I've written a lot about Ant Financial - they're a 30,000 word case study in my new book - mainly because they are the first payments platform to focus upon global reach for financial inclusion. That is not to say that I am ignoring the other platforms: PayPal, Stripe, PayTM and such like. In fact, one other big platform of note is WeChat Pay from Tencent.

So I was delighted to see that Steven Millward wrote a great piece on Tech in Asia about WeChat the other day. The fact is that WeChat and WeChat Pay in China is a monster but, to go global, they will have more challenges as Ant Financial has got the key partners first. In other words, imho, Ant has first mover advantage. Mind you, that has not stopped WeChat from competing effectively before, as evidenced in this timeline article from Steven.

7 years of WeChat

WeChat was born seven years ago. Here’s a potted history of China’s most essential app.

October 2010: In development

In a Tencent office in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou, away from the company’s Shenzhen HQ, a small team started working on a mobile chat app.

January 21, 2011: Tencent debuts messaging app

It began quietly on this day seven years ago when Tencent – already China’s social media giant with its MSN-style QQ instant messenger and accompanying Qzone social network (with 780 million active users at the start of 2011) – made a mobile-only messaging app. It was a big break from Tencent’s very PC-era social networks and online gaming empire.

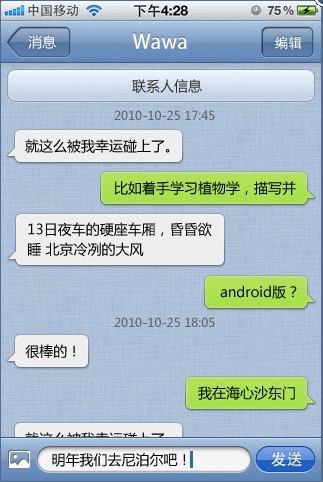

Here’s how it looked at launch, initially only on iOS:

Image credit: The Next Web

The new app was called Weixin in Chinese. There was no English name yet. The Next Web, the only major international news outlet to report the launch, transliterated the Chinese name and dubbed it “micro letters.”

China’s three telecoms companies already had online messaging apps that were proving popular, but Tencent wanted to bring down the telco barriers that existed between people. Screw the telcos: its chat app would disrupted SMS and work on any phone and mobile service.

The launch of Weixin came as Kik and WhatsApp – both released in 2010 – were gaining traction.

WeChat’s first iteration had basic features: text messaging, creating voice clips, and, sending photos.

August 2011: Adds video clips

Anyone familiar with the dizzying array of features in Tencent’s other products would have guessed that WeChat would not stay on minimalist mode for long.

Seven months after launching, WeChat added video clips and a “find nearby users” function.

With Chinese people slowly shifting from 2G to 3G, WeChat ensured that videos would be shrunk down to reduce the cost of sending them when not on wifi. A one-minute video could be condensed so that it was just 1 MB in size.

March 2012: Hits 100 million registered users

About 14 months after launching, WeChat hit a major milestone when Tencent reported it had 100 million registered users. This was before the company started revealing the number of monthly active users.

April 2012: Weixin becomes WeChat

After a year of Tech in Asia calling the app Weixin, Tencent picked an English name for it.

The move seemed to signal that the Chinese tech titan wanted to go global with its newest social network, something that the company had never done before.

Later that month, WeChat’s v4.0 update added in the Thai, Vietnamese, Indonesian, and Portuguese languages. It already had English.

June 2012: Chatting up India

Tencent pushed WeChat into India with a high-profile, celebrity-filled launch – including lots of pricey ads on Facebook. Of course, one of its ads referenced Bollywood.

The timing seemed great, as India was just about to join in the smartphone boom that was already sweeping China. But, as we now know, India’s social media addicts love Facebook and WhatsApp instead.

It was the first of many overseas fails for WeChat.

July 2012: Voice and video calls appear

The new features kept on coming.

July 2012: Alibaba tries to kill off WeChat

Seeing WeChat as an eventual threat to its ecommerce empire, Alibaba launched a WeChat-esque social app of its own.

