Following the disaster of Charles II’s spending under the Stuarts, the newly reformed operations were stabilised under the new monarch, King William III.

Realising that his purse was haemorrhaging and that he couldn’t do the same as Charles, as in just default, William decided to create a new Bank that would enable funding whilst being guaranteed safe from Royal ‘confiscation’.

The idea was based upon the Bank of Amsterdam, created in 1609. Its success had been copied by others, such as the Bank of Hamburg and the Bank of Sweden, and such safe banking agreements were viewed as critical for expansion of trade and commerce.

William Paterson, a Scotsman, proposed a new bank was created with a Royal Charter as banker to the government and country, with guarantees of safety. The bank would loan £1.2 million to the Government and, in return, the subscribers would be incorporated as the Governor and Company of the Bank of England.

The subscription to the Bank’s capital was an immediate success with £300,000 raised on the first day when the subscription list was opened, and the entire £1.2 million within two weeks.

Investors were attracted by the guaranteed interest returns of 8%, and the expectation that the first joint stock bank in the country would be profitable.

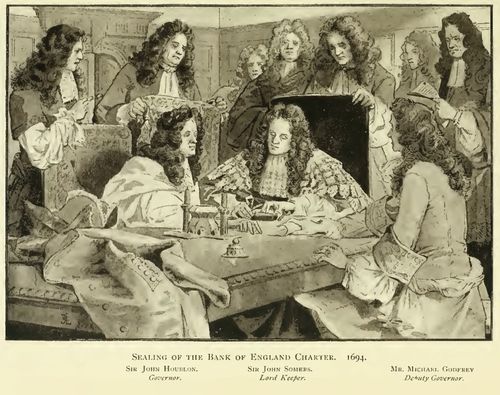

Investors of more than £500 were also given voting rights and, on 10th July, Sir John Houblon became the first Governor of the Bank of England and William Paterson, the originator of the scheme, became one of twenty-four Directors, most of whom were City merchants.

The Bank’s Charter was sealed on 27th July 1694, and the Bank opened for business with just nineteen staff at the Mercers’ Hall in Cheapside.

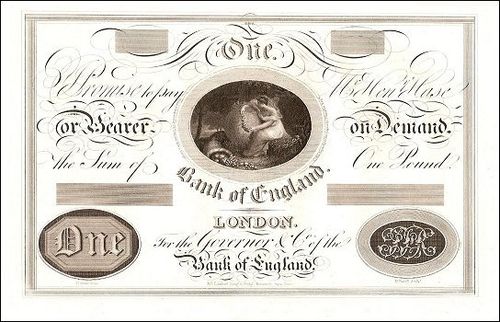

At their first meeting, the Directors considered how the Bank’s business would be conducted and, in particular, the issuance of banknotes.

Initially, they decided that deposits would be recorded in three ways. First, a passbook held by the customer would record the transaction; second, instructions from the depositor to make payment to a third party via a notation similar to the modern cheque; and third, the issuance of a running cashnote, based upon the practices of the goldsmith bankers.

These notes were common of their day already, as the goldsmiths gave receipts in exchange of cash deposited with them. These receipts became tradable in their own right, as merchants would recognise that £100 deposited with a goldsmith bank based upon these receipts would be honoured.

It was this final method that proved the most popular, and led to the introduction of the banknote as we know it today.

The notes were made out for the full amount of the deposit and endorsed by the Bank teller as and when part of the sum was cashed.

The notes were made payable to the named depositor or to the bearer, an option which allowed them to circulate as easily as cash, with a guarantee that any note could be converted back to gold upon presentation of the note to the Bank.

Three security features were quickly introduced: a medallion of Britannia, based upon the Bank’s seal; the use of highly distinctive watermarked paper; and the ‘sum block’ – a pound sign followed by the amount in white letters on a black background.

By 1725, the notes were made out in whole numbers as these were more convenient than making them out for odd sums, with the lowest denomination being £10 from 1759.

During the wars against France later that century, the drain on the Bank’s gold reserves led to the Bank revoking the promise to convert notes into gold in 1798 and, to meet the shortage of circulating currency, £1 and £2 notes were issued for the first time.

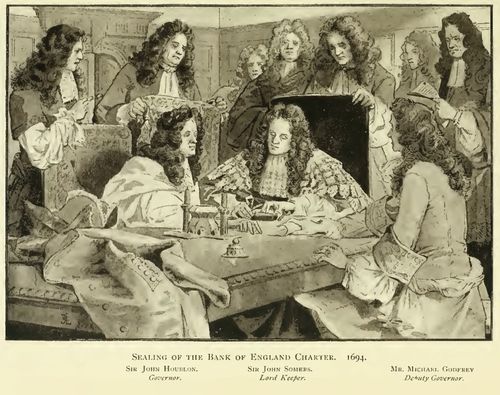

This gave the Bank its nickname: the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street - the Bank had moved to Threadneedle Street in 1734 - as, when the government ordered that paper money was no longer backed by gold, the well-known caricaturist of the period James Gillray published this cartoon.

The cartoon has the title: 'Political Ravishment, or the Old Lady of Threadneedle-Street in Danger!' and shows an elderly woman, representing the Bank and dressed in bank notes, sitting on a strong box. The Prime Minister William Pitt is shown making unwanted advances towards her, in an attempt to get to the contents of the strong box as she cries, "Rape! Ravishment!" Also worthy of note are the loan notes under his hat, which show that the Bank had been required to make large loans to the Government to finance the war against France.

It just goes to show that over two hundred years later the relationship between Government and Finance is a strong and tense one, as the government of today is still raiding the Bank’s coffers to quantitatively ease the country though the current crisis.

