Wired are really good at writing long, wordy essays on things they find of interest. I enjoy them, but not everyone has half an hour to read their musings. Therefore, as it covers my favourite FinTech firm Stripe, here’s a 1,500 abridged version of their 16 page, 5,000 word original (which you can read here).

The untold story of Stripe, the secretive $20bn startup driving Apple, Amazon and Facebook

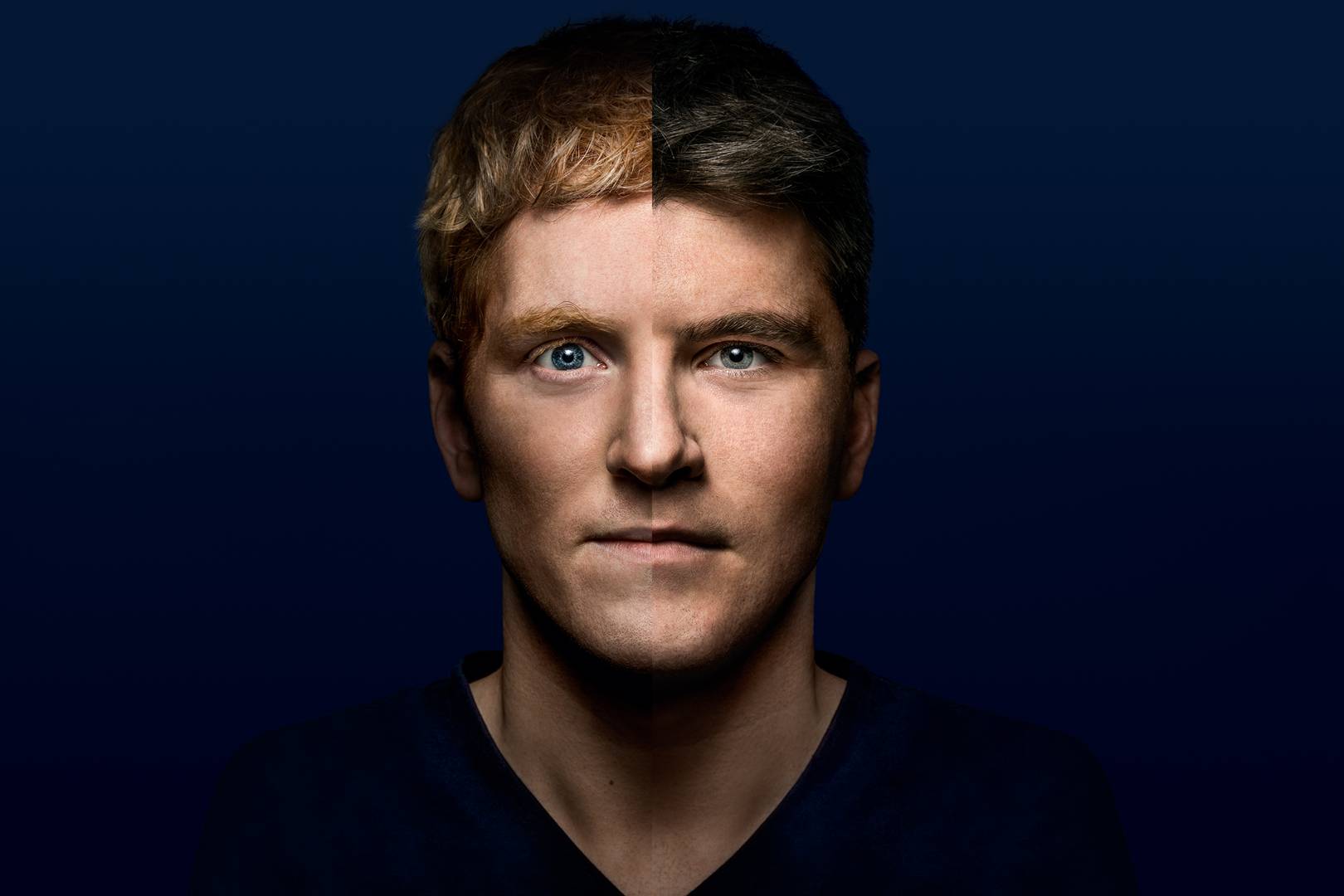

Patrick and John Collison have democratised online payments – and reshaped the digital economy in the process By STEPHEN ARMSTRONG

