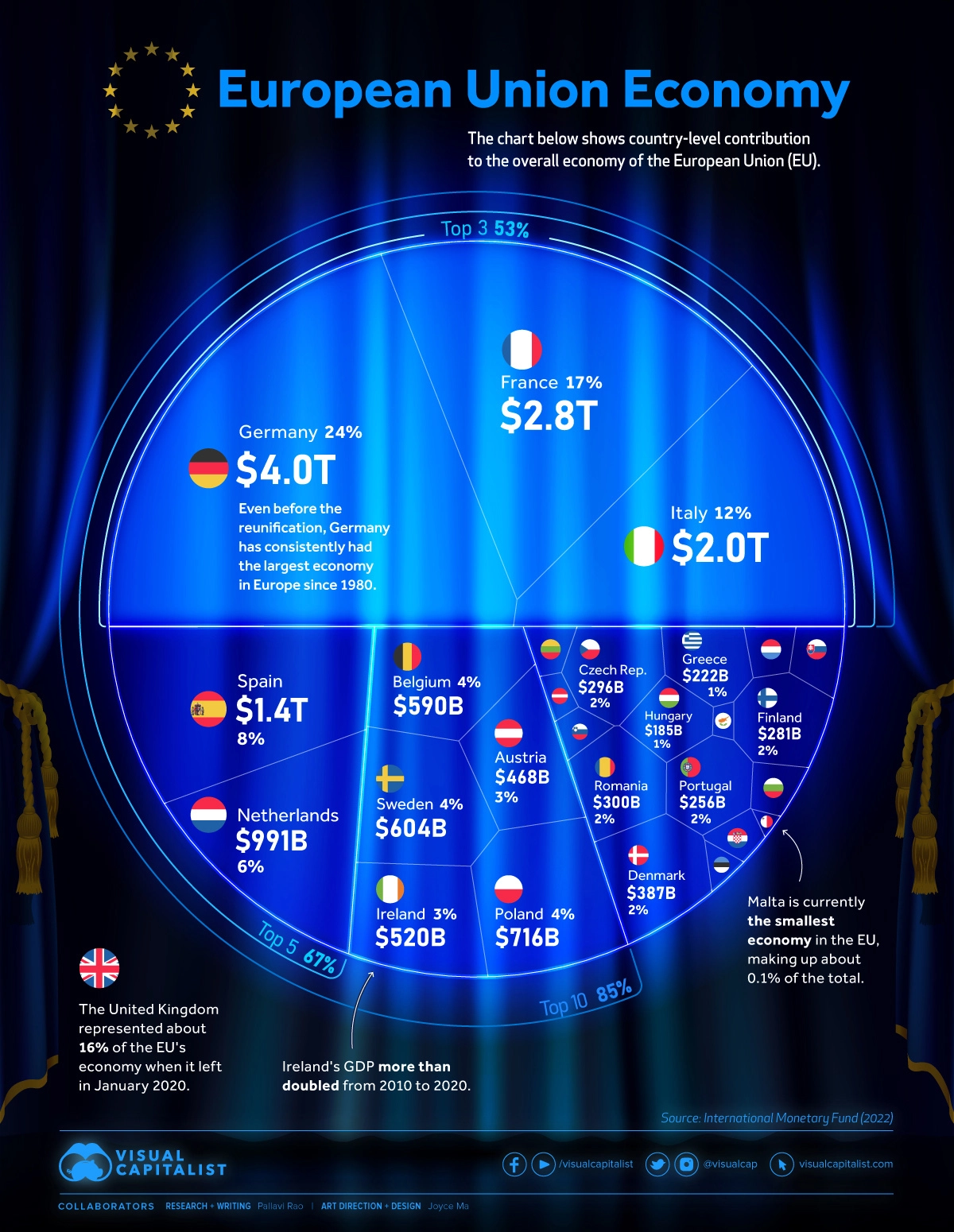

Why am I writing about Poland? First answer, because I am married to a Polish lady. We met in a night club where she was on the dancefloor … I’ve always been attracted to Pole dancers. Second, because I moved to Poland five years ago and it is a fascinating country. One of Europe's fastest rising countries - it is the sixth largest economy after Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands ... and rising fast into Pole position.

Source: The World Economic Forum

... it is actually a great place to live, as evidenced by Dominik who I met recently. Dominik Andrzejczuk is actually a Polish-born American, who is heavily involved in tech and start-ups. He spent years in California and, five years ago, came back to Poland. His story intrigued me so we had a chat on the record the other day.

Here it is and I hope you find it interesting.

Chris: Tell me about yourself Dominik.

