Carl Howard asked me to look at the challenger and neobanks we discuss today and those of twenty years ago …

Have you ever done a piece comparing Smile, IF and FD with latest challenger banks. The cynic (cynic moi?) in me feels intuitively there's an interesting story there.

— Carl Howard (@carlfhoward) August 18, 2020

If you’re not aware, there was a huge rise of internet banks in the late 1990s. There was a Gay & Lesbian Bank in the USA and a David Bowie Bank for old farts like me. Britain was a breeding ground for such new banks with the launch of Smile by Co-operative Bank, Intelligent Finance by Halifax, Egg by the Prudential and Cahoot from Abbey National (now Santander).

These all emerged in the early 2000s and were welcomed.

UK bank customers have rarely had it so good. Courted by a raft of new banks, they are being lured with discounted mortgages, high interest rates and a promise of 24 hours a day, seven days a week service.

This is a very crowded market place... and a great time for consumers. But there are a few catches. For one, the more spectacular rates are available only on the internet. For another, some banks are picky, choosing only rich customers with a good credit history. The biggest worry, though, is for investors in the new ventures: Can all the internet and telephone banks ever make a profit …

Andrei Ilyin, a banking analyst with Nomura International, warns that this strategy works "only in theory - if customers are acting rationally and show no inertia".

In the real world, the big flow of customers has yet to materialise.

People, fearing the hassle, are reluctant to switch accounts.

The little things irk: Who wants to pay postage for mailing in a cheque, when it can be dropped off at a local branch on the way to work? What about the call charges to service centres and for internet access? And there are bigger worries, says Nomura's Andrei Ilyin. And some customers simply want to have the option to go to a branch and talk to a human being.

I guess, when I read these reports from twenty years ago, I realise that the idea was sound: shift people to online self-service banking; but the timing was wrong: we were still using dial-up lines in 2001 and a mobile phone just made telephone calls.

Twenty years later, the timing is much better but is it still right? I’m not sure. I still see stats that people don’t trust mobile apps and online banking. Sure, the pandemic has shifted those customers fast to download such services:

Between 14 March and 14 April, 200,000 people downloaded their bank’s app each day, according to data collected by fintech firm Nucoro. In total, six million people—or 12% of the UK’s adults—have made the switch to digital banking in recent weeks.

But are they committed? Are these the real new accounts? And what constitutes a real new account? It’s not the one my salary is paid into. So, what is it and why did the swathe of challenger and neobanks of the 2000’s fail?

On the latter side, I’d say the issue was sub-brands launched by mid-size financial firms at a time when the customer was not ready for the technology. There’s three issues here: one is the launch of a sub-brand; the second is the timing; and the third is the cost.

On the first one, most banks fail when they launch new brands. Just look at Bó from RBS or Finn from JPMorgan Chase. These are new entrants that were withdrawn within a year of launch. What usually happens is that the politics takes over internally, as the new brand starts to cannibalise the old brand. There are other issues too: the new bank drains resources, challenges internal structures and thinking, demands attention and creates friction. For these reason, most new banks launched by old banks only succeed if they’re targeting virgin markets. That’s why ING Direct worked and, you might say, why First Direct succeeded.

First Direct was launched in 1989 by Midland Bank, now HSBC, and has been a frustrated child of the big bank group. It tends to be that the parent company uses this child to play with ideas but the one thing overall about why First Direct succeeded, unlike Smile, IF and Cahoot, is that it was a pure-play telephone bank, not an internet bank.

That leads to the second point: timing.

When First Direct launched the timing was right for telephone banking. Rotary telephones – most of you won’t remember those – were just transitioning to pulse dial telephones and people liked the idea of talking to a human from home, especially as bank branch hours back then were limited from 09:30-15:30.

It made sense.

Internet banking at a time when people didn’t trust the internet didn’t make sense. Hence, the first wave of challenger banks failed with litmus test of user acceptance.

Finally, on cost, the marketing magazine Campaign articulated it well back in 2001:

The obvious reason to avoid establishing a purely online brand is the cost of setting it up and operating it. "There are lots of problems associated with being a start-up," Richardson points out. "It has been a lot tougher than the start-ups had expected, because traditional brands are still very powerful."

Barclays had the experience of its b2 project to guide its decision about its web offering. Launched as a sub-brand for online and phone ISA and unit trust investments in 1998, b2's closure was announced at the start of 2001. "It did have an effect on our strategy," admits Richardson. "The expense of establishing a new standalone brand was a key factor."

Is this still true today? Some would say no, it can all be viral, but just take a look at Marcus from Goldman Sachs.

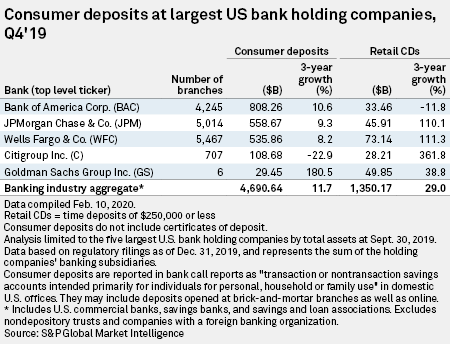

My friend Ron Shevlin estimates that Goldman Sachs spent $80 million on advertising Marcus in 2017 and over $100 million in 2018. Cool. And that got them almost $30 billion in consumer deposits, about 0.65% of the US mainstream market.

Source: SPGlobal

As mentioned on Monday, the main UK challengers are challenged with deposits too:

Collectively, the three challenger banks held £4.8 billion of customer deposits at the last count. That still makes them very small. By comparison, Virgin Money, one of the previous crop of “challenger” banks, has around £64 billion in customer deposits; and Metro Bank has customer deposits of £14.5 billion [Lloyds Banking Group has £250 billion].

Are things different now? Can the challengers win without major investments in marketing? What about their deposit to loan ratios? Will they ever be profitable?

These are all good and valid questions as the original wave of challenger banks consistently gained good grades for service, but never gained market share dominance or really challenged. Is it truly different today?

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...