According to the World Bank’s Small and Medium Enterprise Department, there are between 365 and 445 million micro, small and medium-sized enterprises in emerging markets, contributing up to 60 per cent of employment and up to 40 per cent of national GDP. The main problem these companies face is access to finance. So how can entrepreneurs from emerging nations join the global market and help lift the wealth of their nations? One of the solutions comes from a small village in Ireland called Dromineer, of population 102 and the birthplace of the world’s youngest self-made billionaires, Patrick and John Collision …

[Dromineer] is where Patrick and John Collison, learned to code – and where they began to think about online payments. It’s where they began laying the foundations for Stripe, their payments company valued at $20 billion when it last raised money in September 2018 and which handles payments for Amazon, Booking.com, Lyft, Deliveroo, Shopify, Salesforce and Facebook.

“It was amazing to us that two kids in Ireland can start a business with customers around the world,” John explains … “What we did discover pretty quickly was that the hardest part of starting an internet business isn’t coming up with the idea, turning the idea into code or getting people to hear about it and pay for it. The hardest part was finding a way to accept customers’ money. You could share a photograph on Facebook but you couldn’t move money around in the same way. It felt like you were in the dark ages.”

In 2007, when the brothers were coding their APIs, online payments were supposed to have been solved. Elon Musk, Peter Thiel and Max Levchin founded PayPal in 1998, which was bought by eBay in 2002 for $1.5 billion. The fintech ‘revolution’ that followed, however, wasn’t much of an uprising but more of a spot of portfolio diversifying by some banks that laid down the payment rails any eager startup had to ride on. The banks still verified identity and owned the account for cards and payments drew from.

“The problem has always been the layers of intermediation,” explains Chris Higson, a professor of accounting at the London Business School. “The annual cost of financial intermediation in the US is roughly 2 per cent – the same as it was in the late nineteenth century. The US finance industry has showed no efficiency gains at all over 130 years” …

Paypal – designed to simplify payments – actually made this worse. The company infuriated startups with its restrictions – once turnover hit a certain level, Paypal automatically put the business on a 21 to 60 day rolling reserve, meaning that up to 30 per cent of a company’s revenue could be locked up for up to two months. Developers had to choose between this and complex legacy systems built by banks.

“For us it was quite visceral: these products are not serving the needs of the customers, so let’s build something better,” John Collison argues. “In old-fashioned legacy companies it’s the CFO choosing the payments system. They think all systems are alike, so they just sort the bids from suppliers. But if you’re a developer building the next Kickstarter, or the next Lyft, and you have a two-person team, both of you writing relatively complex code and solving complex infrastructural problem, you need a simple payments API that – once installed – doesn’t keep changing.”

In 2008, Patrick and John sold [their first start-up] Auctomatic to Canada’s Live Current Media for $5 million – making them teenage millionaires – then went back to university, MIT and Harvard respectively. They began tinkering with the idea of focusing on software developers – the people actually building the sites and apps. They came up with seven simple lines of code that anyone could insert into any app or website in a day to connect to a payments company. A process that used to take weeks was now a cut-and-paste job.

In 2010, the brothers dropped out of college and launched Stripe in San Francisco with seed funding from accelerator Y Combinator. The company offered seven lines of code and a promise that no other changes were needed. Developers who integrated the Stripe API wouldn’t have to touch it for years. In the early days, the brothers cycled to the office to save money. In 2011, they approached Peter Thiel and Elon Musk.

“It’s a little impetuous to go to PayPal founders and say payments on the internet are totally broken,” says John with a wry smile …

The two brothers pitched a vision of more internet commerce, driven by more connectivity and it being easy to use. “That had been the original vision of PayPal, but they hadn’t actually made it happen, so I think they got us, in a way that a lot of people didn’t,” John says.

Thiel led a $2 million series A round with Sequoia Capital and Andreessen Horowitz … [and] developers approved. Stackshare, the developer’s platform where companies such as Slack, Spotify and Opendoor post lists of every piece of software they’re using, has a running vote comparing Adyen, Braintree and Stripe. Adyen has 23 fans, is a favourite for 11 developers and has some 39 upvotes as of July 2018. Braintree does a little better with 130 fans, 29 favourites and 87 up votes. Stripe has 1,360+ fans, 170 favourites and 1,500+ votes.

