I’ve been writing about the war on cash for years. It’s a constant theme that comes up at conferences like SIBOS, and the first time I think I heard the phrase was a Visa presentation back in the 2000s. Back in 2012, I wrote about a Pew report that surveyed a range of experts about mobile wallets in 2020.

A majority of respondents supported the scenario that by 2020 most people will have embraced and fully adopted the use of smart-device swiping for purchases they make, nearly eliminating the need for cash or credit cards.

Nope.

After all, the war on cash is created by banks as cash is inefficient. It is paper-based, has to have huge logistics about its movements between corporations, institutions and banks, and is a pain in the ass compared to a quick digital swipe … for the provider.

For the user, cash is pretty good. It is immediate, trusted and holds its value. More specifically, it is anonymous and can be passed between people with immediacy. That’s why users – people – don’t want to lose access to cash.

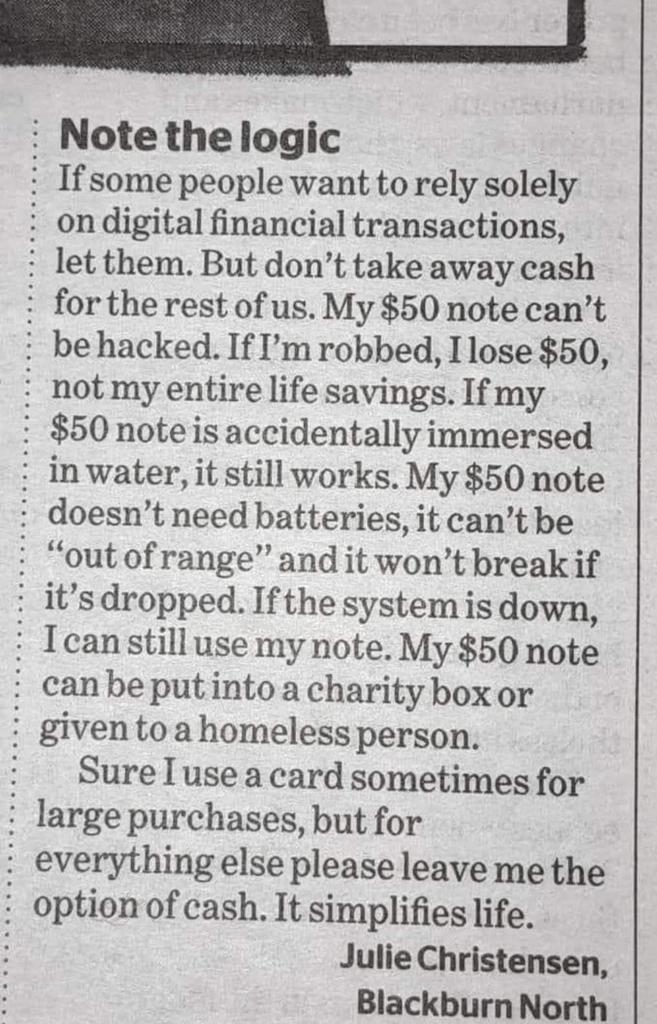

There are various stories about this, many appearing in my inbox in the last few weeks. For example, Julie from Blackburn sent a point of view to one of the national newspapers explaining why cash works best?

Her math is slightly out but, even so, you get the idea.