It didn’t take off.

But Jack Ma was right to be worried about WeChat as Tencent’s wunderkid app later ventured into online shopping, in-store payments, and a number of other areas that treaded on Alibaba’s toes.

Summer of 2012: Brands invade WeChat as QR codes swamp China

By the summer of 2012, a new trend was emerging: QR codes. QR codes everywhere. They’re very evident in China to this day.

Tencent opened up WeChat to brand accounts, prompting Chinese companies and foreign brands doing business in China to leap on board, keen to interact with China’s consumers in an arena that’s more direct and intimate than the nation’s other hot social network, the Twitter-esque Weibo.

Media outlets and celebrities also rushed to get their own WeChat public accounts.

To get people to add and follow a brand account, a company could display its personalised QR code anywhere and encourage shoppers to scan it. This is how QR codes became ubiquitous in China.

September 2012: Syncs with Facebook and Twitter

By now, WeChat has animated emoji as well as downloadable sticker packs. The app also allowed users outside China to connect their Facebook and Twitter accounts in order to find more buddies to add into the messaging app.

Facebook and Twitter are blocked in China.

The move showed that while some features were largely limited to the Chinese market – like the brand accounts – Tencent was still aiming at global expansion with a slimmed-down version of WeChat.

September 2012: Hits 200 million registered users

Its userbase doubled in the space of six months.

Late 2012: Backlash begins

WEChat had gotten so big that stories of terrible things happening through the app start to make national news in China. A woman was reportedly ambushed and murdered when a man who was stalking her using WeChat’s “people nearby” feature attempted to rob her.

That feature is switched off by default.

A few months after that attack, WeChat was implicated in the trial of a sexual predator who used the same location-based function to befriend and “groom” 160 boys, some aged under 13, who were living nearby.

December 2012: BlackBerry debut

Back when BlackBerry was still clinging on to relevance, Tencent came out with WeChat for BlackBerry. It made sense as part of its expansion into new markets with lots of young phone users where BlackBerry was still hip, like Indonesia and several countries across the Middle East.

A version for the doomed BB10 came later, in July 2013.

January 2013: WeChat caught censoring users around the world

WeChat entered the global limelight in the worst possible way when it was seen censoring users around the world who entered certain politically sensitive phrases into the app.

First reported by Tech in Asia, the development caused an international backlash against the app. It highlighted growing concerns of Chinese companies “exporting censorship” as they expanded overseas.

January 2013: 300 million registered users

The app reached 300 million devotees a few days after its second birthday.

February 2013: WeChat whacks Weibo

By now, it’s clear that WeChat had become huge and was threatening to surpass Weibo as China’s favorite social app, thanks to some help from its Facebook-esque Moments section.

Charles Chao, CEO of Weibo parent company Sina, conceded to investors that users were spending less time on Weibo.

February 2013: Hollywood glam

This was another threat to Weibo, which capitalized on the appeal of interacting in real time with big-name users. Stars such as Selena Gomez, John Cusack, Maggie Q, Paris Hilton, and the Backstreet Boys signed up to WeChat so as to engage with Chinese fans.

February 2013: Chasing after Indonesia

Just as in India, however, not much came of this, despite investing heavily in an Indonesian joint venture.

May 2013: A sign of progress in Thailand

Emulating the array of features and services being built into WeChat by companies in China, a major beverage firm in Thailand allowed customers to order water deliveries from its WeChat brand account.

In the end, however, Line and Facebook won the Thai market.

May 2013: Finally reveals figure for active users

WeChat had 190 million monthly active users.

A month prior, WhatsApp revealed it had 200 million. While WeChat seemed poised to be bigger than WhatsApp at the time, the US-based app – later acquired by Facebook – would ultimately steam ahead as WeChat failed to grow substantially outside China.

July 2013: Messi shoots

Back when WeChat still seemed to have a good shot as going global, the company hired footballer Lionel Messi. He served as WeChat’s billboard ad star and brand ambassador.

