Some of you may know that I write a monthly column for The Banker magazine, and have been doing this for almost twenty years! But The Banker goes back way longer than my column. In fact, it began in January 1926 when the first issue was published and is now almost a century old. Interestingly, since 1970 they've been tracking the world's biggest banks and the lists produced reflect the ebbs and flows of global trade. Editor-in-chief Brian Caplen looks back at these ebbs and flows as the magazine gears up for the fiftieth list in July this year.

Top 1000 World Banks ranking 50th anniversary

In July 2020, we will be examining how the ranking has developed since it was first launched in 1970 and, by so doing, we will track the huge changes the industry – and indeed the world – has seen during that time.

This is a story that has seen US, European and Japanese banks rise up and fall in the ranking, with Chinese banks writing the final chapter. It is set against a backdrop of stagflation in the 1970s; the advent of monetarist economic policies and privatisation in the West in the 1980s; the shift in economic power towards Asia; the rise of globalisation more broadly and, of course, the impact of the financial crisis.

The banking industry has expanded and changed radically over the past half-century as a result of changing customer demands, regulation and technology. The economic map of the world has changed in tandem. In 1970, when we started the ranking, China’s economy was one-tenth the size of the US economy and only the eight largest economy in the world, despite having the largest population. Now it is the second largest economy and equivalent to two-thirds of US gross domestic product (GDP).

Comparisons needed

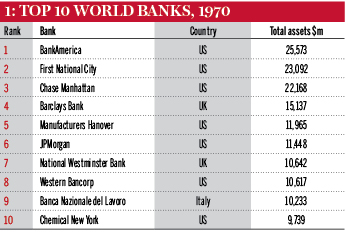

It is unsurprising, then, that when The Banker launched its first ranking of banks in 1970, the top 10 by assets (see table 1) was dominated by US banks (seven in total) with just a few European banks. Starting out with a list of 300 banks, the magazine’s editors justified the introduction of the ranking on the basis that international banking was growing fast. There was a need, they said, to make comparisons between different institutions from across the world – a concept that seems blindingly obvious now but clearly wasn’t so at the time.

“In recent years, banks have been expanding and proliferating at an unprecedented rate not only in the main financial centres but across national boundaries … because of these shifting patterns in world banking it is becoming increasingly essential to relate different institutions operating in one or more countries in terms of their size and weight,” they wrote.

The object was not to provide “a league table of performance”, they said, “still less to offer an index of efficiency” but to create a valuable tool for bankers engaged in inter-bank lending. Fast-forward 50 years and an essential purpose of the Top 1000 remains that of allowing banks engaged in international business – lines of credit, trade finance, payments, securities – to eyeball a counterparty’s figures to gain perspective on who they are dealing with.

In 1970, Bank of America topped the ranking with assets of $25bn. To give an idea of the massive growth in the industry, compare this with today’s top bank, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), which has assets of $4000bn, making it 160 times larger. This is over a period when world GDP has grown by only 25 times – showing how expansion in the banking industry has far outstripped economic growth.

Bank of America itself places sixth in the latest 2019 ranking measured now by Tier 1 capital (see table 10) with assets of $2355bn, making it about 94 times larger than its 1970 iteration on this basis. An interesting exercise with the 1970 ranking is to take stock of the famous banking names that have subsequently morphed into a new format or disappeared entirely as a result of consolidation.

First National City in second place was renamed Citibank in 1976 and merged with Travelers in 1998; Manufacturers Hanover in fifth place merged with Chemical Bank in 10th place in 1991. In 1995, Chemical Bank merged with third-placed Chase Manhattan and, in 2000, Chase with JPMorgan. In the 2019 ranking JPMorgan Chase places fifth, making it the largest US bank behind the four large Chinese banks: ICBC, China Construction Bank (CCB), Agricultural Bank of China (ABC) and Bank of China (BOC).

Communist conundrum

Chinese banks were not included in the 1970 ranking and this was, almost certainly, not a function of size alone but related to concerns as to how much sense it made to compare banks from Communist countries with those from capitalist ones. This was clear in the debate at the time over how to treat Yugoslav banks. “In general, domestic banks in Communist bloc countries are not included in the list because of their very different functions within the socialist economy,” explained The Banker’s editors.

