Web 1.0 – the network begins

As mentioned yesterday, almost half a century of developments in technology led to the launch of the web as we know it today, following Tim Berners-Lee’s paper detailing HTML and URLs. This was in 1990 and, consequently, the internet morphs almost every decade. This makes our decade – the 2010s – the era of Web 3.0 and the building of the ValueWeb. But let’s go back to the 1990s and what happened.

The first website was launched by Tim Berners-Lee on August 6, 1991, and was pretty basic, as were most of the early websites.

Most were launched by academic and research firms, and were there to collate information. Wired, Bloomberg and IMDB launched websites in 1993, and more followed. But these websites were mainly providing information. Some were more visual – a marketing magazine online – but none were interactive.

Interactivity didn’t really start until the pornographers saw the potential of the internet. As with any new technology, sex and pornography is the catalyst that drives early adoption. For example, Event Horizons BBS was grossing more than $3.2 million dollars a year by 1993. Jim Maxey, who ran Event Horizons, employed ten people simply to scan photographs, format them, and put them online for download. They didn’t do any marketing as such, as news got around through word of mouse, and a whole raft of sites launched leading to commerce online. Unfortunately, it also led to a proliferation of child pornography, previously inaccessible easily. The NCMEC estimated in 2003 that 20%of all pornography traded online was child pornography, an increase of 1500% in six years.

In other words, the drive of pornography led to online commerce, with the first payments being taken through credit card forms online. The first commercial website launched was books.com. Books.com was owned by Book Stacks Ltd, a US bookstore that had been running a bulletin board in the 1980s and moved online in 1992, three years before Amazon launched, taking credit card payments. Books.com was eventually acquired by Barnes & Noble.

By 2014, online retail commerce is worth £100 billion a year in the UK alone but twenty years before, on August 11 1994, the first secure, commercial online payment was made by American retailer NetMarket.

As mentioned Amazon launched in 1995, as did eBay, and other modern standards like Google (1998), PayPal (1999 as x.com) and Alibaba (1999) followed. In other words, the era of internet commerce began just twenty years ago.

This was the decade of Web 1.0: the evolution of the first website into 1000s of sites delivering everything from infomercials to easy commerce. It was the time of Netscape and AOL, of dial-up lines and modems.

The key features of this first-generation internet is that it was highly controlled and structured. Businesses ran the internet. Websites were offered by business to consumers, and everything was about B2C and B2B. Following information services, commerce enabled the web to really take off. The first payment services were just credit card forms, as mentioned, but soon companies realised that form filling was onerous and a barrier to commerce and so firms dedicated to payments launched.

PayPal is the American firm we all recognise today as the leader in online payments in Europe and America (in Russia it’s Yandex and China AliPay), but this wasn’t always the case. Before eBay acquired PayPal in 2002, they had their own system called Billpoint, developed in partnership with Wells Fargo.

Billpoint processed around 25% of all online payments whilst PayPal processed 65%. Equally, PayPal was not always PayPal. Before 2000 it was x.com, created by Elon Musk, and Confinity, created by Peter Thiel and friends. Interestingly, in this 2001 article on Bloomberg, they write about PayPal’s potential IPO:

In an Internet market starved for success stories, PayPal (PAPXX ) is one of the few upstarts brimming with potential. Still, the Palo Alto (Calif.) company, which handles payments for buyers and sellers on the sites of auctioneer eBay Inc. (EBAY ) and other e-commerce players, left the high-tech world agape when it filed paperwork on Sept. 28 for an $80 million initial public offering … earlier this year, PayPal executives discussed selling to eBay, Citibank (C ), and other companies, but no one would approach PayPal's asking price of more than $700 million, according to analysts and investment bankers.

Interesting how times change. PayPal valued at $700 million in 2001 now has a market capitalisation of near $50 billion. It just goes to show how important the payments system is to online commerce.

Meanwhile, in a final thought on Web 1.0, banks launched their online services and, eventually, offered online banking. Most bank websites were initially just brochures, and the first online banking systems began around 1995 with Wells Fargo. I remember these times quite well, as most banks believed they could shut branches and shift all their customers to online banking, but it wasn’t that easy. Customers didn’t trust banking online and, in many instances, the online banking services were pretty awful too. The sites were just a transition from the branch-based ledger of debits and credits to an online ledger of debits and credits, and it hasn’t changed much since.

1990s bank websites

2010s bank websites

Intriguingly, the real change only occurred when banks guaranteed that online banking was secure. So, in the spirit of finishing Web 1.0 analysis with a flourish, I’m going to share with you one of my favourite TowerGroup research notes, produced by George Tubin in 2004. This research note applies to all online banking services, and explains why Bank of America has been so committed to not just rolling out online banking, but also mobile and digital banking services. Enjoy …

How Bank of America became the biggest US online bank

Coming out of the dot-com boom, brick-and-mortar businesses across all industries were forced to reexamine their online strategies. After the mad dash to gain market share and "online real estate," the real economic underlying value of the online channel came under considerable scrutiny. This question was especially difficult for the banking industry with its highly complex delivery system, organizational structure, product mix, and geographical reach. In short, measuring the economic value of the online banking channel is difficult.