Lionel Messi’s WeChat billboard spotted in Hong Kong / Photo credit: Engadget’s Richard Lai.

August 2013: Payments and gaming gamble

With its latest update, WeChat added in social gaming integration as Tencent published a handful of its own games. Third-party games were later added to support WeChat’s Games Center.

In another big move, the app offered mobile payments. It was the start of the WeChat Wallet, which can be connected with a variety of Chinese-issued credit and debit cards. In time, these online and cashless in-store payments would expand to challenge ecommerce titan Alibaba.

August 2013: Overseas users flourish

Messi scored a blinder for WeChat, boosting it to 100 million registered users outside of mainland China. However, no active user count was provided.

To this day, Tencent has never updated this figure, leaving observers wondering if anyone outside China is using WeChat any more. Spoiler alert: they’re not.

See: WeChat’s global expansion has been a disaster

August 2013: Weibo launches rival messaging app

Aaaaaaaaand that’s the last we ever heard of it.

September 2013: WeChat vending machines

During a month-long experiment, 300 WeChat-branded vending machines popped up in subway stations in parts of Beijing. After this, a few other vending machine companies incorporated cashless payments via WeChat’s Wallet – as well as Alibaba’s affiliate Alipay app. They’re now a fairly common sight across Chinese cities.

November 2013: Xiaomi sellout

Selling stuff through WeChat is now common, so Xiaomi’s first experiment turned out to be a sign of things to come. Xiaomi sold 150,000 phones in less than 10 minutes in its WeChat-only flash sale.

January 2014: Taxiiiiiii!

WeChat started 2014 with another big push into mobile commerce. The partnership with Didi Dache (which would later merge with its main rival, Kuaidi Dache, and change its name to Didi Chuxing) allowed people to hail a cab and pay for it all within WeChat, totally without using cash. The move came days after Tencent contributed to a US$100 million funding round for Didi.

March 2014: Shopping shake-up

Tencent, which had been struggling with its scattered online shopping ventures over the years, took a big and drastic step – it bought a stake in Alibaba nemesis JD. This allowed Tencent to embed JD’s store into WeChat as the main shopping area.

It’s another direct taunt against Alibaba.

May 2014: WeChat stores

Building on the WeChat Wallet for payments, Tencent now allowed any business – whether major companies or small players – to open a store inside a WeChat brand account. This was exactly what Jack Ma was so worried about.

Image credit: Tech in Asia

June 2014: SMS nearly dead

SMS was declared pretty much dead in China mid-2014, with the average person sending just one SMS per day. (One wonders how many are actually just spammers.)

June 2014: Cash transfers

WeChat’s mobile wallet got even more useful, allowing people to send money to their buddies.

Summer of 2014: Forget apps

A new trend was emerging in China that year. Startups didn’t bother to build apps and were instead launching solely as a WeChat brand account.

“Users are increasingly spending more time within WeChat, time that’s taken away from other native apps. We are positioning ourselves in front of this trend,” a startup founder told as at the time. See the story here.

September 2014: Pay for your ice cream

In-store cashless payments have been on the cards since WeChat Wallet first appeared. They appeared for real this time, in conjunction with a handful of big-name chains, including Dairy Queen.

January 2015: Big brands buy ads

WeChat started 2015 with a big move to bring in more money. The ads appeared in the WeChat Moments feed, not in personal messages, allowing people to ‘like’ and comment on the ads just like any other Moments post. BMW and Coca-Cola showed the first ads.

Screenshots via Weibo

March 2015: Half a billion

WeChat revealed it ended 2014 with 500 million users each month.

March 2015: Uber blocked

Uber’s official brand account got blocked on WeChat, revealing a dark side to WeChat’s huge influence on social media activity in China. This deletion was a big blow to the US firm’s social media marketing and visibility in the country.

Many people cried foul since Tencent has a stake in Uber archrival Didi.

