In most science fiction movies, there is no money. The Hollywood visions of the future have wiped out the need for cash, and I’ve blogged before about Gene Roddenberry’s views on money in Star Trek: “Money is a terrible thing”.

His idea is that money will disappear as we approach space and, as we send rockets out to Pluto, his vision is getting nearer. Money doesn’t disappear from society in our current state vision however. It just disappears in physical form and moves to a digital structure. The new digital structure of money is not just a cryptocurrency however.

The cryptocurrencies may be the value exchange mechanisms between machines, but it’s the chips inside machines that are our new wallets. As we move into Web 3.0, we move into machine-to-machine commerce and machine-to-machine commerce can only be transacted in a neatly organised value system.

My vision for this new value system is that every machine, or commercially enabled thing if you prefer, will have intelligence inside. A chip. That chip inside will be designated an owner. The owner in most cases will be you and me, and these things we own are part of our recognised digital identity structure.

So I have a number of things designated as mine on a shared internet ledger. My car, fridge, television, front door, heating system, several watches, shoes and jackets are all registered as mine. All of these things have chips inside, and these chips give them intelligence. My heating can be controlled from my watch; my television orders my entertainment; my fridge orders a regular grocery shop; and my car drives itself to gas stations and refuels as often as needed.

In order to do this, all of these devices have been recorded as mine. They are attached to me through my digital identity and my digital identity is recorded on a trusted shared ledger for the internet of things. If my car refuels too often or my fridge makes an exceptional order for over $1000 of groceries, I get alerts that require my biometric approval.

All of these things are transacted through the air, via a shared ledger of trusted exchange. In my case, they are recorded on some form of poundchain; Americans operate on a dollarchain; and the Chinese on a renminbichain.

These digital currency chains not only transact value exchange but also manage identities and ownership. This is how you can achieve the science fiction vision of value exchange immediately and invisibly through the air.

The reason why this is a likely outcome of our developments of the internet of value and Web 3.0, the internet of things, is that we are moving forward to a revolution in trade and, with every revolution in trade, we have a revolution of financial value exchange.

This can be seen from the earliest forms of homo sapiens and how we adapted through every generation of trade. Originally, there wasn’t a great deal of trade between tribes. Tribes kept pretty much to themselves.

In his brilliant book Sapiens, Professor Yuval Noah Harari provides a brief history of humankind. He explains how we have created a world of fiction in order to allow humankind to ascend to the top of the food chain.

Companies, money, governments, religions, law and all the things that structure our world are all fictional creations of humankind that allowed us to conquer the world. It’s a complicated idea to explain here, but the gist is that no animals have companies, money, governments or legal systems. Most are controlled by a hierarchy through an alpha male or queen matriarch, but they do not have these items that structure trade in the way we have created them. We created these things to allow hundreds of people to live and work happily together. Most animals have tribes of no more than a couple of dozen creatures. We have tribes of hundreds of thousands, organised in cities and all working alongside each other thanks to our formalised structures of trade.

In the book, Harari traces (Homo) Sapiens back over 200,000 years and notes that 70,000 years ago we began to migrate from Africa across Asia and then, 45,000 years ago, to Australia and more recently (16,000 years ago) to the Americas. The key to our expansionism was language and shared fictions that enabled us to believe in gods, demons and priests, and allowed us to move from being nomads to fishermen to farmers, exchanging trade and value along the way.

“While we can’t get inside a Neanderthal mind to understand how they thought, we have indirect evidence of the limits to their cognition compared with their Sapiens rivals. Archaeologists excavating 30,000 year old Sapiens sites in the European heartland occasionally find there seashells from the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts. In all likelihood, these shells got to the continental interior through long-distance trade between different Sapiens bands. Neanderthal sites lack any evidence of such trade. Each group manufactured its own tools form local materials …

“The fact is that no animal other than Sapiens engages in trade, and all the Sapiens trade networks about which we have detailed evidence were based on fictions. Trade cannot exist without trust, and it is very difficult to trust strangers. The global trade network of today is based on our trust in such fiction entities as the dollar, the Federal Reserve Bank and the totemic trademarks of corporations. When two strangers in a tribal society want to trade, they will often establish trust by appealing to a common god, mythical ancestor or totem animal. If archaic Sapiens believing in such fictions traded shells, it stands to reason that they could also have traded information, thus cr4eating a much denser and wider knowledge network than the one that served Neanderthals and other archaic humans.”

