When Jimmy Song, a venture partner at Blockchain Capital, took to the stage at Consensus two weeks ago (wearing a black cowboy hat), he launched an attack on the blockchain-is-the-answer-to-everything mentality. He said, “When you have a technology in search of a use, you end up with the crap that we see out there in the enterprise today.”

Jimmy was clearly trying to be provocative and burst the bubble of blockchain fanatics, but he has a point. It’s not so much about blockchain per se (although this may be where the worst offences are committed) but about the focus on technology in general. Every day we are bombarded with articles about the need to digitize or about how [Blockchain/AI/APIs/Cloud/Mobile/IoT] will transform or disrupt such and such an industry. But we forget that technology in the absence of new business models never changed anything.

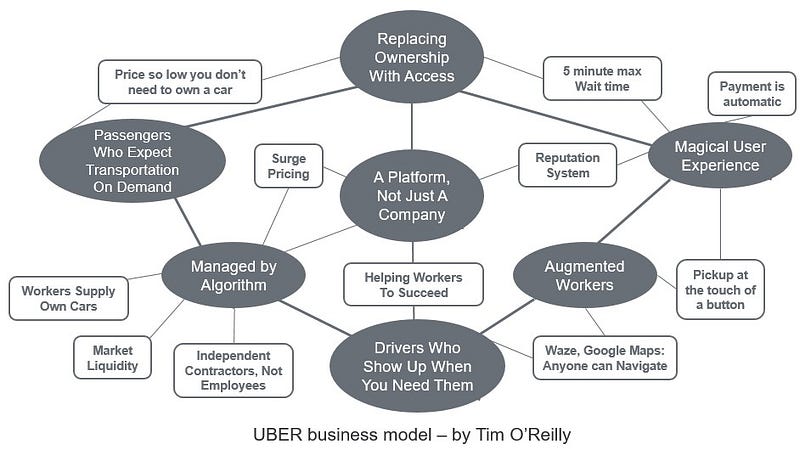

It wasn’t the internet that transformed retail or music. It wasn’t the smartphone that created Uber. Instead, it took business model change which exploited new technologies. In retail, it was the Amazon business model of one-click checkout, marketplace and next-day delivery. In music, it was the iTunes model of unbundling music to let us buy individual songs and then the Spotify rebundling model of all-you-can-listen streaming subscription service. And Uber didn’t just use the smartphone to let people order cabs (as many of the incumbents did), but instead uses the power of GPS to allow anyone with a car to become a taxi driver, transforming supply in the course of transforming user convenience and experience.

And so in banking we can safely predict that it won’t be blockchain or APIs or AI that transform the industry. Instead, it will be new business models empowered by those technologies.

Implementing technology without a clear plan risks making matters worse

In fact, we could probably go further and say that implementing new technologies without a clear idea of the future business model may make matters worse because it could well entrench existing practices.

The reason for this is that these new technologies will be implemented in support of existing business models rather than in pursuit of new ones. This means — as we have seen so often in banking — that digital technologies are used to digitize analogue products, rather than reinventing them for the digital age. But, it means more importantly that these technologies will be used to double-down on scale.