Tencent maintained that Uber’s account had violated the terms of service by offering deals or “enticing” users to share things with their friends. This is considered spamming in WeChat’s terms of service agreement.

Uber returned to WeChat shortly after, only to be removed again in December.

July 2015: Censorship slammed

Being a Chinese company, Tencent has to self-censor WeChat a lot. That’s how the media works there. A report by Citizen Lab showed the full extent of the political manipulation in the messaging app when its study revealed that 1.6 percent of posts made by brand accounts – like media outlets, brands, celebrities, and small companies – get removed after being posted.

Aside from all that, the report found evidence of censorship bots that block posts before they’re even published.

January 2016: WeChat used in courts

In a further sign of how pervasive WeChat is in life in China, some judges in the country are now using WeChat’s text and photo-sharing features during trials.

February 2016: Scanning China’s tourists

WeChat went global with its in-store payments service global as it sought to tap into China’s big-spending tourists. To do this, WeChat signed up stores around the world, so long as they’re ready to scan QR codes with their cash registers in the same way that’s done in pretty much every shop in China. The company’s push focused on areas that are hotspots for the nation’s outbound travelers.

Paying for Starbucks using WeChat in China / Photo credit: Tencent

Chinese tourists spent almost US$230 billion overseas in 2015, so both WeChat and Alipay were both chasing after such a big market.

Spring 2016: Tip your blogger

Reminiscent of those “buy-me-a-coffee” buttons seen some on some blogs, WeChat allowed bloggers and media outlets to collect tips from readers.

March 2016: 700 million

WeChat revealed newest figure for active users each month.

April 2016: Fake news

Keen to avoid the ire of regulators, Tencent clamped down on the spreading of rumors within WeChat. In addition, it issued rules aimed at banning clickbait headlines and “vulgar” content, soliciting shares and follows, flushing out spam, as well as prohibiting anything that “subverts” the state.

April 2016: No slacking

WeChat made a bold move into workspaces with the launch of its office chat app. Despite the inevitable Slack comparisons, WeChat Enterprise looks very different from the US-based startup and is focused on mobile.

Yet again, Tencent treaded on Alibaba’s toes as Jack Ma’s firm already has a growing workplace messaging app.

Summer 2016: Can’t take my eyes off you

WeChat accounted for 35 percent of time Chinese people spend glued to their phones, according to data from KPCB’s Mary Meeker.

The big three tech giants – Tencent, Alibaba, Baidu, in descending order – make up 77 percent of people’s time.

October 2016: Pedal power

Just as Tencent backed ride-hailing app Didi in its early days, the social media giant placed a bet on Mobike’s dockless two-wheeler service. Mobike got a further boost a few months later as Tencent baked the service into WeChat. Bike-sharing apps soon became a new facet of the unending Alibaba-Tencent rivalry when Jack Ma’s firm funded ofo, Mobike’s closest competitor.

January 2017: App store killer

WeChat started last year with a bang by launching “mini programs,” apps which require no download or install and which work only within the popular messaging app.

Google showed off a similar feature called Instant Apps for Android in early 2016, but it has yet to launch.

Major Chinese and overseas brands – from Didi to McDonalds, Dianping to Starbucks – had instant apps ready for the big public reveal. This is McDonald’s mini program devoted to coupons:

GIF credit: Tech in Asia

WeChat instant apps are an evolution of its brand accounts, which allow for online shopping and a wide range of other services.

With so many features possible, the new mini programs posed a challenge to Apple’s App Store and to the array of Android app stores popular in China. Could this be the future of apps?

April 2017: Leave your wallet at home

China’s smartphone owners are way ahead of everyone else on the planet when it comes to paying for things with their phones.

How pervasive is that in everyday life? Well, 45 percent of WeChat users paid in stores using the messaging app’s wallet feature because they don’t even carry cash. That’s according to a recent study by Penguin Intelligence. Not bothering to carry cash is the third reason cited for using WeChat to pay for their Starbucks or groceries – the speed and ease being the top two factors.