Dominik: I was born in Poland, but my family emigrated when I was less than a year old. Although I have Polish roots, I largely identify as an American: I watch American football, follow baseball, and enjoy other typical American pastimes. Growing up, I lived in a Polish neighborhood in Philadelphia. My parents and I resided in the US without legal status for six years until they were fortunate to secure green cards through the 1995 lottery. We chose to stay in the US, and my father, originally a farmer, self-taught programming and landed a stable job, truly embodying the American dream.

After high school, I attended Villanova University where I majored in physics. Upon graduation, I founded my first company in the mobile payments sector, which eventually led me to relocate to California. An investor from Sunnyvale believed in my vision and invested $150,000, propelling my career in tech. By the time I moved to California in 2010, I lived in San Francisco for a mere $500 or $600 a month, a rate that seems unimaginable today. Back then, San Francisco had a noticeable homeless population, although it wasn't as pervasive as it has become today. It felt like a golden era, especially before major tech companies like Facebook and Twitter went public. My journey in the tech world didn't stop there; after my initial company, I had the opportunity to meet one of the co-founders of Yahoo.

A few years after he launched his venture fund, they approached me, noting that my software and technical background could be a valuable addition to their small team. Thus, I joined this venture capital firm. During my time there, we made an investment in Rigetti Quantum Computing of Berkeley, one of the pioneering startups in gate-based quantum computing. My involvement with this investment ignited a passion for quantum technology. I had the privilege of working directly with Chad Rigetti, the company's founder, and delving deep into the emerging realm of high-performance computing.

Around 2014-2016, the political climate in the US began to shift, especially with Trump announcing his candidacy and eventually securing the presidency. San Francisco's environment started feeling different, with a palpable ideological tension.

While I became increasingly keen on exploring more investments in the quantum realm, my partners felt that our stake in Rigetti sufficed. Seeking more opportunities, I researched quantum computing hubs and discovered that much of the groundbreaking work was happening in Europe, particularly in Poland. My ties to Poland were already strong. Starting from 2013, I had been visiting Poland every summer, spending significant time there and connecting with tech professionals. I observed a remarkable pool of technical talent coupled with a relative absence of business acumen. My reasoning was straightforward: with such a reservoir of technical expertise, importing softer business skills like sales and marketing might be a feasible strategy to harness this potential. This realisation, over time, played a crucial role in my decision to relocate to Poland in 2018.

By 2019, I established my own venture fund, Atmos Ventures, in partnership with the Polish Development Fund PFR, marking the commencement of my professional journey in Poland. In 2020, I backed two quantum computing startups originating from Oxford University, yet deeply linked to Polish academia and talent. One of these, Oxford Ionics, collaborated closely with the Polytechnical University of Warsaw for their control systems. The other, ORCA Computing, had a product lead, Kris Kaczmarek, who was the brain behind their core technology. I began to notice a recurring pattern: many leading figures in quantum computing had Polish roots, even if they were operating outside of Poland. This trend solidified my decision to stay and continue my work in Poland.

As I settled more into Warsaw, I began closely monitoring Poland’s GDP and growth trends. I moved to Warsaw in 2018, right when I noticed a significant upswing in the real estate market. That year served as a pivotal moment, marking rapid growth. Over the past five years, I've personally observed Warsaw's impressive development. Being situated in the Wola district, near landmarks like the Warsaw Spire, since 2018 the neighborhood is indistinguishable to when I first started living there. When I initially relocated in 2018, the landscape was dominated by construction sites and mud, indicating a region in the throes of transformation. Once a rough neighborhood, it's now among Warsaw’s most sought-after areas, underscoring the dramatic change I witnessed. The growth momentum shows no signs of waning, especially with major tech firms investing heavily in the country and many professionals, either natives or those who studied abroad, returning to contribute to its progress.

Subsequently, rather than pursuing another investment fund, I founded my own Quantum Computing, QDC. I had cultivated a vast network of exceptionally talented individuals involved in cutting-edge technology. My primary objective was to bridge these experts with business challenges in the US, focusing on solving large-scale optimisation issues and harnessing the talent from Poland. That's the journey that has led me to where I am today.

Chris: I've seen exactly what you've seen, which is the development in Poland in the last decade in particular. When you look at Warsaw, it amazes me now is how many tall buildings there are now, which there weren't a decade ago. They weren't even there five years ago.

Dominik: It is becoming a very self-sufficient country. It's the fourth largest economy in Europe.

Chris: One of the things that you touch on is the fact there's so much talent here. How has that happened? How has that talent evolved or what was the reasoning behind why there are so many educated people?

Dominik: In the realm of quantum computing, one of the key aspects I've noticed is how Poland has nurtured its talent through investments in education and promoting entrepreneurship.