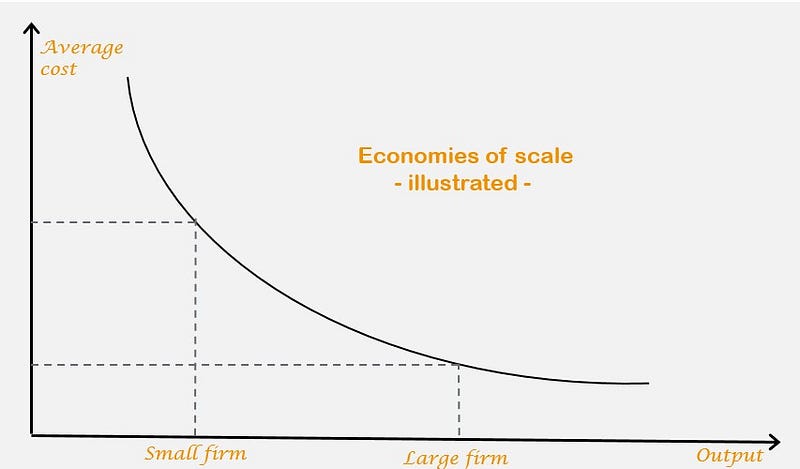

The industrial economy was all about scale. Once a company had come up with a winning product, the challenge was to exploit economies of scale as fully as possible. This allowed unit costs to be minimized and allowed firms to undercut rivals, seeing them gain more market share and scale and thereby locking in their leadership position. So all investments were aimed at maximizing scale — mass marketing, mass production, mass distribution — and business were organized into centralized, hierarchical structures to make this possible.

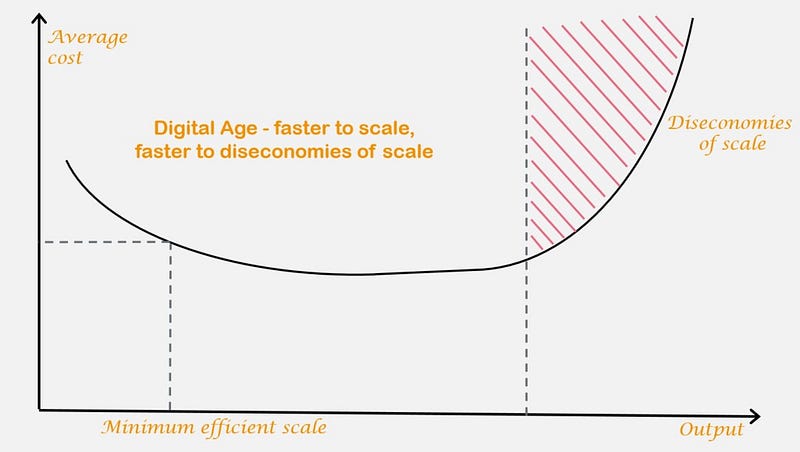

But these investments in scale in the digital age are quickly moving from sources of competitive advantage to sources of competitive disadvantage.

Technology and platforms have neutralized scale advantages

In their recent book, Unscaled, Hemant Taneja and Kevin Maney talk about how the technologies of cloud and AI have turned scale economies on their head.

In the world of cloud computing, IT resources are available cheaply to everyone meaning that — other than for the platform providers like Microsoft— scale doesn’t matter. A business can rent as little or as much IT as it needs, conferring little scale advantage in running massive operations.

But it’s not just IT resources, the same model is being applied everywhere. Take human resources, it is becoming increasingly easy to contract the people a company needs at the time they need them through platforms such as Malt and through a new breed of companies like Pangea, Digital Knights and WeDigitalGarden.

In economic terms, technology has lowered the minimum efficient scale of production to a point that is within the reach of most SMEs. And with a monolithic business structure, diseconomies of scale kick in sooner and are more material.

Artificial Intelligence is also having a profound impact on scale. If new technologies and platforms make it possible to manufacture profitably without scale, AI is making it possible to know what each and every customer wants — so that product and service can be tailored to everyone.

While the slight flaw in the unscaled argument is that more scale leads to more data and more data leads to better AI, it is nonetheless the case that any company offering undifferentiated products at scale will soon lose market share and scale. And so we see white space for new kinds of business models, where firms — or platforms — are able to take advantage of these new technologies to offer mass customization at scale.

The incumbents’ challenge

The incumbents challenge is, therefore, how to move away from this heritage of scale. This is likely a bigger challenge than it seems. Many companies in the industrial age missed shifts in consumer trends, but because of scale they could in many cases afford to catch up — copying rivals, buying rivals, etc.

In this digital age, the scaled business model is likely to lead to the double whammy of failing to spot new trends and the impossibility of catching up. Moreover, scale is so deeply embedded — across company structures, performance metrics, remuneration, processes, employee skillsets, cultures — that it will be so difficult for incumbents to make the transition.