Harari’s book is fascinating, and this extract is partly an explanation as to why homo sapiens are the only hominid’s left on this planet. 200,000 years ago, there were many other hominid species including Homo Erectus, Homo Neanderthalensis, Homo Rhodesiensis, Homo Tsaichangensis, Homo Sapiens and Homo Floresiensis. According to analysis by Harari and others, it is the very fact that we could create trade systems based upon shared fictions that exchanged forms of value through language, information and things that were useful or beautiful – shells, obsidian, stones, flint – that we ascended to become the most intelligent of species and, consequently, dominated the planet.

The thing is that as we became sentient or, as Harari refers to it, underwent a Cognitive Revolution, we began to search, explore and then, some years later, farm and settle. Until just over 10,000 years ago, most humans were hunter-gatherers. We were nomads. We would move from area to area through the seasons, exploring and gathering food. Sometimes we would starve, but we had no means of developing crops. That changed after the last Ice Age, which some scientists believe created annual plant growth. As a result, we could seed fields of grain and grow food stocks.

As farmers, we could stop roaming and settle. This is why we find the first cities appearing 9,000 years ago, although it is debatable as to which was actually the first city.

Farming worked well to allow humans to produce food to last throughout the year, and hence we could start to assemble and settle together. Then we had too much food and produce, and the systems broke down. As a result, we had to create another form of value exchange and, being homo sapiens, we invented this new shared fiction of money.

Now I blogged about the rest of the story of how we created money the other day but, just in case you didn’t see it, here’s the history of money as it completes the story started here.

Various stories appear about money but the first mentions appear to date back over 12,000 years ago, when ancient tribesmen in Antonia swapped Obsidian stones to store value. What this represented is a move from basic production of goods to the trading of goods and services, and we have seen the progression of the use of currency and value stores through the ages as we developed civilisations and societies. However, our progression of these stores of value are changing and moving faster and faster, as our technologies develop faster and faster.

For example, the Antonians not only traded in stones but other forms of value, from cattle to sheep. In other words, it was more of a form of bartering than currency itself. 7,000 years of development led to a revolution in trade and commerce however. In fact, every time we progress in technology, trade and commerce, we have a revolution in finance.

The revolution of 3,000 B.C. was in Ancient Sumeria when the priests invented money. This first form of money was a coin, a shekel, which priests offered to farmers in exchange for their overabundance of produce. This was created because the Ancient Sumerians were one of the first civilisations to farm, and create an orderly system of food production. In other words, we moved from an informal trading system using tokens, to a system that was a very different formal structure of trade. In other words, we went through a revolution of trade and commerce as farming became commonplace in civilised communities.

Farming created money – coins that were made from precious metals, such as gold. This worked for an eon but proved difficult when distances were involved. Carrying a heavy bag of gold coinage was not the best when you might encounter bandits or thieves, or had a horse that could only carry so much weight. Hence, the Chinese invented paper money 2,300 years later in 740 BC. This was predictable in value – unlike gold coinage that had to be weighted and measured and, in some cases, mixed with materials that were not pure. The paper money was issued and backed by government - the Tang Dynasty - and proved to be a far more reliable mechanism for trade.

So we moved from barter before farming to coins for a trusted value store to cash for trade across distances.

