I was going to blog about something ephemeral, academic,

insightful and rich today … but then realised that I’m feeling energised by a relaxing

weekend in Stratford, the home of Shakespeare, and felt it worth blogging about

a few things that were intriguing there.

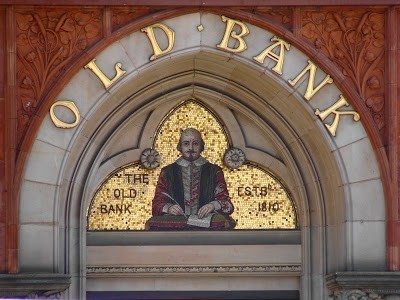

One of the most intriguing things in Stratford is HSBC’s

bank branch.

The bank owns one of Stratford's few Victorian Gothic

buildings, and stands at a key junction where examples of 16th

century, 18th century, 19th century and 20th

century buildings combine to create a small microcosm of history.

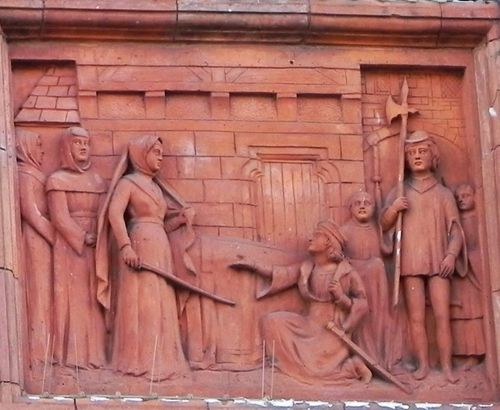

The building itself is made from red brick and decorated

with red terracotta tiles.

Several of

these tiles are actually friezes and sculptures that illustrate Shakespeare’s

works.

For example, above the main door of the branch which was

built in 1883, is a reference to the Old Bank (the original building it replaced)

with a Shakespeare mosaic.

Above that is a scene from the Merchant of Venice in terracotta.

The scene portrays Act 3 Scene 2 of the play, where Nerissa

and Portia watch Bassanio make his choice of the caskets, and are watched by

Gratiano and a boy.

There are in fact 15 terracotta sculptures on the facia of

the bank.

Each frieze portrays a different play and was produced by

Samuel Barfield, a stonemason who lived in Leicester. Barfield’s work was well-known in the Midlands

and his stone sculptures can still be seen on the clock tower and the Old

Midland Bank in Leicester (built in 1872), the Paxton Memorial in Coventry and

on the Chamberlain Fountain commemorating the mayoralty of one of Birmingham’s

most influential figures, Joseph Chamberlain.

Thousands of tourists pass the HSBC branch today and most

will probably spot the Old Bank portrait above the door although I suspect most

do not notice the terracotta frieze. Its position high above the heads of

passers-by may have given it protection over the years, but also makes it

difficult to see.

So here is a guide to the fifteen panels, courtesy of the

Shakespeare blog.

The panels are in three groups of four, tragedies, comedies

and histories, with three single panels on the corner between comedies and

histories.

First there is King

Lear, Act 2, Scene 2, where Cornwall, Goneril and Regan encourage Lear and

the Fool to go out into the storm.

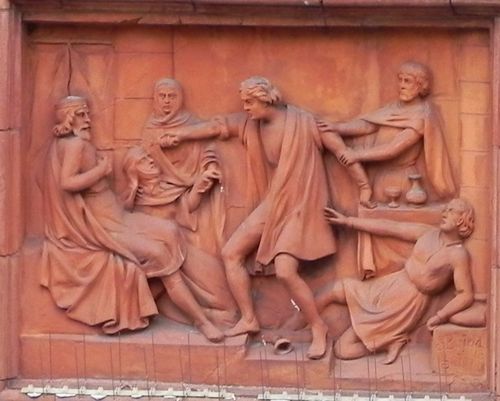

Next is Hamlet,

Act 5, Scene 2, where Claudius recoils as Gertrude, assisted by a lady,

collapses. Horatio holds Hamlet back and Laertes, wounded, calls “The King, the

King’s to blame”.