“If they were included, it could be argued that the Soviet Gosbank [the Soviet Union boasted the world’s second largest economy in 1970] is larger than any commercial bank in the list. However, Yugoslavia is in a somewhat different position. The country is a member of the International Monetary Fund, and its currency is convertible. Therefore, leading Yugoslav deposit-taking banks which lend short-term are included.”

Over the next decade or two, closed Communist systems would be in retreat and the whole problem of how to treat ‘socialist economy’ banks was set to disappear. In 1979, the advent of China’s Open Door policy paved the way for the modernisation of the Chinese banking industry. Originally the Peoples’ Bank of China (PBOC) was the single state-controlled banking institution out of which three banks were spun off: ABC, BOC and CCB.

The PBOC was designated the central bank in 1983 and a year later its remaining commercial activities were transferred into the newly created ICBC. By the end of 1991 the Soviet Union had collapsed and commercial banking models emerged in nearly all the former bloc countries.

Expanding ranking

In 1980, The Banker expanded its ranking from 300 to 500, arguing that “at a time when more and more financial institutions are undertaking full commercial banking business and when many medium-sized banks are becoming increasingly active on the international scene, a list of only 300 banks would have been restrictive”.

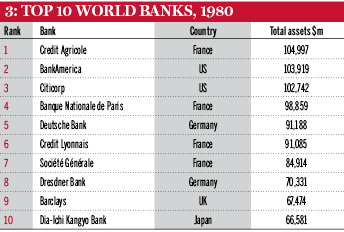

There are two standout features of the 1980 top 10 (see table 3): the dominance of European banks over US ones and the fact that the editors regarded a 17% asset increase as a growth slowdown.

French banks put in an especially strong performance, with Crédit Agricole placed first with assets of $105bn – more than four times higher than the figure that gave Bank of America the top spot a decade earlier – BNP stood in fourth place, Crédit Lyonnais sixth and Société Générale seventh. Bank of America and Citi flew the stars and stripes in second and third places, respectively, and Japan’s Dia-Ichi Kangyo Bank held the number 10 spot, but apart from this the 1980 Top 10 was a European list.

The Banker’s editors commented: “The nationalised nature of the ‘big three’ French banks (BNP, Crédit Lyonnais and Société Générale) is apparent from their remarkably low ratios of capital and reserves to assets less contra accounts (1.40, 1.22 and 1.65, respectively); their ratios of pre-tax earnings to average assets less contra accounts (0.16, 0.27 and 0.37 respectively) underline their significantly lower profitability compared to other banks of a similar structure.”

Nationalisation of the French banks had taken place under the 1945 government of general Charles de Gaulle but only a few years after the preceding comments by The Banker, the 1984 banking law paved the wave for deregulation, leading on to privatisation in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Crédit Lyonnais ran into trouble in 1993 and had to be rescued, with Crédit Agricole acquiring sole ownership in 2003.

As always, currency values and inflation rates played their role in the banks’ positioning in the table. Dollar weakness in 1980 mitigated against US banks while UK banks grew by 38% in dollar terms. With that rate of growth, Barclays found itself in ninth position but this, remember, is the era of stagflation that would be met with the monetarist response later in the decade under the administrations of Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US. This being the case, The Banker notes that “the growth of the big four UK clearers” is in part explained by domestic inflation of 18.4% and an 8.68% strengthening of sterling against the dollar.