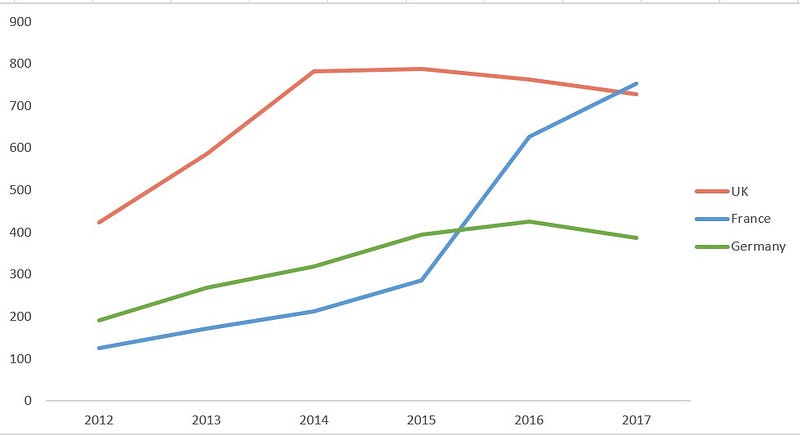

And it’s not just an issue facing companies. Take Germany, for instance. For so long, its industrial sector has been admired all over the world for consistently high quality engineering. But, the German economy is struggling to make the transition to the unscaled, digital world. It doesn’t (yet) have a vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystem from which the new unscaled models are emerging and the corporate structures and practices are very deeply ingrained.

But there is hope. We do see many incumbent companies, including in the banking industry, adopting new, unscaled business models for the digital age.

New banking business models for the digital age

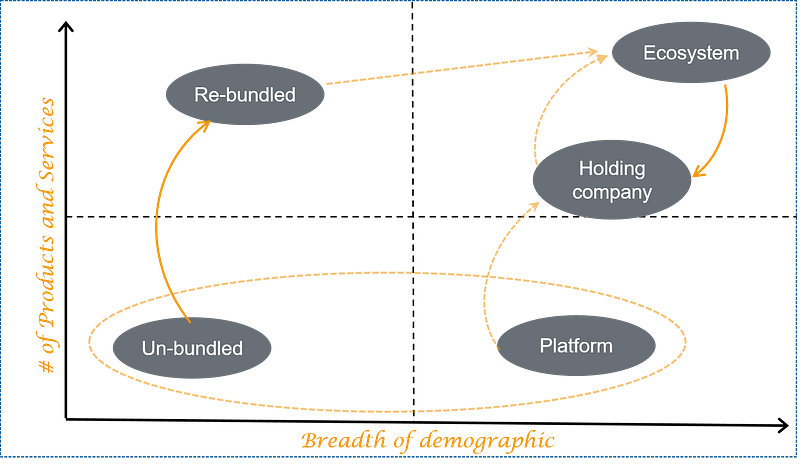

In many ways, the following section is an update to a piece I wrote two yearsago looking at how technology and new regulations, particularly PSD 2, were likely to lead to new business models. Where back then we identified 4 business models, now we identify 5 (but now fully discount the universal banking model as a relic of the industrial age). And where back then we framed the choices around asset intensity and profitability, we now frame the choices around the size of the demographic a firm wishes to serve and the number of products it offers to this demographic (although profitability is likely to improve in correlation with these factors).

Let us consider each in turn.