A close friend of mine, who works at NVIDIA in Santa Clara, introduced me to a team focused on expanding in the central and eastern European regions. They're keen on significantly investing in this area, with Warsaw being a prime target. Despite having an office there for a while, one feedback that resonated was their admiration for Polish machine learning developers. For those familiar with machine learning, its core revolves around statistical analysis, essentially linear regressions, a topic typically covered in an introductory calculus class. What sets Polish developers apart, according to my friend, is their deep-rooted understanding of foundational mathematics such as calculus, differential equations, and linear algebra.

In contrast, many machine learning engineers in the US tend to be trained narrowly, focusing mainly on algorithm implementation without a comprehensive grasp of the foundational math behind it. This often necessitates pairing them with math PhDs to create more robust AI algorithms. However, in Poland, many machine learning developers inherently understand this underlying mathematical theory.

A personal anecdote further highlights this disparity in educational systems. While I was in high school, I took an advanced placement physics class, equivalent to a college-level course. Once, when I sought my father's help with homework, he was surprised, mentioning he had covered similar concepts in his 8th grade maths class. This experience underscored for me the differences in what's considered advanced in the US compared to what he had experienced in his early education in Poland.

When I lived in California, I observed an educational trend referred to as the "Russian Math School." This approach is named for its roots in the educational practices of the former Soviet Union and its satellite states. In the West, students typically learn arithmetic in a linear sequence: starting with addition and subtraction, followed by multiplication in the next grade, and then division. However, in countries like Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and other former Soviet Bloc nations, children begin learning algebra as early as first grade. They pick up basic arithmetic operations—addition, subtraction, and multiplication—along the way. By eighth grade, these students have a considerably advanced mathematical skill set. By the time they're in high school, they tackle complex mathematical concepts.

This rigorous education approach, stemming perhaps from the era of communism, ensured top-tier education standards in these countries. As a result, places like Russia or Belarus often produce exceptional developers and technical experts.

Cultural expectations also play a role in this educational emphasis. For instance, when I was considering college, my father was willing to support my tuition, but only if I pursued a degree in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics). When I expressed interest in finance, he made it clear he wouldn't fund that choice. This perspective on prioritising technical education isn't just a family preference; it's a widespread cultural sentiment.

I've noticed that a significant majority of Poles working abroad, especially in places like Silicon Valley, possess strong technical skills. During my interactions and research, I'd often come across open-source repositories on platforms like GitHub and Bitbucket. Strikingly, 15%-20% of the contributors had distinctly Polish-sounding surnames, ending in suffixes like CZ, Y, K, CZ, UK, SKI, and CHOOK. This prevalence only solidified my belief in the untapped potential of the Polish technical workforce on a global scale.

Chris: Lots of Z’s!

Dominik: Tons of, yeah, CZs as Zeds. And it's just that because the place has been, at least in my opinion, more or less isolated from the rest of the world for over half a century. You are now getting to a point where people are starting to realise that this isn't just some backwater former communist state with nothing to offer. Our most valuable resources are our people.

Chris: I think it's interesting when you look at the tech startups in Poland. I saw a figure the other day that 43% have females on the executive team and I think that's a representation not just in STEM, but in equality and diversity.

Dominik: About a year ago, I attended a conference in the UK with a Polish friend. It was a small, intimate gathering, and one of the discussions centered on increasing female representation in technical fields. When the topic came up, my friend mentioned that Poland already boasts a significant number of women in tech. The attendees were curious about how Poland achieved this, but my friend admitted that it's just always been that way. However, he shared a theory: after the war, many Polish women had to assume both traditional male and female roles within families out of necessity. This dual role has left a lasting impact on Polish culture. Even if a woman takes on a conventional role at home, she is often still the decision-maker, contrasting with some dynamics observed in American families. What surprised me most upon arriving here was seeing that nearly 35% of the engineering department was female.

Chris: I think there's two things that hold Poland back. One is that, when you look at American organisations, people are very confident, very sales oriented. In Poland, when it comes to selling and arrogance, there isn’t any. They Polish seem quite humble, so they don't sell well but, when they get a contract, the service is fantastic.

Dominik: Certainly, our historical experiences have deeply impacted our national psyche. Having been under occupation since the 18th century, many generations of Poles have grown up hearing tales of our nation's former independence. This history has engrained an inferiority complex into our cultural consciousness, which I believe remains prevalent today. A compelling book "It Didn't Start With You" delves into this phenomenon, highlighting how traumatic experiences can resonate through multiple generations. The author suggests that even descendants who didn't directly face these events might still be affected by them at a subconscious level.