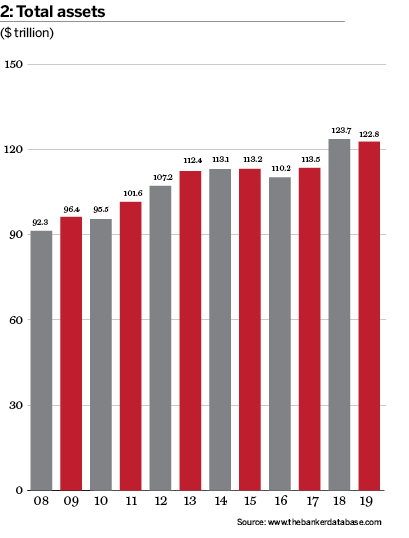

Less surprising, then, that in this environment a 17% increase in assets for the Top 500, down from 35% the previous year, was regarded as a slowdown. For the top 10 banks in isolation, the equivalent figure was 18.1% down from 32.1%. By comparison with today, combined asset growth of the top 10 banks between 2018 and 2019 was 1.2% and for the Top 1000 overall; even the largest jump since the financial crisis in the year to 2018 (see table 2), worked out just below 9%.

Japan rides a wave

While a huge amount of industrial restructuring was taking place in the UK and the US during the 1980s, leading to high unemployment and a general economic malaise, Asia was starting to emerge as the growth centre of the world. Among the large economies, Japan emerged as the growth leader between 1985 and the early 1990s.

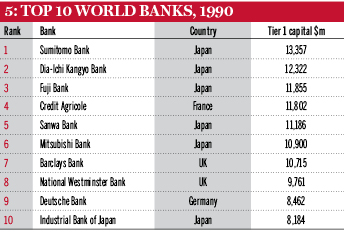

Hence, The Banker’s Top 10 for 1990, now ranked by Tier 1 capital, was very much a Japanese affair (see table 5). Sumitomo Bank came top with other Japanese banks in second, third, fifth, sixth and 10th positions. Crédit Agricole hung on to fourth place, the UK’s Barclays and National Westminster (now part of Royal Bank of Scotland) were seventh and eighth, respectively. Deutsche Bank came in ninth while US banks were conspicuous by their absence.

The Japanese asset bubble was, however, destined to end in an almighty bust in late 1991 and early 1992, from which the economy is still struggling to recover even in 2020. Property prices went so crazy that at one point the land of the Tokyo Imperial Palace was reckoned to be worth more than the entire state of California. At the end of December 1989, the Nikkei stock market index hit a record 38,916; today it has finally crawled back to 24,000.

The Banker, by now ranking 1000 banks based on Tier 1 capital (which remains the standard format), reported: “Many of the world’s top banks enter the 1990s with profitability still falling and generally lower margins and capital ratios. But there is still plenty of action in Japan and east Asia.”

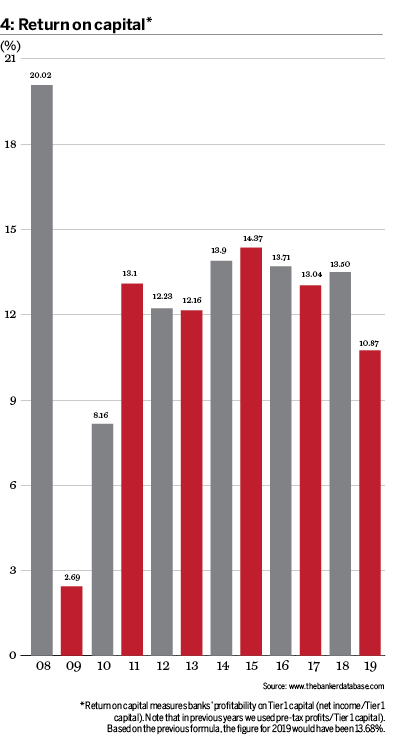

Profitability being a relative concept, The Banker’s editors complained in the July 1990 edition that the average rate of return on capital “[that] used to hover around 20% in the 1970s and 18% in the mid-1980s … last year fell from 18.61% to 14.15%”. These days, a 14% return on capital would be considered a glorious result for many of the world’s largest banks. Table 4, showing returns on capital before and after the crisis, illustrates that the 2008 figure of 20% was, in fact, a warning sign of troubles ahead. The ratio fell to 2.69% in 2009 and climbed back to a high point of 14.37% in 2014 before falling back in subsequent years.