Although WeChat Pay was growing well, Alibaba’s Alipay spin-off seemed to be the market leader, as shown by a variety of metrics.

By now, WeChat had 900 million monthly users.

April 2017: Tipping infuriates Apple

It turned out that WeChat’s move a year earlier to let users to tip bloggers infuriated Apple.

Months of behind-the-scenes negotiations between Apple and Tencent resulted in the Chinese company being forced to direct its tipping through Apple’s own in-app purchase system, allowing the California-based company to take its customary cut of the action.

May 2017: Search engine launch

Not content with trying to kill off the app stores, WeChat was now threatening to topple Baidu, China’s leading search engine, Baidu.

It lets users trawl through WeChat brand accounts, articles, music, and more. With so much content posted to WeChat each day, including news from media outlets via their brand accounts, it’s basically an equivalent to the actual internet. So WeChat’s new search function made all that easier to navigate.

Welcome to the WeChat walled garden.

See: Cashless China: shoppers to spend $15t on their phones

November 2017: Never shutting up

WeChat’s chatty devotees set a new record, sending 38 billion messages per day. That’s 25 percent more than last year.

For a sense of scale, WhatsApp peaked at 55 billion per day at around the same time.

In addition, WeChat revealed in its annual report that it saw 6.1 billion voice messages – those walkie-talkie-style missives – sent each day, alongside 205 million video and voice calls. On the content side, there were 3.5 million active brand accounts.

November 2017: Nearly a billion

In the newest data available at time of publishing, WeChat has 980 million monthly users.

November 2017: Half a trillion

And that’s not the only huge number to grapple with. The ongoing success of WeChat – albeit just in one country – propelled Tencent to its highest ever valuation, reaching US$500 billion, joining the half-trillion elite alongside Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook, and Microsoft.

December 2017: Instant games

After starting the year with its instant apps shocker, WeChat ended it by rolling out exactly the same thing for games. One called Tiao Yi Tiao – a simple jumping challenge – immediately goes viral within WeChat. It looks like this:

GIF by Tech in Asia

Dubbed “mini games,” there’s actually nothing mini about them. They’re full-fledged games – made by Tencent as well as a variety of game studios – that you can play instantly without having to download.

December 2017: ID card

In a first for WeChat, one huge Chinese city has allowed its residents to store their national identity cards inside the messaging app. The ID cards are linked to WeChat using facial recognition.

The scheme is a pilot project in the southern city of Guangzhou, which has 14 million residents.

Winter 2017: Going underground

A number of cities started allowing riders to quickly scan their phones at the gate to pay for transport. As with shops, most subway systems are accepting both WeChat and Alipay.

Photo credit: IC

Guangzhou and nearby Shenzhen were among the first large cities to make this move, which looks set to percolate across the nation in the new year. Shanghai joined the fun at the start of 2018.

January 2018: We’ve got a file on you

WeChat got a rough start to the new year with reports that the app stores users’ chats as part of a system that snooped on what people were saying.

“WeChat does not store any users’ chat history. That is only stored in users’ mobiles, computers and other terminals,” the firm said in a post. “WeChat will not use any content from user chats for big data analysis. Because of WeChat’s technical model that does not store or analyze user chats, the rumor that ‘we are watching your WeChat every day’ is pure misunderstanding.”

However, the chat app continues to filter out messages related to sensitive political topics, a practice that was first exposed in early 2013.

January 2018: Making up with Apple

After last year’s falling out over WeChat’s in-app tips for bloggers, Apple and Tencent started the year with a reconciliation.

Now that Apple has altered its App Store rules to allow people to gift money to each other in apps without the iPhone maker taking a cut, WeChat’s Allen Zhang told media that a deal had been reached for the original tips function to be reinstated.

This article was originally published on the Tech in Asia website and was written by Steven Millward. Steven's interested in ecommerce, mobile, smartphone adoption, gadgets, social media, transportation, and cars. If you have any tips or feedback, contact him on Twitter: @sirsteven

The article was edited by Eileen C. Ang.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...