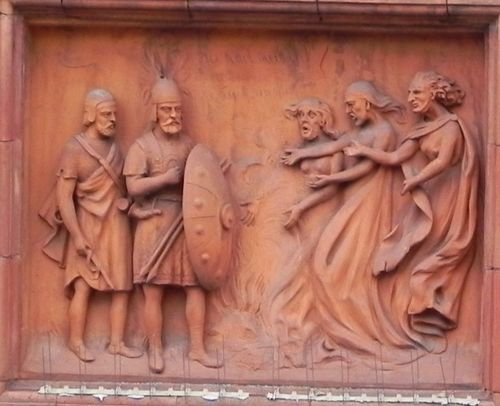

Third is Macbeth,

Act 1, Scene 3, as the three witches appear to Banquo and Macbeth saying:

“All Hail, Macbeth”.

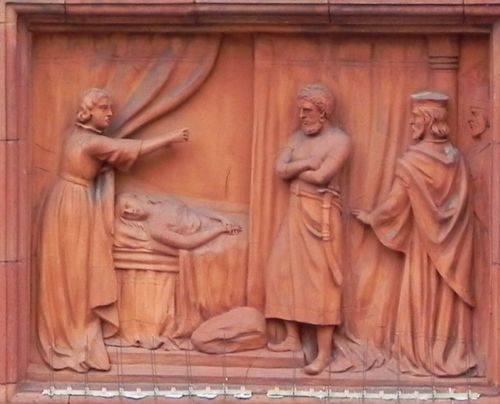

Othello, Act 5

Scene 2, follows as Emilia pulls back the curtain to reveal Desdomona’s

murdered body. Othello stands by, watched by Montano.

Next, As You Like It,

Act 3, Scene 5 with Phoebe, Silvius, Rosalind, Celia and Corin.

The Two Gentlemen of

Verona, Act 5, Scene 4, is shown with Valentine challenging Proteus who is

attacking Silvia, while Julia stands by, watching. “Ruffian, let go that rude

uncivil touch”.

A Midsummer Night’s

Dream, Act 3, Scene 1, portrays Quince calling out as Bottom appears to the

mechanicals wearing the ass’s head. “O monstrous! O strange! we are haunted”.

Puck watches from above.

Twelfth Night, Act

3, Scene 4, provides us with Sir Toby egging on Sir Andrew to fight with Viola,

backed up by Fabian.

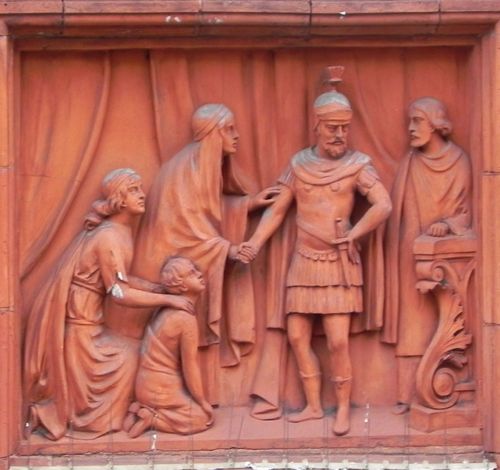

Coriolanus, Act 5,

Scene 3, shows Virgilia standing with Young Martius who kneels, while Volumnia

pleads with her son Coriolanus.

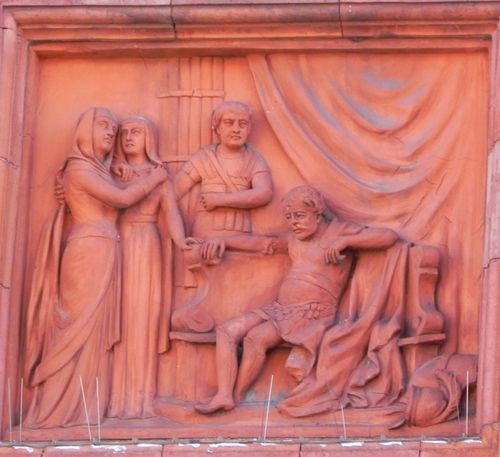

Then we have the scene from the Merchant of Venice as shown above, followed by Antony and Cleopatra, Act 3, Scene 11.

Cleopatra, supported by Charmian approaches Antony who is in despair after

losing the battle. Eros addresses him “Most noble sir, arise, the queen approaches”.

