insurance markets until as recent as the 1980s, and led to the use of Names.

A Lloyd’s Name signs up for unlimited liability against insurance claims, and receives shares of profits from the broker syndicate they place their name against.

This worked until huge losses wiped out three syndicates in the 1980s due to hurricane, asbestos and other risks. For example, between 1988 and 1992, Lloyd's racked up losses of £8 billion, with each Name losing an average of £287,000 and several committing suicide as a result of being bankrupted.

Lloyd’s has since restructured, with limited liability for Names being made available and far more corporate funding. The result however is that are far fewer Names today – less than 1,500 compared with 34,000 in 1990 – and Names provided £2.4 billion of capital in 2006, under 17% of the market's capacity of £14.8 billion.

Back to Edward Lloyd’s coffee house in the 17th century.

Lloyd worked there until his death in 1713, and found a strong following amongst his clientele of ships’ captains, merchants, ship owners and others with an interest in overseas trade.

So, at a time when communications were unreliable, Lloyd gained a great reputation for trustworthy shipping news.

This was crucial to working out risks in marine insurance, in order to enable successful underwriting.

Underwriting was another practice created during this time, where the broker would take the policy and get it signed up to by Names in those days, more recently by the Names’ syndicates.

Each time someone accepted the risk, they would sign their name underneath the description of what was being insurance.

Hence, they would write under the risk, or underwrite as the term is now known as an insurance principle.

The fact that Lloyd’s Coffee House had the people wanting to place risks for their shipping and the market for people who would insurance, made this coffee house become recognised as the place for obtaining marine insurance.

In 1769, a number of Lloyd’s more reputable customers decided to break away from the original coffee house, and set up a rival establishment in nearby Popes Head Alley.

This was one of the first signs of any community of interest among underwriters and led rapidly to the establishment of a properly constituted society in the ‘New Lloyd’s Coffee House’, as it was called.

Even then, the new group found their premises too small and moved five years later, in 1774, to the Royal Exchange.

While still referred to as ‘Lloyd’s Coffee House’, it was much more like a place of business and effectively the modern Lloyd’s of London had been created.

Over the next century the society of underwriters at Lloyd’s gradually evolved with membership regulated, resulting in the incorporation of Lloyd’s by an Act of Parliament in 1871.

The Lloyd’s Act gave the Society a formal legal basis, allowing it to acquire property and make byelaws with the full authority of Parliament behind them.

A key aspect of the Lloyd’s markets is the historic use of the Lutine Bell.

The bell was carried on board the French frigate La Lutine, which surrendered to the British at Toulon in 1793.

Six years later as HMS Lutine, and carrying a cargo of gold and silver bullion, she sank off the Dutch coast.

The cargo was valued at around £1 million back then – around £1 billion today – and was insured by Lloyd’s underwriters who paid the claim in full.

Following such a major loss, there were numerous salvage attempts and the wreck yielded its most important treasure - the ship’s bell - in 1859.

It was hung in Lloyd’s Underwriting Room at the Royal Exchange and was rung when news of overdue ships arrived – one stroke for bad news and two for good.

Whenever a vessel became overdue, the bell would ring when reliable information became available and ensured that everyone with an interest in the risk became aware of the news simultaneously.

The Bell weighs 106 lbs (48 kg) and measures 18 inches (46 cm) in diameter, and has hung in four successive Underwriting Rooms: the Royal Exchange 1890s-1928; Leadenhall Street 1928-1958; Lime Street 1958-1986; and in the present Lloyd’s building since 1986.

The bell is no longer rung as the result of a vessel becoming “overdue”.

Today, the ringing of the Lutine bell is generally limited to ceremonial occasions, although in rare instances exceptions are made. For example, the bell was rung following the terrorist attacks on September 11 2001.

In 2010, 80% of Lloyd’s business comes from overseas and the market made a profit of £2.2 billion. It enjoys A+ ratings from Fitch and Standard and Poor’s and an A rating from AM Best.

More on the history of Lloyd’s can be found on their website, and attendees at Club dinners are offered guided tours of the Lloyd's building, including the Nelson collection.

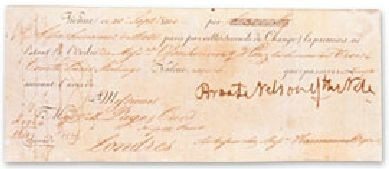

A cheque signed by Horatio Nelson drawn from Page & Creed, his banker's

This is the seventh in a series about how the City of London developed its financial prowess and system.

Previous entries include:

- Part One: The Romans

- Part Two: The Vikings

- Part Three: Medieval Times

- Part Four: The Tudors

- Part Five: The Stuarts

- Part Six: The Bank of England

- Part Seven: Lloyd's of London

- Part Eight: The London Stock Exchange

- Part Nine: The 1700s

- Part Ten: The Victorians

- Part Eleven: World Wars

- Part Twelve: After World War II

- Part Thirteen: The Big Bang

- Part Fourteen: Crisis

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...