The unbundled start-up

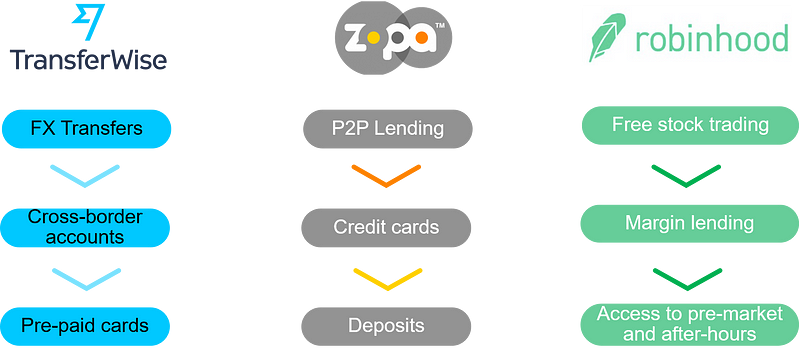

This is the model that most B2C fintech companies have pursued until now. They spot a niche, which could one of: a product that wasn’t previously offered (e.g Coinbase), a demographic that is un- or underserved (e.g Lending Club), a much better experience (with likely cheaper pricing), combining tech and design thinking (e.g Transferwise) or all of the above(e.g. WealthFront).

It is very much the embodiment of an unscaled model: using cloud infrastructure to operate at low volumes and using AI to serve small segments of the market. However, given it is both targeting a niche and targeting the consumer directly, it is often difficult to make this model profitable. The low infrastructure costs are more than offset by high customer acquisition costs which, because these tend to be single product companies, cannot be spread over many revenue lines. There are exceptions, of course, where the regulatory costs are low and the market is large (e.g WorldRemit), where there is a virality in the product design that lowers acquisition costs (e.g Revolut) or where the product solves a big issue in a big market such that it becomes a very large company (PayPal, M-Pesa, Stripe).

But the much more likely outcome is that successful unblundled start-ups start to bundle multiple products under the same brand.

The rebundled start-up

Once a start-up has found a strong product/market fit, it is logical for it to offer multiple products in order to boost its return on capital by cross-selling and upselling to its existing clients. It effectively moves from a single, unbundled product offering to rebundling a full banking service over time. However, it is different from a traditional universal banking model in a number of ways, such as the fact that it is digitally native but more importantly because it remains focused on serving the same demographic. In that sense, it doesn’t engage in mass marketing and production, but sticks to a narrow target market. Were it to begin to offer all products to all customers, it then risks becoming the victim of unbundling itself.

Examples of successful unblundled to rebundled start-ups include Zopa, Transferwise and Revolut.

The platform model

The platform model is somewhat of an anomaly in this list since it is essentially a scale play. However, it is likely to be an enduring model since:

1/ it is underpinned by strong network effects in a way that the universal banking model isn’t;

2/ it is often executed as part of an unscaled holding company strategy (see later); and,

3/ it is offered in the service of (and helps to make sustainable) the model of unbundled start-ups.

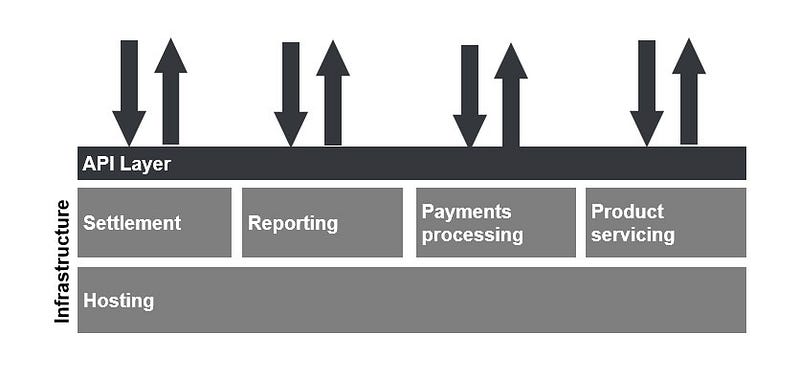

The platform model is simple. Banks rent out their back office as a service to others. For the unbundled start-ups who would be clients, it offers the advantage of not having to undertake a bunch of low value-added regulation and IT activities and it helps them to go beyond just renting IT infrastructure to renting IT applications and compliance. For the banks, it helps them to spread the largely fixed costs of IT and compliance over much larger volumes, improving economics.

The challenge, as pointed out in the last blog, is that this is a difficult model to scale across borders, limiting its profitability potential and meaning that there will be likely only one or two platform players per country/geo.

