I just watched Dumb Money, the true story of Gamestop where a wild band of small investors led by Roaring Kitty attacked the big Wall Street short sellers by banging the buck. The more small investors invested, via Robin Hood, the more short sellers lost as the stock rose instead of falling. It’s a good movie, particularly for fintech nerds like me, but there’s a moment in the movie where a seasoned veteran says there is no way the rebel troops will win as it’s all been tried before. He cited the case of Piggly Wiggly. What? Piggly Wiggly is an American supermarket chain with over 500 independently owned stores as of 2024.

But, a century ago, back in 1923, there was a rebellion against Wall Street that failed.

What happened?

Well, back in 1916, Piggly Wiggly was launched by Clarence Saunders as the first self-service supermarket store. Before then, you would give your shopping list to a store clerk, and they would get the items for you. Oh, how times have changed but, with the launch of Piggly Wiggly, American shopping changed forever too.

Here’s the story of what happened, summarised from this article on Slate:

A century before GameStop, Piggly Wiggly’s owner tried to stick it to Wall Street. (slate.com)

Piggly Wiggly founder Clarence Saunders came from a poor family in western Virginia. He cycled through a series of menial jobs until 1916, when, at the age of 35, he set up America’s first self-service grocery store in Memphis, Tennessee. He called it Piggy Wiggly, but no one really knows why. When asked how he came to choose the name, he would often answer: “So people like you can ask me that question.”

The recent volatility in the price of GameStop and other stocks has been characterized—rightly or wrongly—as an unprecedented populist revolt by small-time traders against big hedge funds. While the offensive by users of the Reddit forum WallStreetBets against the short positions of institutional traders made for a dramatic two weeks on Wall Street, the episode wasn’t the first, or even the most remarkable, David vs. Goliath battle to animate the stock exchange. Nearly a century before, in 1923, a Southern businessman named Clarence Saunders tried to orchestrate an epic short squeeze on well-pedigreed traders all by himself. The gambit was both spectacular and disastrous, ending when the New York Stock Exchange sided with short sellers and changed the rules on him. In a short span, Saunders—who would come to be known as “the boob from Tennessee”—went from being feted as the conqueror of Wall Street to being bankrupt and unemployed.

Saunders has largely been forgotten, but as described in Clarence Saunders and the Founding of Piggly Wiggly: The Rise and Fall of a Memphis Maverick by Mike Freeman, he was one of the great entrepreneurs of the 20th century. Short and stocky, with neatly parted hair, blue eyes, bushy eyebrows, and an impish smile, he came from a poor family in western Virginia. He cycled through a series of menial jobs until 1916, when, at the age of 35, he set up America’s first self-service grocery store in Memphis, Tennessee. He called it Piggy Wiggly, but no one really knows why. When asked how he came to choose the name, he would often answer: “So people like you can ask me that question.”

Within months of opening his first store, Saunders was already boasting that “it shall be said by all men [that] the Piggly Wigglies shall multiply and replenish the earth with more and cleaner things to eat.” Piggly Wiggly didn’t quite conquer the earth, but by 1922 it owned or franchised more than 1,200 stores throughout the United States, each painted in brown, blue, and yellow.

As Piggly Wiggly expanded, Saunders became rich and caught the attention of Wall Street, who listed its stock for trading in 1922. Due to uncertain times and the failure of other stocks, by the end of 1922 short sellers decided Piggly Wiggly was also vulnerable, although there was no proof of that idea. Nevertheless, they decided to short it, where you sell the stocks high to drive the price down, and buy the stock at the lowered price to make a tidy profit. Then you do the same again*.

Saunders was livid. He felt like Wall Street was swooping down on Piggly Wiggly “like an eagle on a chicken,” and decided that he would “break Wall Street” by buying Piggly Wiggly stock and driving the price back up. Next move, he borrowed $10 million and bought back half of the company’s shares within a week. By March 1923, Saunders controlled more than 198,000 shares, or 99 percent of all Piggly Wiggly stock, whose price had risen from $39 to $60 in six months and was continually going upwards, confounding the short sellers.

The thing is that Clarence was not a Wall Street insider. He was a country boy salesman who had created a great business, based on a good idea. The Wall Street insiders went to the controllers of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), where Piggly Wiggly stock traded, and complained.

Back in 1923, there was SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) and NYSE set its own rules for how stocks could be traded. Its governing committees were filled with Wall Street insiders. Once they learned that a country bumpkin was trying to corner the Piggly Wiggly market, they launched an investigation.