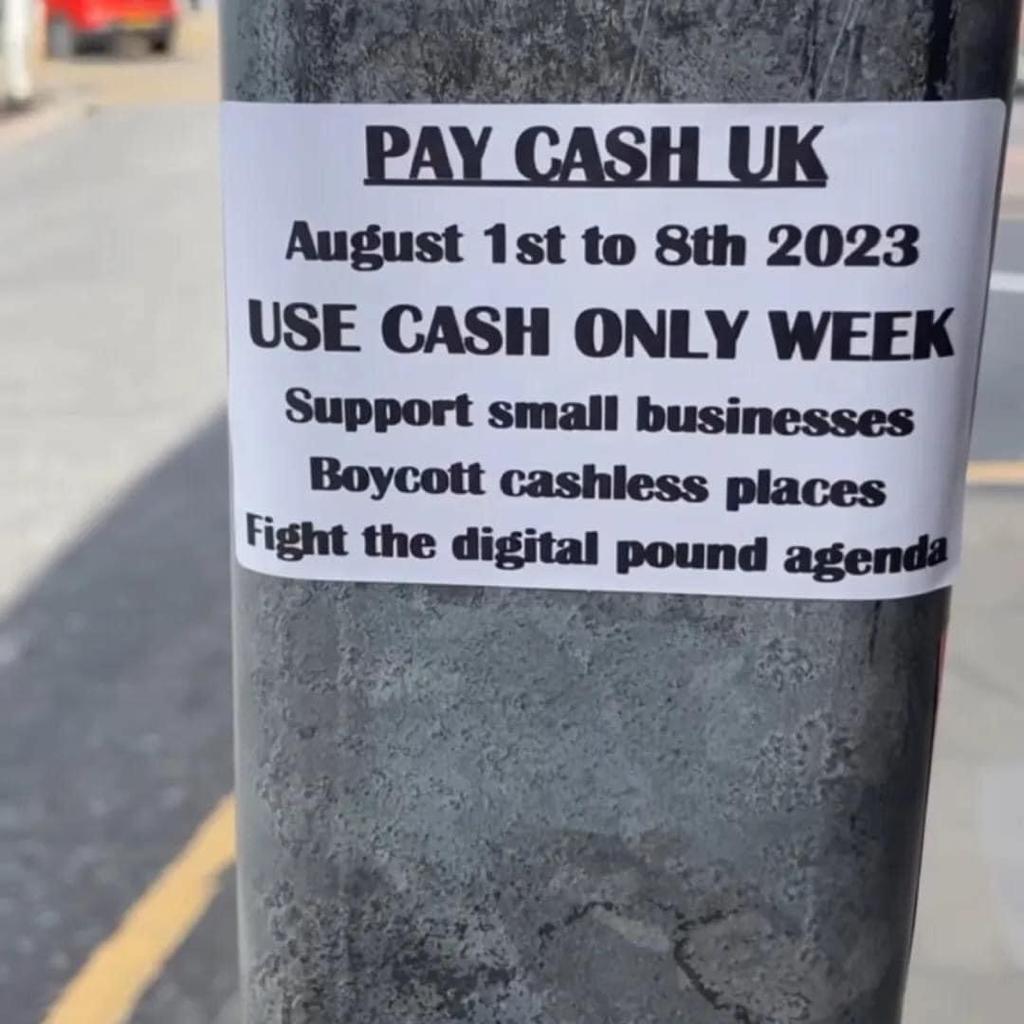

Then, whilst on a walkabout, I discovered that this week is being promoted as a national Cash Only Week.

It’s not been widely promoted – not a single news programme mentioned it – but it’s interested that consumers want to fight the digital pound agenda.

In fact, I then heard about a bank that tried to ban cash in their branches. They rolled out a test where only ATMs were available. No cash deposits or withdrawals allowed. During the three-month test, they had massive customer complaints and thousands of account closures. More importantly, staff did not support the idea and told customers that they should close their accounts if they were unhappy.

Unsurprisingly, the bank reversed the policy after the three-month test, and cash is still used wide and deep across the economy. I guess the question always comes back to: why? The answer is simple: there is no cash equivalent replacement.

This is articulated brilliantly by Brett Scott, who is described as “a campaigner, monetary anthropologist and former broker”.

In two lengthy recent updates, Brett breaks down why cash is the enemy of the state and the hero of the consumer. Here’s a quick summary of the key paragraphs and points made.