Examples of this model we have seen so far include Wirecard, Railsbank, Solaris and Bancorp. And it is no surprise that they are cropping up in the largest banking markets first where potential for scale economies is greatest.

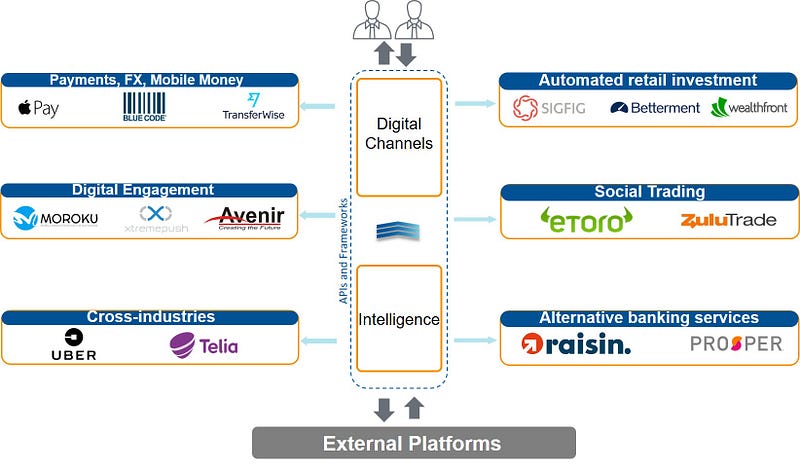

The aggregator model

The aggregator model is where a firm uses its grip over distribution to introduce the consumer to the right unbundled services. Effectively it uses AI and machine learning to understand the customer’s financial affairs and preferences and to anticipate their needs so that it can make the right service recommendations at the right time. With the introduction of PSD 2 — and similar regulation across the world — this model becomes easier to operate since it forces banks to share customer data. And, theoretically, it becomes possible to operate this model without engaging in any product manufacturing or without having a banking licence or any compliance team — as firms like Centralway Numbrs are trying to implement.

Nonetheless, our view — consistent with the blog from two years ago — is that this model will be thin, open but vertically integrated. By this we mean that aggregators will work with many different unbundled start-ups, but because of the nature of banking, they will likely manufacture some products — like current accounts that require a banking licence. And because of the need to deliver exceptional customer experience, they will end up having to become more vertically integrated. We observed the same thing happening in other industries, such as with Amazon and Netflix, and now we observe the same thing happening in banking. When unbundled fintech start-ups rebundle, they tend to become more vertically integrated — witness Transferwise’s move off the Currency Cloud platform or N26’s move off Wirecard.

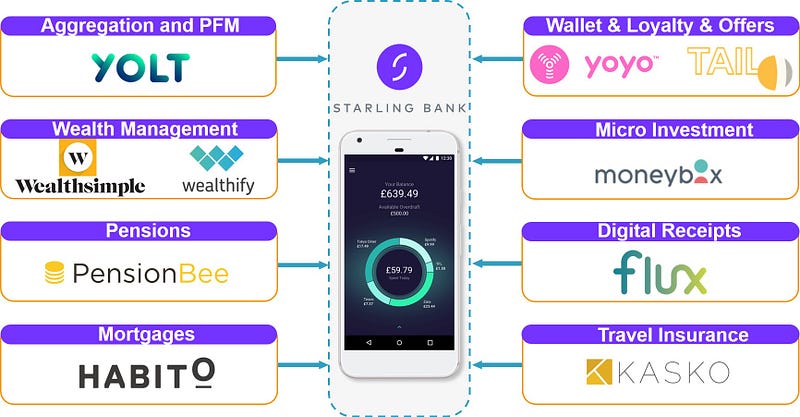

And so it is not a surprise that the aggregator models we are starting to observe in banking are thin and vertically integrated, such as M-Shwari and Starling Bank.