These worked well until the next big change in trade and commerce: the Industrial Revolution. As businesses were created that sourced goods from overseas and traded across country boundaries, a new form of currency was needed. In particular, the Industrial Revolution saw people trading across great distances and across borders. Hence, traditional coinage was too heavy to carry across such great distances, bearing in mind that they were made from gold, and governments started to licence institutions, banks, to enable trade on their behalf across borders. The new government licenced institutions could therefore issue paper money – a cheque or bank note – that could be as trusted as a gold coin. This was a key move – from coins to paper – and enabled the rapid expansion of trade and commerce globally, as the industrialisation of economies developed fast in the eighteenth century.

However, it didn’t work quite so well when workers moved from factories to offices. During the 1950s, after the Second World War, Americans led the revolution in office work and professional entertainment became en vogue. The trouble is, when you’re entertaining a client, it proves to be a real pain if you end the lunch or dinner and have to write a cheque. Writing a cheque interferes with the client engagement – you have to take your eyes off the focus of conversation – and so Frank McNamara invented the credit card.

Frank was an executive at the Hamilton Credit Corporation and had a problem. His finance company was struggling with uncollected debt, whilst Frank needed a way to make more money. McNamara came up with taking the idea of a charge card, back then being used mainly just in department stores, to the restaurant business. His innovation was to use the charge card in restaurants and then add an interest to the monthly payments. That way the finance company was able to make a profit from every card that was given out.

He managed to convince many restaurants in lower Manhattan to sign up for the card, by offering customers a 10% discount for every purchase. This meant that many restaurants and stores signed up, because there was no fee or charge and it made it easier to purchase meals without worrying about cash. This led to the launch of The Diner’s Club in 1950, and so was born the new industry of the credit card.

This brings us nearly up-to-date as we have seen, through these 12,000 years of history, that we moved from:

- barter for nomadic societies; to

- cash for farming societies; to

- cheques for industrial societies; to

- cards for office societies.

But now we live in a networked society. A globally connected world. That demands a new form of currency and some would immediately point to bitcoin or the blockchain, as I mention this. That’s relevant, but it’s only part of the answer. Just as cards needed Visa and MasterCard to succeed globally; and just as cheques and cash need to be backed by a trusted mechanism of government licencing or precious stones; we need an internet age value exchange mechanism that is trusted, immediate and works through time and space, to support the chip-based economy.

In the chip-based economy, anything can exchange value with anything, anywhere, anytime. All objects will soon have intelligence inside, a chip inside, and will need a method of transmitting value and exchanging and trading. This internet-age system will therefore be based upon chips.

The chip-based economy means that the internet of things can work. I descried this in another recent blog post, which I’ll repeat here to save you clicking.

You buy a fridge, a car, a house, a smartphone, a wearable, a whatever. All the things you buy have clear serial number identifications as well as chips inside to enable them to transact wirelessly over the web. Upon purchase, your device is recorded as being yours using your digital identity token (probably a biometric or something similar). That recording of that transaction takes place on the blockchain.

Now, you have multiple devices transacting upon your behalf. Your fridge is ordering groceries from the supermarket; your car auto refuels as it self-drives the highways; your house reorders all the things needed for the robot vacuum and other cleansing devices it uses; and so on.

Each transaction is a micro-purchase around your wallet, but involving no authentication of you. The authentication is of your devices. Should a large transaction occur, or maybe just to check-in as contactless payments do with every twenty or more transactions, you are request to agree that this is your device ordering on your behalf by providing a TouchID or similar.

And all of this is being transacted and recorded on the open blockchain ledger of your bank cheaply, easily and in real-time.

What this provides is the scenario I keep talking about. The scenario invented years ago by Gene Rodenberry, when he came up with the idea for Star Trek. Now Star Trek has lots of things that were forecasts of the future that came true from communicators that were the predecessors of Motorola flip phones to body scanners that could be hand held. One of the other predictions was that we wouldn’t need money.

Did you ever see anyone ever pay for anything on Star Trek?

The reason you don’t need money in the future is that all the transactions you make take place wirelessly around you, through your internet of things. You walk into a store or mall, and all of your devices and identity are communicating your location and intention. As a result, you never pay for anything. You just authorise with the blink of an eye or the wave of a watch.