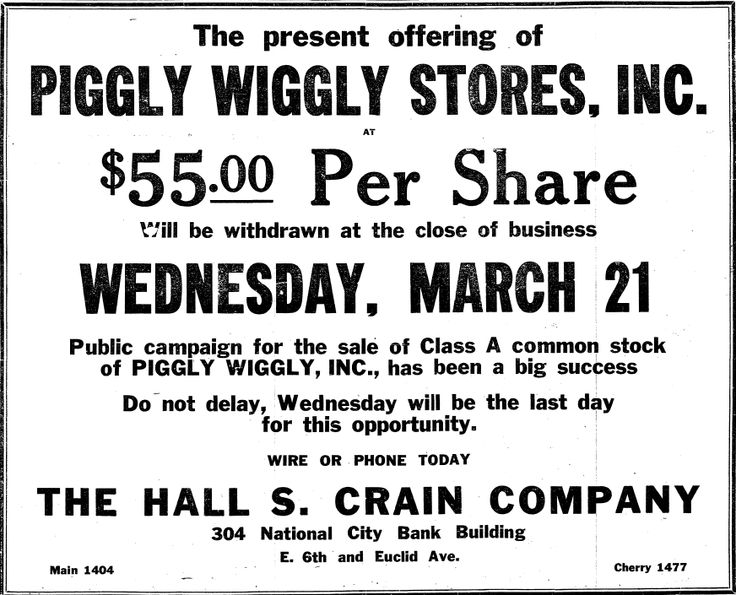

At the same time, Saunders realised that if he started selling any of his stock on the exchange, it would benefit the short sellers, so he decided to sell stocks directly to the public by taking out adverts in the newspapers and offering the stock sale at a discount.

This was kind of shorting the shorters, and the exchange in their own game by going direct.

On March 20, 1923, Saunders decided that his short squeeze was ready. While he had been buying Piggly Wiggly stock, he had also been allowing his brokers to lend those shares to short sellers. A lender can ask for his borrowed securities back at any time. That morning, Saunders called for the return of 42,000 shares that he had lent to short sellers. Under the rules of the New York Stock Exchange, the short sellers had 24 hours to comply. As short sellers scrambled to buy shares, the price of Piggly Wiggly rocketed from $75 to $124 in the first few hours of trading. Saunders had, it appeared, won a great victory over Wall Street. Like the hedge funds who had shorted GameStop, the traders short on Piggly Wiggly would have to buy shares at a price much higher than what they had sold them for. Throughout the country, Saunders was cheered on for slaying the short sellers.

VICTORY!!!

Ah, no. Hours after Piggly Wiggly reached its peak price, NYSE indefinitely suspended all trading of the stock. On March 22 1923, the exchange permanently barred Piggly Wiggly from being traded. The exchange also broke its own rules and extended the time for delivery of the short shares until the following week.

These actions caused the stock to fall, gave short sellers and banks breathing time and defeated Clarence Saunders. As he says it: “Wall Street got licked and called its ‘mamma’ and, of course, ‘mamma’ heard the cry of her petted child.”

Saunders was left with $5 million in debt and 100,000 shares of his company that he couldn’t sell.

In August 1923, with payments due imminently on his loans, Saunders resigned as president of Piggly Wiggly and relinquished all his property—his stock, his cars, even the Pink Palace—to his creditors. Some of his shares were subsequently auctioned for $1. A year later, he filed for bankruptcy.

To Saunders’ credit, he rebounded from this stinging defeat, as Mike Freeman describes in his biography. Soon after his bankruptcy, he started another grocery chain called “Clarence Saunders, Sole Owner of My Name Stores.” Despite the odd name, this chain was successful enough that it made Saunders a millionaire again.

For this and other good stories about trading and Wall Street, it’s worth picking up a copy of Business Adventures: Twelve Classic Tales From the World of Wall Street.

Meanwhile, what happened to Gamestop and Roaring Kitty? Watch the film to find out.

* This is what happened with Gamestop, but every time the shorters were selling, the Robin Hood crew were buying

** Institutional investors, hedge funds, banks and mutual fund companies are labelled “smart money”, while retail (individual) investors are called “dumb money”

Chris M Skinner

Chris Skinner is best known as an independent commentator on the financial markets through his blog, TheFinanser.com, as author of the bestselling book Digital Bank, and Chair of the European networking forum the Financial Services Club. He has been voted one of the most influential people in banking by The Financial Brand (as well as one of the best blogs), a FinTech Titan (Next Bank), one of the Fintech Leaders you need to follow (City AM, Deluxe and Jax Finance), as well as one of the Top 40 most influential people in financial technology by the Wall Street Journal's Financial News. To learn more click here...