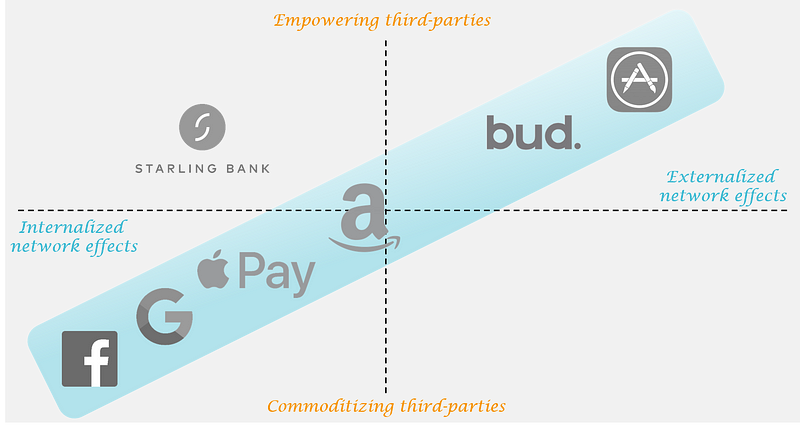

However, there are a couple of potential issues with the aggregator model. The first might arise from regulation. Will regulators allow banks that offer own-labelled services to aggregate services from third-parties and trust them to do so completely impartially? Especially given the marked tendency for aggregators to move from collaboration to competition over time. Moreover, there may be a business model challenge in that, as Ben Thompson observes so clearly in his recent post, models like Starling’s rely on third-parties while seeking to internalize the network effects, especially around data.

So, while we continue to believe that this is a sound model, aggregators of this type will need to look to empower the ecosystem by externalizing network effects and may seek to use arms-length intermediaries, like This is Bud, to avoid potential pitfalls around regulation.

And, where these potential issues are not addressed, aggregators leave themselves open to the threat from rebundled start-ups and from holding company models.

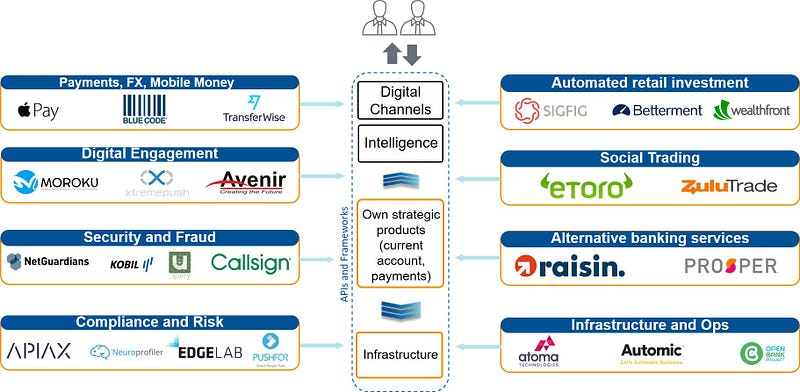

The Holding Company Model

The holding company model attempts to replicate the universal banking model — or conglomerate model in other industries — for the unscaled world and in a way that confers competitive advantage on the subsidiaries, especially by dint of network effects.

There is probably no “standard” for the holding company model. Berkshire Hathway is a great example of how a holding company structure can create competitive advantage across the group companies, in its case by using the cashflows and very low cost of capital of its insurance business to provide the cheap cash for investing.

Amazon is another great model to study and probably more relevant for banking. Jeff Bezos made a decision in 2002 to standardize the way information is shared across Amazon using APIs. It was a brilliant move in how to achieve control at scale. Essentially, the inputs and the outputs of every team were measurable in real time, such that their performance was instantly calculable and all other teams would get the information needed to conduct their work without bottlenecks, but it still allowed the teams autonomy in how to execute. The upside of this API model, so well documented in this post from Steve Yegge, was manifold:

- it allowed the different teams to operate autonomously so that that those business could be opened up to work with third-parties (as happened with AWS)

- It allowed each unit to be kept focused on its own KPIs, which essentially means that they are forced to remain close to customer trends. As Ben Thompson writes in another recent post, the genius of Amazon’s customer obsession is that it forces every part of the business to innovate at the same time as making it practically impossible to overshoot consumer demands.