When I first arrived in Poland, surrounded by people who shared my heritage, I recognised my own traits in their behavior. Two things stood out to me: Poles often display an 'inferiority complex,’ starkly contrasting the superiority complex observed in the French, who proudly champion their culture and products. Poles are typically reserved in promoting their own achievements, a mindset that clashes with the American ethos of robust self-advertisement excellence. Often, when I encourage my team to be more assertive in presenting our offerings, they urge moderation, reluctant to appear too boastful.

Moreover, there's also a noticeable 'scarcity complex' among Poles. This was evident when I observed founders juggling multiple ventures, possibly due to a fear that their primary venture might fail. This lack of focus, however, hinders excellence in any one endeavor.

My proposed solution is fostering communities of Polish Americans considering returning to Poland. By doing so, we can infuse some American optimism into the local mindset. If we surround ourselves only with those who share our entrenched beliefs, breaking free from this cycle becomes challenging. Introducing a dose of American optimism might be the catalyst for change, as optimism has a contagious nature, potentially teaching others to envision things differently.

Chris: I've been trying to work with some of the Polish companies to become international, global, and the challenge I've found that the management is often older. They've grown up in this humility in Poland for all of their years, and there hasn't been an international workforce integration into the country, so they don't understand international expansion. They're really challenged by it. How do we get that growth expansion view into the public organisation?

Dominik: Engaging with older managerial generations can be tough. I've faced such challenges throughout my professional journey. Often, their mindset is: "If there was a better way, I'd be doing it." That's why I gravitate towards startups, where innovative thinking is more prevalent. My peers and I, from my generation, tend to be more open-minded. Remarkably, the younger generation, the Zoomers in their early twenties and close to two decades younger than me, display even greater optimism.

As time progresses, mindsets naturally evolve. My current initiative is to bring back individuals who have spent substantial time abroad, hoping their diverse experiences might inject a fresh perspective and subtly influence the prevailing mindset. However, it's daunting. I tend to step back when I encounter middle management individuals who are set in their ways, resistant to new ideas. Finding a solution to this ingrained resistance remains elusive to me.

Chris: A final question is that I just saw a report this morning about the best place to have a tech startup in Europe, and Warsaw didn’t appear in the top 10. Why is that?

Dominik: Articles with political biases surface regularly. Observing local sentiment, it's clear that the current government isn't free from criticism. Yet, regardless of who's in charge, Poland remains Poland, with its unique challenges and history of governance. No government will ever achieve perfection or be entirely free from corruption. Personally, I would advocate for an overhaul, shedding inefficiencies. Some startup rankings may have political undertones, and detractors quickly highlight any omission of Poland from top lists.

As someone with an engineering mindset, I value data-driven insights. Data suggests Poland remains among the most cost-effective places to establish a business, especially when considering the quality of engineering talent available. Noteworthy is the influx of Western and U.S. businesses setting up in Poland. While cities like London and Paris boast commendable tech talent and educational infrastructure, statistical data reveals an impressive feat for Poland. Despite being the sixth most populous country in Europe, since 2013, it has produced the fourth-highest number of STEM graduates. This achievement is significant when compared to more populous countries like the UK, Germany, and France.

Some of these rankings can be influenced by PR campaigns backed by nations with deeper pockets, aiming to attract foreign investments. Unfortunately, Poland's promotional efforts lag behind. Whether this can be attributed to historical self-perceptions is open for discussion. That is why I’ve taken it upon myself to do the dirty work, and make it part of my public service to promote Poland’s potential.

Chris: It does because the country doesn't market itself properly. People don't realise that you've got fantastic resorts on the Hel peninsula. You've got skiing in the south in the winter. There's so many fantastic things here in the lakes. Tourism to Poland is not really a thing that's ever been on the agenda of anyone in Britain.

Dominik: Absolutely, there are so many hidden gems here. I'm currently in Katowice, where my wife's family lives. They also own a mountain house in Bieszczady near the Ukrainian border. It's a gorgeous place that even most Poles haven't explored. Plus, it remains affordable. Living in the US, especially in cities like Philadelphia, your travel options are limited to cities like New York, Boston, and maybe Miami or Dallas. But everything's so spread out. Places like Chicago exist, but many states are simply flown over, there’s a reason they’re called that.

In contrast, Poland offers a central location in Europe. This past July, my wife and I drove to Italy, then Switzerland, France, and back to Poland. The journey exposed us to rich cultures and languages at every turn. Americans, in general, might lack this appreciation for diverse cultures, often prioritising English above all other languages.

I used to be of the same mindset, but living here has expanded my horizons. It's beneficial to immerse oneself in different cultures and languages. In contrast, many US cities are facing challenges, from escalating homeless issues to drug problems. People, especially those of Polish descent, have been expressing their disillusionment with the US situation and showing interest in Poland. If the US doesn't address its challenges, I foresee more people considering a move to places like Poland.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...