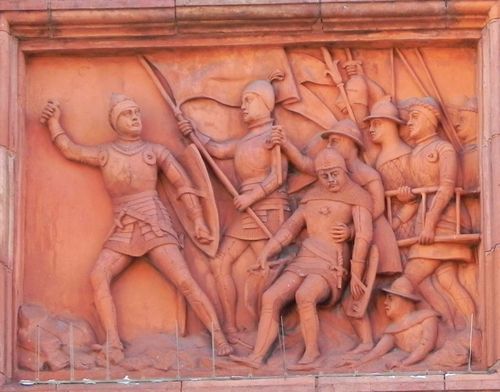

Then we get the histories with Henry V, Act 3 Scene 1, as Henry cries “Once more unto the breach”

and leads his troops at the siege of Harfleur.

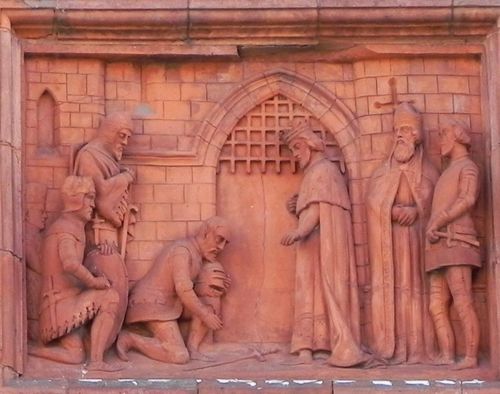

Richard II, Act 3

Scene 3 (currently playing at the RSC with David Tenant as the King) is shown

where, outside Flint Castle, Bolingbroke kneels to Richard and states: “fair

cousin, you debase your princely knee”. Bolingbroke’s supporters are

Northumberland, Percy and York, while behind Richard are the Bishop of Carlisle

and Aumerle.

King John, Act 4,

Scene 3, forms the penultimate frieze as the Bastard intervenes between

Salisbury, who has drawn his sword, and Hubert over the body of Prince Arthur.

Pembroke and Bigot stand by watching.

Finally, we reach Richard

III, Act 1, Scene 2, as Richard offers his breast to Lady Anne for her to

kill him. “Nay, now dispatch: ’twas I that stabbed young Edward”.

Such sophistication of bank branches can be seen in many

historical buildings but this one is a standout and must be the most amazingly historical

bank branch I have ever seen (unless anyone wants to suggest a better one?).

Meanwhile, HSBC celebrated Shakespeare’s birthday this year, with these anecdotes about the Bard.

The word “money” appears more than 150 times in

Shakespeare’s complete works, and rarely in complimentary terms. Iago in

Othello says cash is worthless compared to a good reputation (“who steals my

purse steals trash”); Polonius in Hamlet warns of the dangers of finance in

human relationships (“neither a borrower nor a lender be”); and the ruthless

banker Shylock in The Merchant of Venice presents a troubled figure.

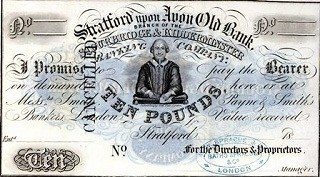

This has not stopped printers putting Shakespeare’s likeness

on money. A £10 note dating from around 1870 was issued by the branch of the

Stourbridge & Kidderminster Banking Company, which would later become part

of Midland Bank and then HSBC.

The issuing branch is the one with the friezes and

sculptures.

You may wonder why a branch could issue a note but, back

then, most regional banks outside London printed their own notes. It was

traditional to include pictures of local landmarks or local heroes, and it is

natural that a bank in Stratford-upon-Avon chose Shakespeare.

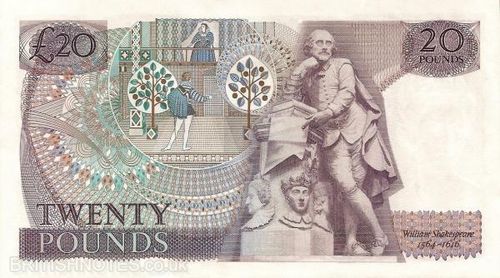

Privately issued notes became rarer as the Bank of England

gradually consolidated its position as the main body for minting currency, and

by the 1920s they had almost disappeared. However, in the 1970s, the Bank of

England started putting pictures of notable historical figures on the back of

its notes – and the first person chosen was Shakespeare. He was on the back of

the £20 note that was in circulation in the 1970s and 1980s.

What culture and so, to conclude, all I can say is that:

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts ...

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...