- It critically allows every business unit to stay focused on its niche (essentially an unscaled model) but allowing for scale at a group level (e.g IT resources, distribution and brand), positive working capital flows, and the exploitation (internalization) of network effects across group companies.

This is what makes Amazon such a formidable company. It has figured out how to make the conglomerate model work in the digital age — through a holding company structure. And, furthemore, in its digital form, it overcomes one of the key shortcomings of its industrial age predecessor — it can achieve increasing returns to scale thanks network effects.

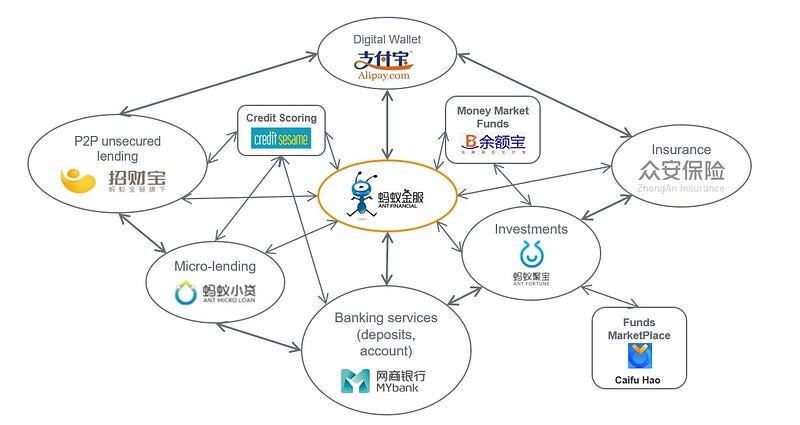

In the financial services space, the best example of this holding company structure is Ant Financial. Where Amazon has figured out how to adapt the conglomerate model for the digital age, Ant Financial has figured out how to recreate the universal banking model for an unscaled world. Its hub and spoke model sees the group leverage data, brand and distribution while the subsidiaries remain narrowly enough focused — on unsecured lending, investing, money market funds — to remain nimble and adaptive in the face of changing technologies and customer trends.

The Holding Company as a model for reinvention

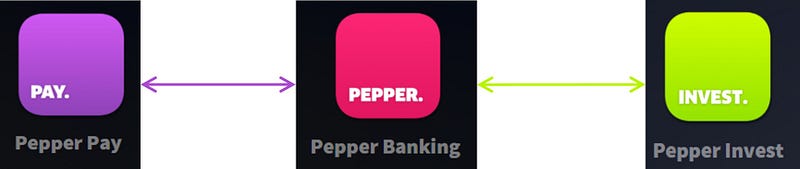

We see a strong trend in banking for incumbents to launch new digital banks. The examples abound, such as BNP Paribas’ Hello Bank. While this model to reinvention is in many ways sound — it allows these banks to transplant customers and trust into a new digitally native version of themselves — it risks creating another universal banking model, albeit one built on digital foundations. A better way of going about reinvention would seem to be a holding company model. This might be built on a Berkshire Hathaway model, as seems to be the case with Equitable Bank’s creation of its EQ Bank subsidiary, to create a sticky, low cost source of funds for its lending business. Or, probably more likely, it would be an Ant Financial model of having individual subsidiaries target different business lines, which is the approach that Bank Leumi seems to be taking with Pepper Bank.

Conclusion

There is a clear danger that with the constant hype around technology, banks miss the need to redefine their business models before embarking on major technology renovation. In fact, technology renovation in the absence of business model renovation may well make things worse because it would entrench existing business models based on selling undifferentiated products at the greatest possible level of scale. The digital age calls for something else — products, many of which will be new, targeted on specific demographics, made possible now thanks to technology change. In this blog, we have presented 5 models which would work in this new paradigm, of which the holding company offers perhaps the best route to success — especially for incumbent organizations looking to reinvent themselves.

Acknowledgment

The words are mine but the graphics were by Dan Colceriu.