Unlike most other top-tier US banks, Bank of America was determined to confront this issue head on. Realizing that measuring the profitability or return on investment of the online banking channel directly was fraught with problems, the bank decided to approach this issue from a customer-centric perspective. Rather than trying to determine the value of the online channel in isolation, the bank chose to determine the value of customers that used the online channel compared to those that did not.

Online Banking Time Series Analysis

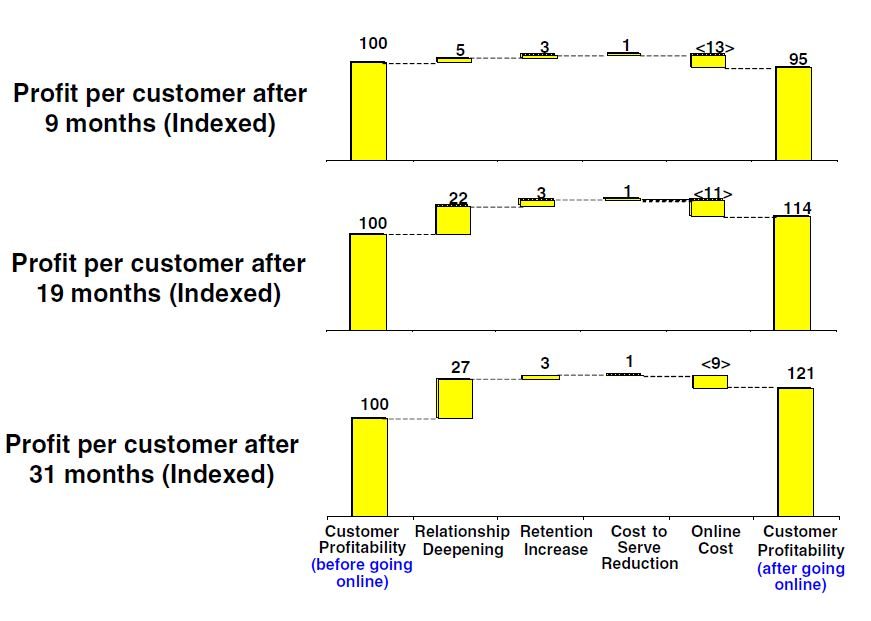

Although the approach and results of Bank of America’s online customer profitability study have been publicly available for some time, a brief description is warranted for those who may not have had the opportunity to review it. After evaluating approaches to determine the nagging question of profitability of the online channel, Bank of America took a unique approach to determine the answer. Rather than simply comparing the profitability of online customers as a segment to that of offline customers, the bank performed a time series analysis that tracked both online and offline customers over a period of time.

Online customers were compared to control groups of customers who were not online, based on several measurements taken over an extended period. To isolate the effects of the online channel on the overall customer relationship, control groups were chosen that had demographic and tenure attributes similar to those of the online group. This analysis was structured to isolate the effects of online banking on customer profitability.

Bank of America started collecting this data in late 1998 and completed the first time series analysis in the middle of 2000. The study showed that, after going online, customers actually became more profitable than their control group counterparts. Put another way, the study determined that online banking led to higher customer profitability.

Although online bill pay customers cost more to serve, these costs were more than offset by an increase in account retention rates and an expansion in the number of products used. But the most significant profit driver for online customers proved to be an increase in account balances. That is, the interest income derived from higher account balances produced the most significant lift in customer profitability. After nine months, profitability of the online groups was 5% lower than the profitability of control groups, but by the end of the 31-month period, online customers became 21% more profitable than their offline counterparts.

Results of Bank of America Online Bill Pay Customer Time Series Analysis (2001)

To gain the backing of the entire organization, Bank of America’s e-commerce unit realized that it should share the online profitability findings widely. Not only did the bank communicate its findings across the entire organization, but Ken Lewis, Bank of America’s CEO, actually presented the bank’s findings outside the company. In fact, the presentation is publicly available on the company’s Web site.

The results of the time series analysis formed the crux of how the bank makes decisions about online banking, including the decision to offer free online banking and bill pay. As a result of this and subsequent studies, Bank of America decided to aggressively pursue projects that would increase online banking adoption and usage across its customer base. Subsequent time series studies with different customer groups have shown similar results.

As the technology infrastructure was being improved to support the bank’s anticipated growth, the organization focused on overcoming customers’ potential misperceptions or objections to online banking.

Deeply committed to Quality and Six Sigma approaches, the bank’s management believed that by really listening to customers and understanding their needs, the bank could focus on implementing programs to improve customer satisfaction and delight its customers. The organization believed that this approach would lead to broader relationships and, hence, higher customer profitability.

The bank used a Six Sigma approach known as "Voice of the Customer" to understand what customers really wanted in an online banking application and to prioritize projects aimed at removing barriers to customer adoption and usage. This approach allowed the bank to target its marketing and development efforts to areas that would produce tangible results. Further, the bank shared findings from the Voice of the Customer project across the organization to provide a common understanding among the thousands of bank associates.