In short order, Stripe signed deals with Lyft, Facebook, DoorDash, Deliveroo, Seedrs, Monzo, The Guardian, Boohoo, Salesforce, Shopify, Indiegogo, Asos and TaskRabbit. The company won’t disclose its payments volume but says it processes billions of pounds a year for millions of companies.

Over the past year, 65 per cent of UK internet users and 80 per cent of US users have bought something from a Stripe-powered business, although very few of them knew they were using it. Where PayPal injects itself into the checkout process, Stripe operates like a white-label merchant account, processing payments, checking for fraud and taking a small percentage: 1.4 per cent plus 20 pence for European cards and 2.9 per cent plus 20 pence for all others. The buyer sees the seller’s name on their credit card statement and, unless the merchant specifically chooses to deploy the Stripe logo, that’s all they’ll ever see …

On February 24, 2016 the company launched the Stripe Atlas platform, designed to help entrepreneurs start a business from absolutely anywhere on the planet. The invitation-only platform allows companies from the Gaza Strip to Berwick-upon-Tweed to incorporate as a US company in Delaware – a state with such business-friendly courts, tax system, laws and policies that 60 per cent of Fortune 500 companies including the Bank of America, Google and Coca-Cola are incorporated there for just $500.

That idea, in a sense, could only come from someone from a place as remote as Dromineer, Ireland, and with a clear sense of how it feels to be so far from the action. At its core was the ambition to “increase the GDP of the internet,” according to Patrick in his February 2016 launch speech at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona. Stripe, he explained, was targeting entrepreneurs from Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and parts of Asia. “A majority of the growth over the next ten years will come from underserved markets,” he explained. “That includes about 6.2 billion people we don’t reach yet, and that’s a huge missed opportunity” …

Today, 20 per cent of tech-based Delaware C-Corps started on Stripe Atlas … not everyone approves. “In a developing world context, Stripe Atlas has its benefits for disruptive SMEs located in the most conducive development markets and for those companies the business case is clear,” says Dr Nadia Millington, deputy programme director in social innovation and entrepreneurship at the London School of Economics. “However, the majority of SMEs cannot deal with the complexity associated with registering and maintaining a US C-company. Challenges include double taxation, onerous repatriation rules and an inability to establish control structures that are required to run multi-country businesses. The concept of the internet of the GDP is intriguing philosophically, but the underlying assumption that this will benefit a wide range of SMEs in emerging markets is a stretch. There’s a host of structural, institutional and social barriers which must be addressed in parallel.”

One solution is the platform model. Over the past five years, businesses including Amazon and Uber – all Stripe clients – have built multi-billion-dollar businesses at speed, disrupting industry after industry with a platform business model that’s open, connected and rapidly scalable, allowing them to create entire ecosystems of developers, customers and suppliers.

Platforms allow everyone to trade on largely neutral terms – connecting millions of sellers across the world. One in four marketplaces on Stripe pay sellers outside their home country. For the brothers, this is only the beginning. In July, Stripe entered the credit-card business – helping their business customers issue cards to employees using existing Mastercard and Visa rails. Their devotion to the founders of the internet means they’re out to rectify one horrible mistake made in setting the whole thing up …

When Berners-Lee and his team were building the world wide web and designing HTTP and HTMP standards, they included error codes such as “500: internal server error”, or “404: page not found”. In the early 90s, they were trying to realise [a] vision and setting out the rules for how we were all going to interact over this information network. One long-standing error code is “402: payment required”. The original intention – the reason 402 is reserved for future use – was that this code would be used to transact digital cash or micropayments. It has never been implemented – and the Collisons argue this is the reason tech is turning from an equal access opportunity to an oligopoly controlled by five companies now worth more than $3 trillion.

“The idea driving 402 was that it’s obvious that support for payments should be a first-class concept on the web and it’s obvious that there should be a lot of direct commerce taking place on the web,” says John “In fact, what emerged is a single dominant business model which is advertising. That leads to a lot of centralisation, because you get the highest cost per clicks and with the largest platforms. A big part of what we’re trying to do with Stripe is continually make it easy for new business to start, and for new businesses to succeed. Having commerce and direct payment succeed on the internet is a very important component of that. It’s the final piece in the Dream Machine.”

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...