In other words, we have moved from:

- barter for nomadic societies; to

- cash for farming societies; to

- cheques for industrial societies; to

- cards for office societies; to

- chips for networked societies.

The chip-based economy, enabled by the blockchain, that can be exchange finance, goods and services for anyone trading anything, anywhere, anytime. This is the basis of why we invented money and it is why I call the blockchain the Uber of Finance, as it’s creating a globally connected marketplace for trusted exchange.

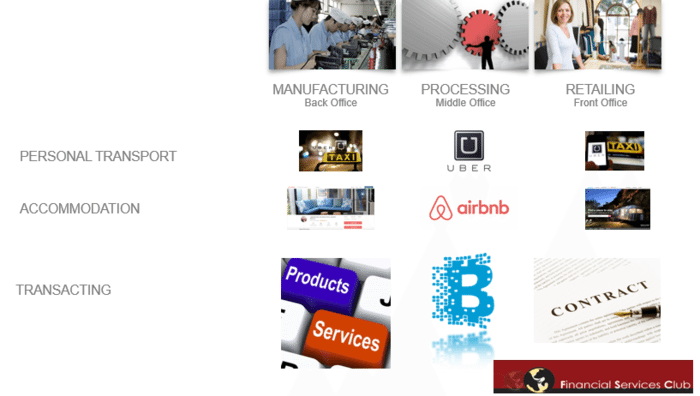

Uber is a marketplace connecting buyers (people who want a ride) with sellers (drivers). The same with Airbnb connecting buyers (people who need to sleep) with sellers (bedrooms). The blockchain is doing the same by connecting people who need to transact (buyers) with those who have what they want (sellers) through a trusted third party (the blockchain) that is decentralised and networked.

As Michael Mainelli explained at our Financial Services Club meeting about the blockchain last week: “money is a technology communities use to trade debts across space and time.”

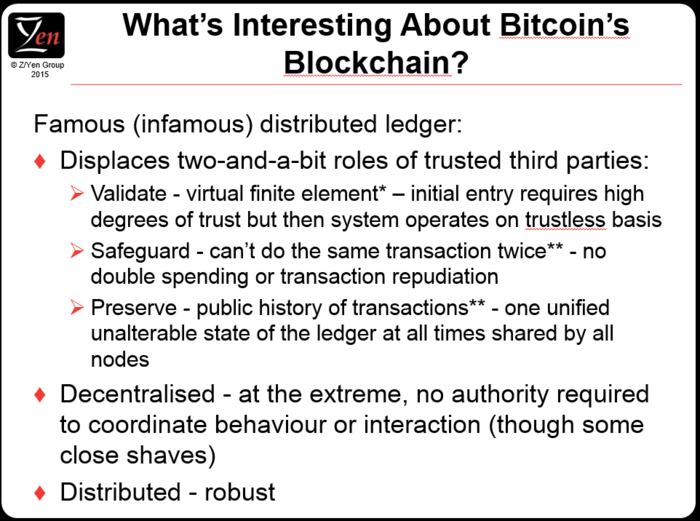

In saying this, Michael went on to discuss how we could use the blockchain to create a shared ledger for shared economies. He pointed out that the reason we have a financial system is because most value exchange is based on a lack of trust, and so you need a central authority to provide this trust. The central authority provides three key things that enable the value exchange of cash, cheques or cards to occur:

- they validate the value token is real and not a forgery;

- they safeguard that, once you have accepted the token in exchange for goods and services, it is irrevocable; and

- they preserve the details of what was traded, so that there is no omission or lie in the transaction.

I thought it was interesting therefore, when Michael posted this slide:

That he, along with others, are all believing we are developing into the true system for the chip-based economy based upon some form of blockchain development. It is for these reasons that I say the blockchain is the Uber of finance, as it’s creating the marketplace for globalised value exchange that is trusted, secure and irrevocable.

Smart.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...