After carefully planning, a Voice of the Customer project involves gathering both solicited and unsolicited input from the customer base. Solicited input came from several sources, including focus groups, online questionnaires, and mail surveys. Unsolicited input came from e-mail, mail, contact centers, and branches.

To obtain a comprehensive view of the customer base, the bank ensured that input came from both online and offline sources. Reams of data were then organized and scrubbed to provide a good basis for Voice of the Customer analysis. As with any data analysis project, the first step was to ensure the validity and accuracy of the data to be analyzed.

Voice of the Customer analysis proved fruitful

The bank was able to translate and prioritize customers’ objections to online banking into several categories but discovered that four objections were the most significant barriers to adoption. By concentrating on these top objections or barriers, the bank was able to implement programs and policies that directly addressed the areas that would eventually provide the most benefit to their clients, and henceforth, the bank. Although the bank continues to conduct conducts Voice of the Customer projects and share the analysis across the organization, on its road to 11.2 million customers, the bank needed to overcome these four primary barriers to online banking:

Barrier 1: "Online Banking Costs Too Much"

Today, it is fairly common practice for large retail banks to offer online banking for free. However, this was not the case just a few short years ago. Most banks would charge a monthly fee for online banking or online bill payment, or provide it for free with high minimum balance requirements. In May 2002, Bank of America announced it would join the budding movement to provide online banking with bill pay free of charge. This decision removed one of the largest obstacles that kept customers away from banking online: cost.

Thanks to the bank’s sheer size and market impact, almost the entire industry followed suit and began offering free online banking with bill pay. However, many of the other banks did not fully grasp the impact of this move. They had not performed any kind of detailed customer profitability analysis and did not know the value of their respective online banking programs. Most banks feared that online banking was unprofitable for them to begin with and that giving it away would only make it more unprofitable.

But, because the largest retail bank in the US was giving the service away, other banks felt forced to provide the service for free as well. They hoped that Bank of America knew what it was doing and that providing free online banking would somehow provide a benefit.

Indeed, Bank of America knew exactly what it was doing when it made the decision to go free. Its time series analysis proved that customers became more profitable as a result of going online. The elimination of online banking and online bill pay fee income was far outweighed by the increased profitability derived from customers banking online.

Barrier 2: "Online Banking Is Not Safe"

Online security continues to be a top concern for many consumers, especially in light of the many phishing and spoofing scams that have surfaced across the financial services industry. Even before the recent spate of phishing attacks, consumers were wary of conducting financial transactions online. Consumers continue to believe that simply signing up for online banking could enable a fraudster to gain access to one’s username and password and thereby gain access to the account, either by intercepting information during an online banking session or by simply "hacking" the username and password. Consumers believe that without an online account set-up, they are not vulnerable to this type of fraud. They are unaware that thieves can use stolen identification information to establish an online banking account.

In order to make customers more comfortable with banking online, the bank realized it had to stand behind its product. Bank of America was one of the first institutions to offer its customers an online banking guarantee, providing "$0 Liability" for any unauthorized activity originating from online banking.

Customers, of course, are required to protect their usernames and passwords, not leave their computer unattended during an online banking session, and promptly notify the bank of any unauthorized activity.

Barrier 3: "Online Banking Is Difficult"

Bank of America realized that many consumers stay away from online banking because they fear making mistakes in performing financial transactions. Ordering the wrong book is one thing; accidentally sending your mortgage payment to a shell company in Dubai is another. The bank continues to focus considerable effort on simplifying their customers’ online experience from enrollment to transaction execution to cross-sales.

In a recent review of top online banking providers, TowerGroup found Bank of America to be clearly in the top tier (along with Citibank and Wells Fargo). The top providers not only provide a higher level of features and functions than their peers but also seem to have a knack for providing highly usable and intuitive user interfaces.

Barrier 4: "There’s No Real Need to Bank Online"

Other than simple ATM withdrawals, consumers traditionally looked to branch and contact center agents to execute their financial transactions. The checkbook remains a sacred relic and check writing a venerated practice among US consumers. Suggesting that bank clients stop using their dear and trusted friends at the local branch and deprecating the check register are considered heresies in many circles.

Yet, online banking promises to replace or supplement traditional banking methods with simple, real-time, 24-hour banking.

According to TowerGroup primary market research, approximately 93% of all consumer banking customers continue to visit a bank branch at least once a month. Bank of America realized that the most effective way to convince its client base to try online banking was to do so in their branches. But, to promote online banking in the branches would require the branch staff to fully understand and support this effort. If consumers sensed that the branch staff was not enthusiastic about online banking, or worse, unwilling to use online banking themselves, the response would be clear: "If bank employees don’t use it, why should I?"

To encourage the branch associates to use online banking, the bank ran several enticing promotions with prizes, including a PT Cruiser and $10,000. Not surprisingly, in a short time over 80% of all branch associates were using online banking on a regular basis. Because of the genuine enthusiasm for online banking exhibited by the branch staff, in-store enrollment for both existing and new customers showed a marked improvement. Today, the bank generates a greater proportion of new online banking enrollments via the banking centers than via the Web, with the majority of customers being new to the bank.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...