Japan’s banks, like American ones before them, went through a period of consolidation so that in 1998 second placed Dia-Ichi Kangyo merged with Fuji Bank (third) and the Industrial Bank of Japan (10th) to form Mizuho Financial Group, which placed 17th in the 2019 ranking. Mitsubishi Bank, in sixth place in 1990, joined forces with Bank of Tokyo in 1996 and the resulting group merged with UFJ to become Mitsubishi UFJ in 2005. In 2019 Mitsubishi UFJ appeared at number 10 in the ranking. UFJ itself was formed in 2001 out of a merger between Sanwa (fifth in 1990), Tokai Bank and Toyo Trust and Banking.

Advent of globalisation

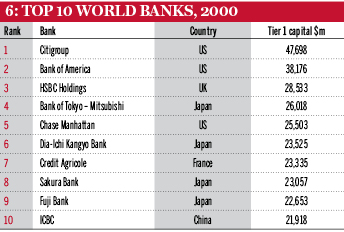

By 2000, globalisation was in full swing and The Banker’s top 10 was looking more geographically balanced, with three US banks, two Europeans, four Japanese and, very significantly, a Chinese bank, ICBC, in 10th place (see table 6). The UK’s HSBC in third place was, at that time, very much the standard bearer for globalisation, having acquired Midland Bank in the UK in 1992 followed by major acquisitions in South America to add to existing franchises in Asia and the Middle East.

This was also a time of high profits and The Banker reported: “Banks around the world are more profitable than ever. The Top 1000 world banks in the past year produced total pre-tax profits of $309.7bn, a whopping 77.6% increase on the previous year and $90bn more than the previous record in our 1997 listing.” Citigroup, in first place by Tier 1 capital, saw its profits rise 72.1% to $15.9bn, more than 5% of total profits for the Top 1000.

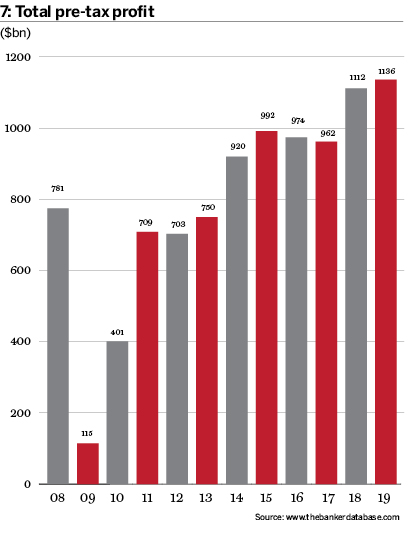

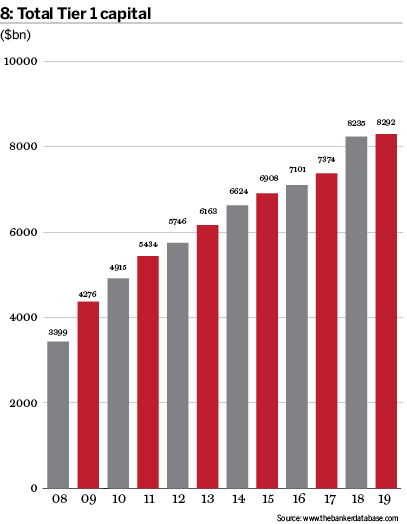

Profits fell back a bit in 2002 and 2003 but then carried on rising until the financial crisis. As table 7 shows, profits have recovered from a crisis low of $115bn to reach a record $1136bn in the 2019 ranking. But, happily, Tier 1 capital has been on a similar trajectory (see table 8), so it would be wrong to conclude that we are again in dangerous territory, at least as far as the banks are concerned. Interestingly, in a similar fashion to those of Citi 20 years previously, the current leader ICBC’s profits account for nearly 5% of the Top 1000 total.

Profits and returns have shifted eastwards over the past two decades and the 2007/08 financial crisis reshaped banking but both effects took time to show up in the ranking. By 2010 (see table 9), ICBC had moved up to seventh place in the top 10 but was still the only Asian bank. US banks occupied the first three places, with Bank of America back at number one just as it was 40 years previously.