The Luddite's Guide to Defending Cash

The powers that be “say that digital automation - and the speed, scale and interconnection it brings - is not only good, but unstoppable. This ideology is nested in another, deeper, ideology, which says that the global economy must always expand and accelerate. With this vision as a backdrop, we’re encouraged to then engage in a series of digitization ‘races’ (like a ‘race to cashlessness’ or a ‘race to AI’). Ideally, you’re supposed to lead the way in these races by actively developing, pushing and embracing the technology, but if you have other priorities you’re told to prepare for the transition, and adapt.”

Brett then makes a key point about imagining if cash was converted to casino chips and then could not be converted back. Here, there are two key issues:

- Legal: If a casino refused to redeem my chips for cash, I’d sue them, but what if my bank closes down its branches and ATMs to stop me cashing out my digital chips? They are basically saying ‘you cannot exit our systems’, or alternatively ‘you have no right to exit our systems’

- Financial stability: An unredeemable casino chip is a dodgy casino chip. An unredeemable bank-issued ‘digital casino chip’, similarly, is an unstable and dodgy form of money, even if it gets moved around via a flashy and secure app. Ironically, as the public cash system is undermined, our confidence in the private digital systems risks being undermined too (incidentally, this stability concern is a major reason why governments are experimenting with ‘digital cash’ or CBDCs)

… even if you do believe cash is old, inefficient, and dangerous, it structurally underpins the digital systems that you think are so new, efficient and safe. Digital money is not an ‘upgrade’ to cash, because it derives its own power from cash. If you don’t believe that, watch what happens every time the banking sector looks shaky, or a crisis looms: cash withdrawals spike.

I particularly liked his commentary on the similarity between Uber and a bicycle (step 4 on his list).

Cash is the bicycle of payments (or mountainbike), while the bank-issued casino chips we use for digital payments are the Uber of payments.

In this context, there are unique characteristics that make cash and digital payments complementary, just as bicycles and Ubers are complementary. There are two specifically critical differences:

- Autonomy vs. Dependence: With a bicycle, I directly control it. With Uber, I’m relying on a third party. Similarly, with cash, I directly control it. With digital payments, I’m relying on a whole series of third parties.

- Public vs. Private: Bicycles only require public infrastructure, whereas Uber relies on a private corporate infrastructure that runs on top of public infrastructure. Similarly, cash is a public utility, whereas paying for things with digital casino chips involves becoming dependent on private corporate infrastructures (which, as we saw in the previous section, are built on top of the public money system)

As mentioned, Brett’s columns are lengthy, so I would recommend you read them if you want more.

Meantime, a final thought. If we move to CBDCs, should the central banks pay interest on cash? This point was raised by the former chief economist of the Bank of England, Andy Haldane, this week. In a column in the Financial Times, he claims that we are missing an opportunity to level the playing field of money in the interests of consumers.

“Cash is much more than a payments technology. It is one of the purest and oldest forms of public good, a symbol of identity and sovereignty. Choices about this public good are, ultimately and rightly, ones for citizens rather than central bankers or cryptographers. They are social, not technological, choices — and sometimes emotional ones.”

He continues, with a key point about seigniorage:

“Physical cash is an interest-free loan to government, a direct tax on citizens levied in proportion to their cash holdings at a tax rate given by the interest rate. Most people are blissfully unaware they are being taxed in this way. The name of this tax — seigniorage — adds to its mystery and oddity.

“The oddity does not end there. Seigniorage is a stealth tax that is both large and highly regressive. Highly regressive because cash is held disproportionately by the poorest and least advantaged in society. Large because, with a global stock of physical currency estimated at around $8.3tn among the world’s biggest economies, and interest rates of say 5 per cent, it amounts to a tax on global citizens of over $400bn each year.”

And concludes that CBDCs being designed as non-interest-bearing currencies is a key issue and oversight as, for citizens, they should have the benefits of CBDCs that provide returns rather than being the stealthy seigniorage tax that they look like continuing.

Anyways, after so many years, decades and maybe even centuries of debating the pros and cons of cash, I’m going to ignore it all and invest in bitcoin.

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...