Meanwhile, the introduction of £1 and £2 notes brought the use of paper money to a much larger section of the population. It also brought a massive rise in forgery, as the hurriedly-produced small notes could be easily forged and most people could not tell the difference between genuine and fake ones.

As a result, the government introduced a strong deterrent and made the use of a forged banknote punishable by death or being sent to Australia, or somewhere equally as horrible.

As the number of death sentences rose, due to the increased temptation to forge £1 and £2 notes, there was an interesting protest made by the satirical cartoonist George Cruikshank.

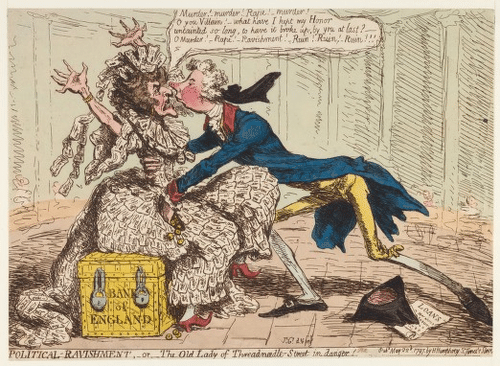

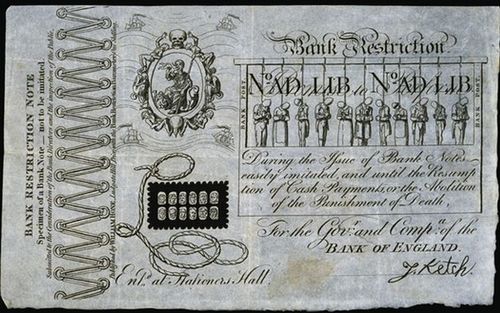

Cruikshank published this satirical but macabre banknote:

The note shows the standard features of the Bank of England's notes, but these are replaced by gruesome ornaments such as skulls, a hangman's noose, ships for transportation and a terrible Britannia gobbling infants.

The note is signed J. Ketch who was a notorious executioner in the seventeeth century due to his seriously bad aim with the axe.

Even so, forgery was still rife due to handwritten notes, notes being issued by provincial banks as well as the Bank of England, and the generally poor security features.

This led to the Bank Notes Act of 1833, which gave the Bank of England sole rights to issue banknotes as ‘legal tender’ in England and Wales, subsequently strengthened by the Bank Charter Act in 1844, which meant that no other bank could start issuing notes.

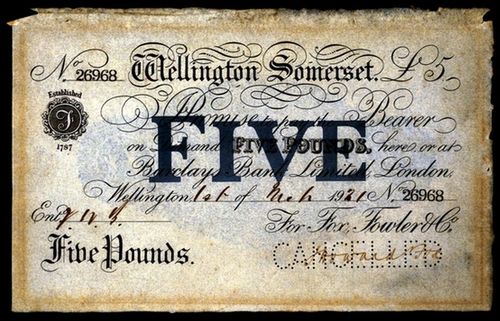

The last private banknote was issued by Fox, Fowler and Company, a Somerset bank, in 1921.

Although the 1844 Act gave the Bank the right to issue notes, it also restricted its ability to compete.

At this time, the Bank was in the same position as the other joint-stock deposit banks (today Barclays, HSBC, Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds).

This meant that, during the nineteenth century it was overtaken in size by these depositary clearing banks as they merged together and, as a result, the Bank chose not to compete directly with them but to develop its role as the central bank.

In this capacity, the Bank was charged with two key functions: to be the guardian of the gold reserve and the supplier of liquidity of last resort; functions that still exist today, although recent governments have ravished these core features somewhat, in a similar way to William Pitt.

The Bank established the concept of lender of last resort - the ultimate reserve of the banking system – during a succession of banking crises in the late nineteenth century as banks such as Overend and Gurney collapsed in 1866 and Barings in 1890.

When such events occurred, the Bank would mobilise its resources and those of the City, to ensure that a financial crisis at a single bank did not spill over into a collapse of the financial system as a whole.

It would do this by routinely using its ability to leverage the banking system's liquidity by increasing the supply of money to the banks, when no-one else could, and to set interest rates in London at what it judged to be the right level.

The First World War saw the link with gold broken again. Although an attempt was made to return to the discipline of the gold standard in 1925, it proved to be unsustainable and the gold standard was finally and completely abandoned in 1931.

Probably the part of the banks history that few would have realised is that it was actually privately owned for much of its life.

The bank was launched as a joint-stock bank in 1694, and remained private until 1946, when it was nationalised as a result of another War and a drain on the country’s reserves.

The Nationalisation Act also gave the Government the power to issue "directions" to the Bank which the Bank claims have, thus far, not been used.

Some might beg to differ.

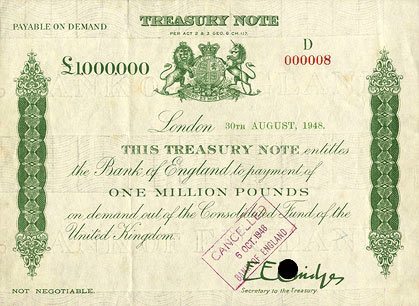

Meantime, if you weren't aware, there are £1 million and even £100 million notes being used by the Bank.

They are purely for internal transfers, but wouldn't you like to get your hands on one of those?

This is the sixth in a series about how the City of London developed its financial prowess and system.

Previous entries include:

- Part One: The Romans

- Part Two: The Vikings

- Part Three: Medieval Times

- Part Four: The Tudors

- Part Five: The Stuarts

- Part Six: The Bank of England

- Part Seven: Lloyd's of London

- Part Eight: The London Stock Exchange

- Part Nine: The 1700s

- Part Ten: The Victorians

- Part Eleven: World Wars

- Part Twelve: After World War II

- Part Thirteen: The Big Bang

- Part Fourteen: Crisis

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...