Winners and losers

For the most part, the financial crisis led to consolidation around the existing leaders, giving them an even more dominant position than previously – clearly creating a regulatory headache for regulators since they have become, in the jargon, ‘too big to fail’. In the case of Wells Fargo, its snatching away of troubled Wachovia from Citi at the 11th hour, combined two large US banks (Wachovia placed 19th and Wells Fargo 23rd in the 2008 ranking) and accelerated it up the ranking to the sixth position (in 2019 it placed seventh).

Moving in the other direction, but at quite a slow speed, was Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), which placed fourth in 2010. In 2007, RBS (now renamed NatWest) was part of a consortium with Spain’s Santander and Belgium’s Fortis, which bought Dutch bank ABN Amro. This helped RBS move up to third place in the 2008 ranking and gave it the number one spot ranked by assets. With $3808bn in assets, RBS was 28% larger than the second placed bank in the asset ranking, Deutsche Bank. More than a decade later the assets of ICBC, the largest bank in the ranking, are only 6% larger than RBS’s were back in 2008.

This neatly illustrates the problem with using assets as a banking measure as there is little indication of their quality. For this reason, we have opted for Tier 1 capital to organise the ranking. RBS expanded too quickly, acquired lots of bad assets and ended up in government ownership, following which it restructured and sold off assets, thus turning a global and investment banking franchise into a domestic retail and commercial bank. This was reflected in its current position in the ranking. In 2019, RBS placed 41st with $879bn in assets – slightly less than one-quarter of its peak size.

Santander, by contrast, did much better out of the deal, getting assets in Brazil and Italy and selling on the latter at a profit weeks after the deal closed. Santander placed ninth in 2010 (see table 9) with $82bn in Tier 1 capital and then set about consolidating its gains so that today it has an only slightly larger $89bn capital base and stands in 15th position.

The dragon wakes

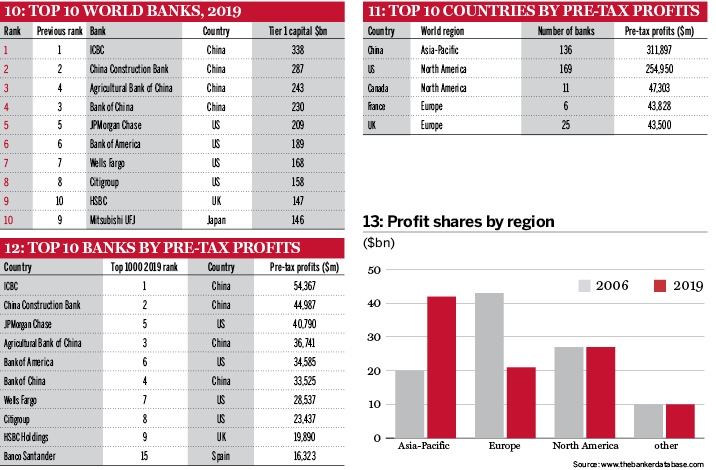

The final chapter in this story is the arrival of the big four Chinese banks at the top of the ranking. In 2011, ICBC was sixth, CCB eighth, BOC ninth and ABC 14th (up from 28th). In 2019, they hold the top four places, followed by the big four US banks, with HSBC at ninth and Mitsubishi UFJ 10th (see table 10). There are 136 Chinese banks in the ranking and China heads the table of bank profits by country (see table 11) with its banks making nearly one third of global profits. In a table of individual banks by profits (see table 12), ICBC and CCB are first and second with ABC fourth and BOC sixth.

Economic power has shifted East over the past 50 years and banking strength has followed, especially in the past 15 years. Table 13 shows profit shares by region comparing 2006 before the crisis and 2019. While North America’s share has remained constant at 27%, Europe and Asia have more or less swapped places, with Asia’s share increasing from 20% to 42% and Europe’s falling from 43% to 21%.

The banking landscape has changed dramatically but where are we headed next? Will Chinese banks maintain their grip on the ranking or will they lose their dominant position to banks from a different region in due course, just as happened to Japanese, European and American banks?

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...